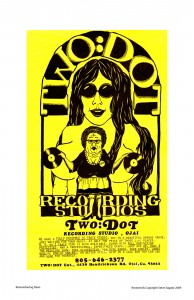

Groovy History: Ojai’s Two:Dot Studio recorded the sounds of the psychedelic ’60s. Now it’s playback time. by Mark Lewis

When Dean and JoAnne Thompson built themselves a home in the East End back in 1954, they made the news with their choice of material. Rather than put up a standard suburban ranch house, they hired a contractor to mix mud and straw into large blocks, bake them in the sun and truck them to an isolated lot near the end of Hendrickson Road. There, the blocks were assembled into a handsome, Mission-style ranch house, complete with a two-car garage and a workshop for Dean to putter around in.

“We went back to the good old Chumash construction and built an adobe house,” JoAnne recalls. “Warm in the winter, cool in the summer.”

The Ojai Valley News considered this structure so unusual that they ran a story about its construction. But after that auspicious debut, the house subsided into anonymity. No one took much notice, a few years later, when Dean converted his workshop and part of the garage into a homemade recording studio. The Thompsons raised three sons in the house, then sold it in 1976 and moved to Santa Barbara. In 1983 the house passed into the possession of its current owners: Darrell Jones, an engineer, and Glenda Jones, a painter who taught at Topa Topa Elementary School. The Joneses knew nothing of the house’s history. Then one day their friend Dennis Shives brought over an old record album, Milton Kelley’s “Home Brew,” and told them it had been recorded in their garage.

“I told them that they have got some big ghosts in this place,” Shives recalls. “That this is a magic place.”

Shives these days is an artist, but in 1970 he was primarily a musician, and he had played harmonica on the Kelley album. The best players in town regularly found their way to the Thompsons’ Two:Dot Recording Studio to cut their teeth as recording artists. Alas, none of the records they made there became hits. The little studio closed its doors when the Thompsons moved to Santa Barbara, and over the years it faded into oblivion — until the advent of the Internet, where time stands still, and nothing is lost forever.

These days, a copy of “Home Brew” that’s still in decent shape will go for hundreds of dollars on eBay — and a sealed, never-played copy might fetch $3,500. And “Home Brew” is not even the most sought-after Two:Dot recording. The long-vanished studio is barely remembered in Ojai, but it’s now world famous among collectors of obscure rock albums from the ’60s and early ’70s. Cultish websites make gushing references to the “legendary” Two:Dot, that mythical place where “mega-rare” albums like “Hendrickson Road House” were created. Enthusiasts in Europe and Japan will offer big bucks for vinyl rarities recorded in that converted garage — albums hardly anyone bought when they first came out. As long as a record can plausibly be categorized as “psych” or “psych-folk” — short for “psychedelic folk rock” — people will line up to bid for it.

This is the story of Two:Dot’s heyday, and its unlikely afterlife as a holy grail for record collectors. It’s set against the background of Ojai’s extraordinarily vibrant music scene during the Two:Dot era, which largely overlapped the psychedelic ’60s era. This was a time when several big-time rock stars came to Ojai and mixed easily with little-known local players, some of who would go on to bigger and better things. Two:Dot was a vital component of that scene. There were plenty of bars and clubs in the valley where bands could play live sets, but there was only one place in town to cut a record: Dean Thompson’s funky little adobe-walled studio in the middle of an orange grove, near the end of Hendrickson Road.

SOUND AND VISION

Dean and JoAnne first met at the University of Redlands around 1950. She was a voice major; he was a physics major with a minor in math. Together, they added up to something. By 1951 they had married and settled on Drown Street in Ojai, where Dean started work that September as the science teacher at Nordhoff High School. Five years later, Dean left Nordhoff to work for a neighbor, Lee Appleman, who had started an electronics business called Topatron. By then, the Thompsons had built their adobe house on Hendrickson Road, a private road that runs east from McNell Road to the top of a hill offering splendid views of Sulphur Mountain. Their three sons, Kenneth, Bryan and David, attended the nearby Monica Ros School. Their neighbors included the movie star Anthony Quinn.

The Thompsons planted 700 Valencia orange trees on their five-acre lot. (JoAnne planted the first 50 herself, by hand.) Meanwhile, Dean began to dabble in audio recording as a hobby. “He hung a microphone from the rafters in the living room and recorded me singing some Broadway tune,” JoAnne recalls. “Just for fun.”

In the late ’50s, Appleman moved Topatron to Garden Grove. Dean soon tired of the long commute. He decided to stay in Ojai and turn his recording hobby into a full-time career. For the name of his new venture, he reached back to his college days, when he and his friend Tom Oglesby had talked about starting a business someday and calling it Two:Dot, for their initials: Tom W. Oglesby and Dean O. Thompson. Years later, Dean revived the name for his Ojai recording studio. It appealed to his quirky sense of humor.

JoAnne handled the office duties, and Dean was the engineer. They did not initially set out to record rock ‘n’ roll acts. Two:Dot’s bread and butter was souvenir albums for church choirs, student chorales (including Nordhoff’s Gold ‘n’ Blue Singers) and high school musicals. (One album still in JoAnne’s collection is a Santa Barbara Youth Theatre production of “West Side Story” featuring Eduardo Villa, who currently makes his living as a tenor at New York’s Metropolitan Opera.) But in the mid ’60s, with the advent of the Beatles, the market for rock music grew exponentially. Suddenly, newly formed groups were crawling out of the woodwork, and they all dreamed of signing a record deal with a major label. These groups represented a potential bonanza for Two:Dot — and for Dean’s new friend Tom Lubin.

Lubin was a Santa Barbara City College student, a part-time radio DJ and a would-be music mogul, affiliated with a fledgling Santa Barbara label called Jet Set International. He already had produced a single by a local band called the Calliope, which had received some regional airplay and sold a few thousand copies. Now, Lubin was looking for a place to record Jet Set’s other acts, the folk singer Don Robertson and a garage-rock band called Blue Wood. But Jet Set was a shoestring operation, and studio time in L.A. was expensive. Somewhere, possibly at the radio station, Lubin heard about a little studio in Ojai with a decent 4-track tape recorder and reasonable rates.

“I think it was mid 1966,” Lubin says. “I ended up driving over Casitas Pass for the first time to see the Two:Dot studio. Over that year I’d drive that road countless times. Through farmland to Ojai to Hendrickson Road and more farmland. Hendrickson Road was one of those country roads that started out paved but quickly became dirt. Dean’s place was the end of the road. For those who belted up that road and missed Dean’s access drive, they would suddenly end up in a gully in the middle of Dean’s orange grove.”

The studio looked primitive, but it was fully functional, and the price was right. Lubin produced a Blue Wood single (“Turn Around” backed with “Happy Jack Mine”) and a Don Robertson album, “Yesterdays Rain” (sic). Neither record took off, but there were plenty of other musicians in the region who were eager to take their shot at success. Dean decided to place a bet on the rock ‘n’ roll boom.

“A few weeks later he called and said he was getting one of the new Ampex 8-track, 1-inch recorders which had just been introduced,” Lubin says. “We drove down to Audio Industries, which was the premier pro audio supplier in Hollywood. There we were on La Brea across from the old Chaplin studio that had just become A&M Studios, lifting the 8-track up into Dean’s old pickup. It took four of us, and it was seriously top-heavy.”

Dean’s new 8-track machine was more advanced than the one the Beatles had recently used in EMI’s Abbey Road studios in London while recording “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.”

“How proud he was to take it home to his studio in the middle of an orange field,” Lubin says. “Even the Beatles only had 4-track.”

Dean’s next move was to have Lubin record a demo album, to show what Two:Dot and its 8-track could do. Lubin recruited some musician friends from L.A., and they set to work writing songs.

It was now late July of 1967, the midway point of the Summer of Love. “Sgt. Pepper” was dominating the airwaves, and flower power was in full bloom. In downtown Ojai, hundreds of hippies spent that summer cavorting in the park, where they clashed with local rednecks, sometimes violently. But all was peaceful out on Hendrickson Road. Lubin and his friends commuted to Ojai every Friday evening and spent the weekend in the studio laying down tracks.

They called themselves Prufrock. By year’s end they had completed an impressive-sounding album that echoed all the psychedelic sounds emanating from San Francisco and Los Angeles. Then they disbanded and went their separate ways. Two:Dot never pressed any vinyl copies of the Prufrock record — it existed only on acetate. But it had served its intended purpose, by showing what an ambitious band could achieve at Two:Dot.

“The album pushed the little studio to the limit,” Lubin says. “I borrowed a harpsichord and a celeste from the UCSB Music Department. I organized a string section, found an arranger, got a brass section, a choir, found an extraordinary lead guitarist. We didn’t think it would ever get done, but of course it did. It was an impressive recording for Dean to use for demonstration.”

Installing the 8-track did not automatically vault Two:Dot into the big time. The Thompsons’ approach to marketing leaned heavily on word of mouth, so it took a while to build a regional reputation.

“We didn’t do any advertising,” JoAnne says. “We were just sort of open to whoever came. Some of them were pretty bad.”

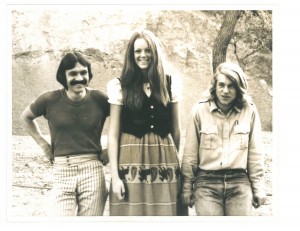

Others were undeniably talented. There was for example Dennis Shives, who played harmonica on Ronny Bowdon’s 1968 EP “Portrait of a Gambler,” recorded on Hendrickson Road. Another Two:Dot discovery was Ojai guitar whiz Martin Young, who was only 16 in 1969 when he recorded an album called “Take One” with local singer Sally Magill. Young played most of the instruments himself.

Two:Dot was not a full-fledged label; it was more akin to a vanity press. Dean generally ordered only as many album copies as the recording artist was willing to pay for. “The majority of the people who came to us used to sell them to their friends,” JoAnne says.

Some Two:Dot clients were more ambitious — they hoped to use their albums as demos to market themselves to major labels. Many of these demo albums were recorded with local musicians serving as session players. Dean paid these musicians with free studio time, which they could devote to their own projects. For homegrown Ojai players like Martin Young and his fellow guitar virtuoso Raj Rathor, Two:Dot’s unlikely presence in their tiny little town was an enormous stroke of luck.

“We were honing our craft there,” Rathor says. “What better place than a recording studio? It’s amazing that we had one.”

“It was our introduction to the professional-musician world,” Young says. “And Dean was just a gracious guy. A gentle soul.”

HOME BREW

Dean had no shortage of session players to call upon, because Ojai by the late ’60s had developed a thriving music scene. The homegrown talent was augmented by L.A. transplants like John Orvis, who moved up here from Venice in 1969. Orvis would strap a Pignose battery-powered amplifier on his back, plug in his left-handed guitar, and wander around the Arcade, serenading passersby with tasty blues licks. Nor was Orvis the only live-music option in town.

“You could go hear live music at six or seven places on a Friday night,” Shives recalls. He played harmonica with the Ojai All-Stars, which had a regular gig at the Ojai Club, a rowdy downtown bar located where Ojai Pizza is today. “There was also the Oaks, the Cactus Club, the Sand Dollar, the bowling alley, the Firebird, the Deer Lodge and the Wheel — all had live music,” Shives says.

Libbey Bowl was another popular venue for local musicians. It was there, early in the summer of 1970, that Dean Thompson met Milton Kelley.

Kelley was a singer-songwriter who had grown up in Ojai and was now back in town after serving a tour in Vietnam. He was part of the musical line-up at the bowl that day, and Dean liked what he heard.

“Dean was there recording some live stuff,” Kelley says. “He came up and said, ‘Hey, man, I’ve got a recording studio up on the hill. You should come up and do an album.’ ”

The result of that conversation was “Milton Kelley’s Home Brew,” released on the Two:Dot label. The backing musicians included Martin Young on guitar, Poi Purl on “jangle piano,” Ronny Bowdon on “bongo-congas” and Dennis Shives on harmonica. Dean was the engineer and the genial host.

“He knew what people needed to get them going,” Shives says. “You could feel comfortable up there. And when you feel comfortable, the music sounds better.”

Kelley’s friend Dan Cole had some recording experience — he had played drums for the Raiders, an early ’60s Ojai group that had once cut a single in a Hollywood studio. Cole ended up producing Kelley’s album.

“I listened to a bunch of his songs and we picked, like, 13 of them,” Cole says.

After they had recorded them all, Dean said they needed one more song to complete the album. On the spot, Kelley and Shives came up with “Peyote Pete.”

“We did it in one take,” Cole says. “And that’s the song everybody likes.”

“We printed 400 LPs and sold every one,” Kelley says.

Meanwhile, Dean was back in the studio recording another promising singer-songwriter, 19-year-old Sue Akins. She had grown up in Ventura but left home at 17, venturing north to Haight-Ashbury, the hippie mecca in San Francisco, before returning to Ventura County. By 1968 she had landed in Ojai, where she was living in the Cottages Among the Flowers on West Aliso Street, and working as a dishwasher at the Gables.

She had written a couple of songs that had impressed her friend and neighbor Phil Wilson, with whom she played music occasionally. As it happens, Wilson also played bass with a local trio, which had arranged to cut an audition tape at Two:Dot. During that recording session, Phil told Dean Thompson about his talented friend Sue, the teen-age troubadour who might be the next Laura Nyro.

“Eventually Dean asked to meet me, so I went up to the studio with Phil,” recalls Sue Randall (as she is now known). “I was a polite young lady of few words but I remember Dean’s beaming face and that jolly beard. I didn’t feel intimidated at all.”

Dean offered to produce an album for Randall.

“I’m sure I said something like, ‘Far out, man,’ ” she says. “Suddenly I had a whole lot of songwriting to do. And I kept my day job.”

The backing musicians for these sessions included Wilson on bass, Norman Lowe on guitar and Don Mendro on piano and drums.

“At first we recorded tracks with the group, whichever group was on board,” Randall says. “Later, Dean and I would do the solo material, songs I wrote for guitar and piano, autoharp and multiple voices. This is where Dean and I came together. Dean owned the candy store and he was letting me run through it, hog-wild, tasting all the wares, letting me use whatever I wanted.

“On some tracks, I would think we must be done, but Dean would say, ‘I think one more track would make it perfect, can you think of something?’ I could come up with new stuff at the drop of a hat. He was able to see this, though I couldn’t. I’m sure he was like this with all the musicians who came to his studio. Somehow, he knew how I wanted my song to sound and he made it happen.”

The album, “Hendrickson Road House,” came out in December 1970. Randall cannot recall exactly how many copies were pressed, but she thinks it was probably 200. She formed a group called Hendrickson Road House, with Phil Wilson on bass and Martin Young on guitar, and they promoted the album at their shows. Eventually the last copy was distributed, and no more were ever pressed.

COSMIC COWBOYS

As the ’60s turned into the ’70s, country rock began to supplant psychedelic rock, as musicians exchanged their Nehru jackets for fringed buckskin vests. Yet the early ’70s still counts as part of “the Sixties” — the era rather than the decade. The “cosmic cowboy” phase of the Sixties had kicked in, with Laurel Canyon as its epicenter. The music business was still booming, especially in Hollywood, where A&R men, the gatekeepers, reigned supreme. At the other end of the industry food chain, Two:Dot continued to record anyone who could pay for a session, and a few who couldn’t.

“Dean was always generous with the personal as well as his studio time,” Tom Lubin says. “Lots of acts didn’t pay for the time, or would do so sometime later if the recordings made any money. Some did. Dean did a lot of horse trading and bartering for painting, wiring, equipment, etc. I don’t know if he accepted eggs for studio time, but he probably did if he believed in the artist.”

Daniel Protheroe, who had played bass with the Calliope, did some session work at Two:Dot from time to time. One day, he asked Dean for a full-time staff job. Dean hired him and immediately left town on vacation, leaving Protheroe in charge of recording a single called “Love is an Animal,” by a man from the Santa Ynez area who owned a menagerie. Clients like this were strictly small-time, but Two:Dot seemed poised for bigger things. Especially when several prominent television actors who lived in the valley began coming to the studio to cut demos.

One was the actor and country singer Sheb Wooley, of “Rawhide” fame, who had topped the pop charts in 1958 with his novelty hit “The Purple People Eater.” Another was James Brolin of “Marcus Welby, M.D.” Then there was Michael Parks, the star of “Then Came Bronson,” who was living on Foothill Road. Parks was also a singer, and he was scheduled to do an album for Warner Bros. He decided to record it on Hendrickson Road. It was to be produced by another Ojai resident of the time, the folk-rock pioneer Jim Hendricks. With this big-time project in view, Dean decided to splurge on another studio expansion.

“So we ordered a 16-track tape recorder, and away we went,” Protheroe says.

Unfortunately, the Parks-Hendricks project fizzled. Protheroe did record some demos with Hendricks and the legendary songwriter and producer Van Dyke Parks (with Martin Young on guitar), but those sessions never resulted in an album. Still, the new 16-track machine did enhance Two:Dot’s regional reputation.

“Dean Thompson was widely known in the Central Coast,” says former Two:Dot technician Jeff Hanson. The studio “was a little dynamo out in the back woods that really made its mark.”

As word got around about Two:Dot’s high quality and low prices, clients from distant places began to beat a path to Dean’s door. “We had an Englishman come out,” Hanson says. “John Jones, a Brit. He found us.” Jones recorded his material, paid in cash for the sessions, took his tapes and left. “We never saw him again.”

Another unknown singer who recorded at Two:Dot in those days was Eddie Mahoney, who fronted a Berkeley rock group called the Rockets. Mahoney’s Two:Dot connection was Tom Lubin, who by this point was working for CBS Records in San Francisco. Lubin had taken on the Rockets as a personal project.

“I liked them, we got along, and so I arranged to produce and engineer four songs at Two:Dot,” he says. “The band and I went to Ojai a few times. Two:Dot was bigger now and there was a lot more gear. The old studio was now the control room, and the other half of the garage was now the studio.”

Pleased with the results of these sessions, Lubin took the tapes to his colleagues at CBS. To his chagrin, they declined to sign the Rockets, and the band soon broke up. But Eddie Mahoney did not disappear into obscurity.

“Eddie took the tapes to Bill Graham, changed his name to Eddie Money, and a couple of years later was signed to CBS,” Lubin says.

As Eddie Money, the singer would score big hits like “Baby Hold On” and “Take Me Home Tonight.” But in 1972 he was just another unknown rock ‘n’ roller who trekked to the Ojai boondocks to make a demo, hoping it would be his ticket to the big time. There were many more like him. Two:Dot continued to record church choirs, student chorales and school musicals, but it was the would-be rock stars who really kept things humming at the studio during the early to mid ’70s.

“We were cranking out a lot of work in those days,” Hanson says.

“It was mostly local bands,” the former Two:Dot engineer Larold Rebhun says. “We could do an album in a day.”

SAND DOLLAR DAYS (AND NIGHTS)

One of those local bands was the Country Z Men, whose lead vocalist, Alan Thornhill, had moved to Ojai in 1973. Other Z Men included Martin Young and Jim Monahan, with George Hawkins on bass and Todd Nelson on drums. The group did session work at Two:Dot and cut some demos of their own. “We never released any of it,” Thornhill says.

The Z Men had a steady gig playing at the Sand Dollar on East Ojai Avenue. (Formerly known as Boots and Saddles, it later changed its name to the Topa Topa Club, and is now a Chinese restaurant called the Golden Moon.)

“We played there six nights a week, and that place was full every night,” Thornhill says.

The Ojai scene was still going strong, and not just at the Sand Dollar. Glenda Jones, who was living in Ventura at the time, remembers driving up Highway 33 to hear live music at the Oaks, in its pre-spa phase.

“Everybody in the county used to come up and dance at the Oaks,” she says.

People came to Ojai from beyond the county, too. Famous people. John Lennon and Yoko Ono rented a house in the East End for several weeks in June 1972. They mostly kept to themselves, but other rock stars were more sociable. The singer Chaka Khan rented the old farmhouse on Persimmon Hill, where she threw epic parties. “They would go on for days,” Glenda Jones says. “You’d find people sleeping under trees.”

Ojai in this period resembled a northern outpost of Laurel Canyon. At least one full-fledged rock star of the era became a full-time resident: Jimmy Messina, who in 1972 bought himself a ranch on Creek Road. His musical partner Kenny Loggins was a frequent Ojai visitor who for awhile maintained a pied a terre in the old motor court on Mallory Way. Loggins in particular was willing to befriend the local musicians and hang out with them. He would come to the Sand Dollar to see the Country Z Men, and sometimes join them on stage.

“He sat in with us a couple of times,” Thornhill says.

“Of course we were all awe-struck,” Young says. “We recorded a couple of demos with Kenny.”

Naturally, those demos were cut at Two:Dot, still the only recording studio in town. Loggins & Messina did not cut any tracks there as a band — they recorded at Messina’s ranch, using a remote truck they brought up from Hollywood. But the two stars did visit Two:Dot together from time to time to check their mixes on Dean’s equipment.

Another Two:Dot visitor and Sand Dollar regular was a strikingly beautiful Ojai Valley School student named Rae Dawn Chong, the future film actress (and the daughter of Tommy Chong of “Cheech and Chong” fame).

“I met Kenny and Jim on the corner in the center of town when I was 12,” Chong says. “They were cute guys, obviously older, but we started talking and they invited me to lunch and we became friends instantly. They took me up to Messina’s ranch where they were recording that day.”

Messina’s wife initially was nonplussed by Chong’s presence: “She was very cautious and angry at first, me being jailbait, but realized I had charmed them into adopting me in a platonic way, so she relaxed and made sure I was safely returned back at school.”

Chong was a big fan of the Country Z Men.

“My home economics teacher was dating Martin Young,” she says. “Her name was Vanessa Hendricks. [Jim Hendricks’s ex.] She was my pal and she took me to the Sand Dollar to see them. I went quite a bit because I spent my weekends with her.”

Chong also made the scene at Two:Dot, at least when the Z Men were in session.

“I loved the band. I think Alan Thornhill is an amazing singer. George Hawkins was my first big crush. I thankfully grew out of that but my teens were filled with awesome music made by dear friends. I felt very lucky to be so exposed to it.”

Hawkins left the Z Men in 1976 to join Loggins & Messina on their farewell tour. “His life changed overnight,” Larold Rebhun recalls, as Hawkins went on to play bass with a long list of hall-of-fame rock stars over the years.

Rebhun’s life changed too, if not quite overnight: The Two:Dot technician started working in that remote truck at Messina’s ranch, which led eventually to an illustrious career as a engineer at Cherokee Studios in Hollywood. (Rebhun later moved into TV and film work, and in 2011 he won an Emmy for sound recording.)

Ojai’s Loggins & Messina era also was pivotal for Alan Thornhill, who co-wrote a song with Kenny Loggins and Martin Young, and made connections that led to some big-time gigs, such playing guitar in Hoyt Axton’s band. Young went on to play in Clint Black’s band for many years. The Country Z Men never released a record as a group, but they went on to successful individual careers, helped along the way to some degree by connections originally made through Kenny Loggins and Jim Messina.

“It was really a big thing for us,” Thornhill says.

It was less of a big thing for Dean Thompson, since Loggins & Messina as a group never recorded anything in his studio. But in 1974, another well-known rock group did come to Hendrickson Road to cut an album. And these sessions would yield the only hit song ever recorded at Two:Dot.

TOP OF THE POPS

Dr. Hook and the Medicine Show had scored big hits in 1972 with “Sylvia’s Mother” and “The Cover of the Rolling Stone.” But their follow-up singles all flopped, and two years later they were broke.

“We recorded a lot of the ‘Bankrupt’ album in Ojai, including the hit single ‘Only 16,’ which was a cover of the old Sam Cooke song,” says the former Dr. Hook vocalist Dennis Locorriere.

“I don’t remember who found the studio or how we came to record there,” Locorriere says. “As the album title boldly states, we were broke and didn’t have a record deal, so it was probably less expensive to do the recording there than at a big, fancy studio in one of the major cities. I don’t remember much about the studio itself because we were touring and would drop in on days off to do some work on the tracks and get right back on the road.”

“Bankrupt” came out on Capitol Records in 1975, and “Only 16” topped out at No. 6 on the Billboard singles charts in January 1976, with Locorriere on lead vocal. Two:Dot finally had produced an actual hit: “Only 16” soon was certified as a gold record. But already the little studio’s days were numbered.

By this point, the trippy ’60s era finally had expired, and “the Seventies” were in full swing. Rock music was now a serious business, and there was a limit to what Dean and JoAnne Thompson could accomplish in a converted garage in a tiny town in the middle of nowhere. They decided to move to a bigger market and open a much bigger recording studio. In March 1976, they sold the house on Hendrickson Road and moved to Santa Barbara.

Alan Thornhill remembers ferrying boxes of Two:Dot equipment to Santa Barbara in his old VW van, driving over Casitas Pass during a heavy rainstorm. Dean’s new building was an old Salvation Army gymnasium with a leaky roof. As Thornhill unloaded his van there and looked around, he was not very impressed. “I remember thinking, ‘This is going to be the new studio?’ But it turned out great.”

Dean retired the Two:Dot name and dubbed the new studio Santa Barbara Sound. He built a first-class facility that attracted world-famous clients, as Thornhill discovered one evening when he dropped by and found himself keeping company with Ringo Starr. (They watched TV together while Joe Walsh mixed Ringo’s latest album on Dean’s shiny new 24-track machine.)

“Dean slowed down a bit in Santa Barbara,” Lubin says. “Once the studio was Santa Barbara Sound it was world class, but also more of a business, and I think not so much fun for Dean.”

Dennis Shives makes a similar point: The Santa Barbara operation was vastly bigger and better than Two:Dot had been, but perhaps less satisfying to run.

“At that point it was not the same,” says Shives. “It reminded me of Los Angeles.”

By 1990, Dean had sold Santa Barbara Sound and gone on to other things. He died in 1996, at the age of 70. The old Two:Dot crowd was well represented at his memorial service.

“It was one of those funerals that take forever, because everybody had something to say,” Shives says. “Great stories!”

TWO:DOT REDUX

Dean Thompson’s professional legacy endures, as reflected in the subsequent careers of his former technicians, many of who now run their own studios or audio-related businesses. “Dean was a real mentor,” Protheroe says. “He touched a lot of lives.”

But Two:Dot’s physical legacy — the actual recordings — seemed destined for the scrapheap. In fact, that’s precisely where many of them ended up. Some years after the move to Santa Barbara, Dean made a good-faith effort to locate everyone who had ever recorded anything on Hendrickson Road. The people he was able to locate were offered the master tapes of their sessions.

“The others eventually were tossed,” JoAnne says.

So that was that. Except that it wasn’t. Even before Dean died, old Two:Dot albums were popping up in unexpected places, especially in the record collections of people who were fascinated by late ’60s psychedelia. One such collector was Raymond Dumont, who lives in Buchs, an Ojai-sized town near Zurich in Switzerland.

Dumont makes a specialty of reissuing obscure late ’60s albums on vinyl through his own label, RD Records. In the early ’90s, he was particularly interested in an extremely rare and much-sought-after recording by a singer named Arthur, last name unknown. This Arthur apparently had recorded his one-sided LP at a label called Two:Dot in 1969. But no one had ever heard of Two:Dot. Eventually, Dumont’s research led him to Dean Thompson. He placed an overseas call to Santa Barbara.

“But Dean did not remember Arthur,” Dumont says.

Some time later, Dumont called again to ask more questions, only to find that Dean had died, and that JoAnne did not remember Arthur either.

With further research, Dumont eventually determined that the mysterious Arthur was a Canadian singer-songwriter named Arthur Gee, who had cut that Two:Dot record as a demo. Gee then went on to record two albums in the early 1970s for Denver-based Tumbleweeds Records. Neither one made a splash, so Gee returned to Canada, where Dumont eventually found him many years later. With Gee’s cooperation, Dumont produced a handsomely mounted vinyl reissue of the “Arthur” Two:Dot sessions, now titled “In Search Of.”

The fuss over the Arthur album rescued Two:Dot from obscurity. Soon, the collectors of late ’60s “psych-folk” records had a new holy grail to pursue: Sue Akins’s “Hendrickson Road House.”

“It’s a great record,” says Dumont, who tried in vain to find Akins so he could reissue her album too. But Akins now had a different name, Sue Randall, and she had left the music business behind many years before. She was difficult to locate, and completely unaware of the renewed interest in her old album.

“I never found her,” Dumont says.

Meanwhile, original copies of “Hendrickson Road House” were going for $1,000 or more on eBay. Collectors began bidding for anything with a Two:Dot label, on the theory that it would have a similar sound to the Arthur and Akins albums. In Ojai, an astonished Milton Kelley was informed that a pristine copy of “Home Brew” was now worth its weight in gold, and then some. (Alas, Kelley was not in a position to cash in. He has only one copy left, and it’s been played a lot.)

Three factors drove the collectors’ fascination with Two:Dot. First, scarcity. Two:Dot generally printed albums in tiny lots: 50 copies, 100 copies, perhaps 200 copies. Four decades later, how many could possibly be left?

Second, sound quality. For a tiny studio out in the boondocks, Two:Dot maintained very high technical standards. And Two:Dot of course used analog equipment, which later was rendered obsolete by the digital revolution. Many audiophiles nowadays revile the sound of digital recordings and thrill to the sound of a well-made analog album, including those cut at Two:Dot.

Third, the cultural context. If a record gives off the right vibe, redolent of the late ’60s, then it will be cherished as an endearing artifact of that tie-dyed, paisley-patterned period that began with “Sgt. Pepper.”

“The late ’60s, early ’70s psych stuff is very interesting to collectors,” Dumont says. “Especially when it was released locally.”

The problem for collectors is that most Two:Dot albums were not in fact very psychedelic. Many a psych-folk aficionado has ponied up for a rare Two:Dot title by the likes of the Guys and Dolls or Mountain Glory, only to find himself in possession of a mediocre country-rock album, or one with a Christian theme. Even more problematic is “Maybe,” a very rare Two:Dot album by the groovy-sounding Mystic Zephyrs 4. Collectors who shell out hundreds of dollars for a copy may be disappointed to learn that the Zephyrs in question were four squeaky-clean teenage siblings from Ventura, whose album is rather less trippy than advertised. Back it goes on the online auction market with a new and somewhat desperate sales pitch, such as this one (actual ad):

“Incredibly strange and rare original private press from 1974! Incompetent teen-age family band with sincere pop songs and positive vibes. The drummer is only 12! May be your only chance to grab this highly sought after and mega-rare artifact!”

Eventually, Two:Dot collectors unearthed the rarest artifact of all: The original Prufrock demo album from 1967, of which only six acetate copies were ever made. Somehow, one of these acetates resurfaced many decades later in Europe. One track — “Too Young” — appeared on a ’60s compilation disc and apparently became a cult favorite in Austria. Eventually Tom Lubin, who now lives in Australia, received the inevitable email from Raymond Dumont: “Dear Sir, are you the Tom Lubin who produced and engineered the band Prufrock in 1967?” And so, 40 years after those seminal Summer of Love sessions in Ojai, the Prufrock album — now called “Visions” — finally was released on vinyl in 2007. (It came out on CD a year later, and is available on Amazon.com.)

In 2009, Lubin had the further satisfaction of seeing the Rockets demos he had produced in Ojai in 1972 finally released as part of a Rockets CD called “Re-Entry.” (The lead singer is now billed as Eddie Money rather than Eddie Mahoney.)

Dean Thompson, of course, did not live to see these old Two:Dot recordings rediscovered and reissued. Lubin, who says he fell out of touch with Dean after moving to Australia in 1987, seems eager to share the credit with his old mentor. “I thank him for the opportunities and the support he gave me,” Lubin says. “He was a wonderful friend.”

Next it was finally the turn of “Hendrickson Road House,” the collectors’ favorite. Sue Randall was living in Oregon, still unaware of the intense interest in her old Two:Dot album. In June 2010, someone finally tracked her down and clued her in. A year later, “Hendrickson Road House” came out on CD, on the British label Wooden Hill. It contained some never-before-heard bonus tracks, most of them recorded on Hendrickson Road and preserved for decades in acetate form by the former Two:Dot technician Don de Brauwere, who remastered them and gave them to Randall for the reissue.

“I was very happy to be able to contact JoAnne Thompson to tell her that ‘Hendrickson Road House’ had come full circle,” Randall says. “I was happy to be able to say thanks to Dean for the incredible opportunity he gave me 40 years ago. I am indebted to everyone, even the jerks, who were instrumental in making this happen. I could never have guessed this outcome.”

FINAL VINYL

Hendrickson Road long ago was paved all the way to its end, so these days the uphill drive to the former Two:Dot site is a smooth one. The garage has gone back to being a garage, and is notable only for the presence of Darrell Jones’s lovingly restored 1947 Dodge sedan. Glenda has converted Dean Thompson’s former control room into an exercise room, and the only audio equipment it contains is her Bose CD-radio player.

JoAnne Thompson still lives in Santa Barbara, in a lovely home overlooking the ocean. Still very active at 83, she gives voice lessons, sometimes recording her students on a machine in her living room — a nice Two:Dot touch.

Ojai still boasts a lively music scene, along with a couple of spiffy recording studios. (The popular indie rock band Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeroes spent several months in the valley in 2011-2012 cutting their hit album “Here.”) Alan Thornhill plays at the Ranch House on Friday nights, and Milton Kelley has a regular gig at the Deer Lodge. Martin Young recently moved back to Ojai after many years as a big-time professional guitarist based in Nashville, and he often joins his old friends on stage. Few of their listeners realize it, but whenever Thornhill and Young play an old Country Z Men favorite, or whenever Kelley and Young play “Hard Way to Die” from “Home Brew,” they are offering a tribute of sorts to their Two:Dot days.

Young says he might look into the possibility of releasing those old Country Z Men demo tracks, “if we can find a decent copy.” Another intriguing possibility would be the demo he cut with Dan Protheroe, Jim Hendricks and Van Dyke Parks — if he can find any copy at all. “I’d give my left arm to have that recording now,” he says wistfully.

Is there anything else from the Two:Dot vault that is waiting to be rediscovered? Jeff Hanson doubts it. Not since Dean Thompson threw out all the unclaimed master tapes when he liquidated the studio’s inventory.

“There is no vault,” Hanson says. “There’s nothing left out there.”

But how can he be sure? Who knows when another Arthur Gee might come forward, a forgotten hippie troubadour clutching the only remaining copy of an old Two:Dot demo? Or perhaps that mysterious Englishman John Jones will one day re-emerge from oblivion clutching the tapes of his Two:Dot session, now hailed by collectors as a long-lost psych-folk masterpiece.

Dean Thompson’s studio was open to all comers, without filters, at a time when a great many people sincerely believed that rock music had the power to save the world. Some of those who recorded there hoped to sign with a major label and win fame and fortune. Others just wanted to testify; to add their voices to the heavenly choir. They sang their piece, paid for their records and went away. And life went on, and rock music did not, after all, usher in the millennium, and those records ended up stashed in a box in an attic and forgotten. Some are still there.

The Two:Dot catalog — whatever is left of it — beautifully documents this process as it unfolded here in Ojai, where the millennial impulse has always been strongly felt. No wonder collectors are drawn to these records. They offer the pure, unvarnished sound of the Sixties moment, lovingly preserved on vinyl, still waiting to be heard.

Originally published in the Summer 2012 edition of the Ojai Quarterly.

I did a lot of recording at two dot in the 70s.Great studio. Dean was great to work with & really knew his stuff. i still have the reel to reel tapes i recorded there. Nice to be able to share this.

Didnt Dean operate a big grading machine and grade out the orchad there on the corner across from the school? They planted Ojai Pixy tangerines? A guy last name Churchill do the development with Lyle Carson of the Carson Farm Supply?

And, didn’t Donnie Guido and Bob Nichols and Sal do an album there at Two Dot?