The following article first appeared in the April 12, 1972 edition of the “Ojai Valley News” on page D6. It is reprinted here with their permission.

Editorial by Fred Volz

Rare conversation with Krishnamurti about the Ojai Valley

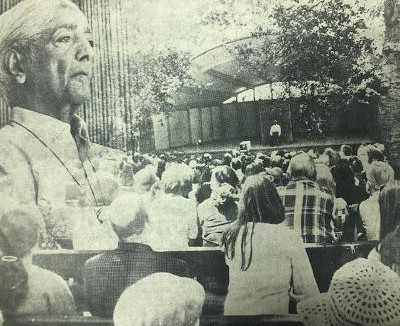

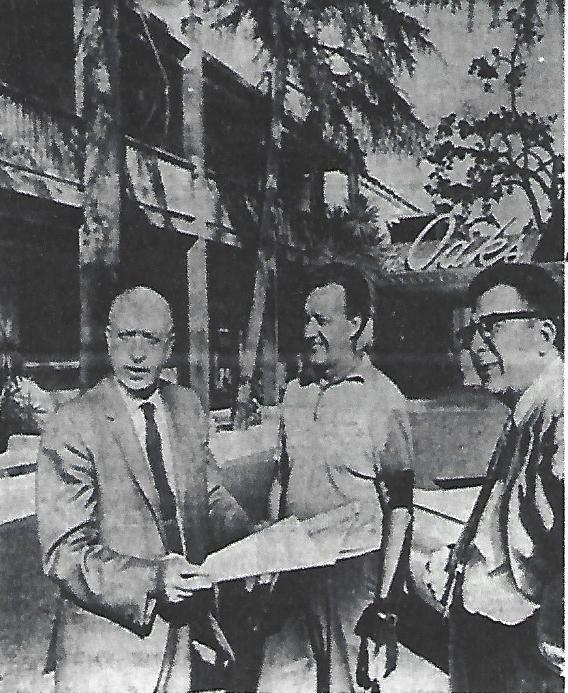

Last week our long-standing request to interview Jiddu Krishnamurti, world renowned philosopher, was granted. We spent almost two hours taping this interview, mostly about the Ojai Valley. Krishnamurti is now in New York City to give two talks at Carneigie Hall, before returning to England.

Krishnamurti is a slight, aethetic man with golden skin and large, soft brown eyes. He speaks with an Oxford accent in muted tones, pausing occasionally to collect his words.

He was born in 1895 in Madras, India, the eighth child of a Brahmin family. At 16, with his brother Nityananda, he was brought to England where he was privately educated. He first came here with his brother in the ‘20’s, and we begin our interview with that.

The conversation is almost an exact replica of our tape recording.

Sir, I feel that the people here would appreciate your views about the valley. May I ask you some questions about Ojai?

Krishnamurti—Yes.

Volz—You came here many years ago and you’ve stayed here from time to time. What are your personal feelings about the valley?

K—I came here first with my brother in 1922. We lived here. We came from India via Australia and lived in a little cottage. And the contrast was enormous. We came in July. The dryness, the heat, the dust. But we liked it enormously. It was the mountains. I’ve been practically all over those mountains, over all these trails. I’ve been up to Topa Topa, up to Chief. And I stayed here during the war . . . and off and on . . . treating this area as kind of my home. I also go to India, that is also my home. I stay in England—but this is one of the most beautiful valleys I’ve seen. I’ve been to Kashmir, and I’ve been to Switzerland, and parts of Europe . . . Pyrenees and various mountains in India. This has an extraordinary charm that the others do not have. It’s extraordinarily quiet at night. Wild. And I used to see deer up there . . . bear. Once, I walked behind a bobcat for several miles. The wind was blowing from him to me. So he didn’t smell me at all. Several miles . . . he was rubbing himself and enjoying himself. I don’t know whether they exist now.

V—Rare. Only very occasionally do I see one . . . just a flash.

K—And I see raccoons, foxes, and I’ve seen several times big brown bear. Marvelous. And somehow I like this place enormously. But I see it gradually being spoiled. I hear they want to put a highway through here. That’s the end of this valley. And they want to develop parts of it . . . a tourist resort and all that. I suppose this is what is really happening all over the world. When there’s a beautiful spot, they want to destroy it . . . exploit it touristically for economic purposes. I know a place in India, a beautiful place, but it’s spoiled now by overpopulation. Get rich quick. Recently, I stayed as a guest in Malibu and they’re destroying that whole hill. Terrible.

V—Well, you’ve answered the first three questions I have. I was going to say you saw Ojai then . . . and you see what’s happening now. I was also going to ask you what exceptional qualities Ojai had in the twenties and what it does not have now.

K—This East end has still got it. Because I can go up one of those hills and not see anyone. In those days I would go . . . oh . . . miles and miles . . . but now it’s gradually being pushed out. It will be destroyed. Unless you all stand firm.

V—Do you see any change in the way it’s going now. Or is gradually the land being used up?

K—I’m afraid so.

V—You don’t see a change. Is there anything we could do about this?

K—Ah, I suppose . . . I don’t know why the government . . . or people congregate . . . and say this is one place in California that should be kept the way it was. Or it will be completely wiped out.

V—As a result of economic motives?

K—The way we are going now in America . . . and the rest of the world . . . in 70 years through overpopulation man will destroy himself.

V—There have been encouraging things happening here recently. For example, the Meditation Group—the private schools . . . Happy Valley, Ojai Valley, and Villanova. So there has been a move in that direction. People coming here to build schools and have them expand. Do you see anything happening here along those lines?

K—Let me tell you about Happy Valley. We came here in 1922. In 1927, Dr. Besant . . . the Happy Valley Foundation . . . she started it . . . she bought land, mortgages and all that. She bought it for one purpose . . . I don’t want to be personal . . . that the teachings that K was giving would bring around a different group of people. Happy Valley land was to be used for that. And now it’s gone into other people’s hands . . . unfortunately. But schools here, if there are a great many schools here. What would happen? Can they maintain themselves? Private schools.

V—They come here for the very reason you and I come here. A beautiful, quiet, peaceful place . . . conducive to study.

K—I believe private schools are suffering a great deal. You see I used to talk practically every year at the other end (near Krotona Hill at the Oak Grove). Many people came here . . . gathered and had camps and all that. It’s all different since then. I’ve not been here practically since 1965. But I could come every year. Things have changed. Can’t serious people come here and maintain this atmosphere and this kind of beauty?

V—I think a lot of us are asking that question. I’m not so sure it’s good for the economy of the valley to have more houses, more people. The very reasons we all came here will have been destroyed.

K—How can we prevent the others from destroying it?

V—I think we’ll just have to say no. That the government will have to say no. That the valley should stay in orchards. In open space. I thought of one time writing to our congressman and proposing this as a national park . . . like Yosemite, like Yellowstone.

K—Will they allow it?

V—Well, the list of proposed national parks is long now. A very beautiful place north of San Francisco in Marin County is the newest national park . . . a strip of original seashore . . . in native grasses and sand. It has been preserved in the hands of one family ever since the Spaniards were there. This is the newest national park. Pt. Reyes National Park. We had our hand in proposing that. Now . . . in the Napa Valley . . . with its vineyards . . . they have made that into what we call a national monument which prevents any change to that valley. Not a park, but a national monument. Yet, it’s not as beautiful as this.

K—We have a school in England in Hampshire. There’s the start of a building there . . . the K Foundation owns it. You can’t build new houses . . . you can only improve or pull down old houses. You have to build on the same foundation. And you have to get permission to build from the planning committee—anything at all. We were going to build for 40 people. It took six months to get permission. It’s only an hour from London by train, but it’s a beautiful place and they said let’s not go and destroy it.

V—I think that’s what happened initially to our great national parks. Yosemite . . . John Muir in particular . . . said we’re not going to destroy this. This has to be kept. They brought United States officials there. And they agreed.

K—Can’t this be done here?

V—One of the problems — I was just thinking about this — it’s an exceptional day outside. If you live here long enough, you begin to think the whole world is like this. And it’s not. Locals don’t understand . . .

K—Can’t Ojai be maintained, sir. Through influence . . . through the machinery of government?

V—Let me say, I’m much more optimistic now, than I was last year for the Ojai Valley. Finally, the people who are in charge are getting the message from all of us down below, that we don’t want this to change, we don’t want more shopping centers and tract houses. We want to keep what’s left. What do you think that the citizens here can do?

K—Sir, do you know what is happening in the world? The citizens are responsible for destroying the world. Hmm? I used to go to India, except this winter. Every winter I spent 5-6 months . . . now it’s reduced to 3 months. You have no idea how it’s being destroyed. In Bombay, people are sleeping on pavements. Thousands of them. And under the tree they sleep. And the villages are being destroyed . . . 10 million of them. And the death rate is not so great as the birth rate. Citizens . . . human beings are responsible for this. Why can’t they stop it? Here in this valley . . . live all of you . . . for God’s sake you preserve this place. One place that’s not destroyed. Do you think there are serious people here? Serious in the sense . . . not all economically well established . . . but have roots in the valley . . . serious-minded people who say let’s maintain this atmosphere…this quietness, this beauty, this sense of . . . otherness. Do you know what I mean? Not at all the wrangles of the Catholic, Protestant, Communist, Socialist. Do you think there are such people here?

V—Yes, I think so. Many people of every political and religious affiliation feel exactly the way we do. Recently, a Committee to Preserve the Ojai was formed. They have four-five hundred members and they’re seeking to influence the kind of people who get elected. Working to defeat unneeded shopping centers. They’re working in a very practical way. And their numbers are growing. More people feel sympathy for them . . . and give them money. So, it’s happening here . . . but it has to happen fast. It can’t wait. There has to be a change in thinking. We all have to realize that open space out there is valuable. The most valuable thing we have. Of course, I write about this all the time to the people of Ojai. I don’t know how much attention they pay to it. Nothing much seems to happen. But I like you saying that.

K—You know, sir, in India, in Greece, and in other civilizations, when they found a beautiful spot like this they put a temple. Not a Christian temple or a Buddhist temple, but a temple. A thing that was beautiful and remained sacred because of the beauty of the place. I go to a school in south India. I spend three weeks talking to children. As you enter there, on a hill is a temple. And the feeling you have is of a sacred place . . . be quiet, be nice, be gentle, be pleasant to your neighbor, don’t kill, don’t hurt . . . all that atmosphere makes for beauty.

V—Do you think Americans are different from other people?

K—They’re much more energetic. They’re pleasure seekers. They’re fleetingly serious. I never have seen such race as this that want to . . . they can’t sit quietly. Go to the lakes, go off on guided hikes . . . oh . . . they can’t be by themselves. One year I was walking right up there on your mountains. I was standing looking at the beauty of the land . . . I could even see the ocean . . . A man came down on horseback . . . I was standing very still . . . He said, ‘what the hell are you standing so still for?’ . . . I said, ‘isn’t it a beautiful day?’ He looked at me and said, ‘oh, you’re the Christ child.’ (Much laughter here).

V— That was many years ago, wasn’t it?

K—Yes. I wonder, sir, you know Ojai. Can people treat this valley as a sacred place . . . not as a commercial center? A sacred place becomes beautiful . . . I hope you understand. People will come here because it’s quiet, restful, thoughtful, serious.

V—You don’t see any formal change . . . like, people coming here to form a religious center or a spiritual center. In the practical sense of the word.

K—I would . . . you see, sir, in India we have a place like this. A school . . . but people who come there are serious people. Treat it . . . I hate to use the word . . . as a sacred place. Unless you have this spot where people really can be thoughtful and serious you are going to destroy the world. You’ve heard of the river Ganges in India. We have a school on the banks of it, and it is very old. I found a statue by digging in the garden which is 6th century. Before that, I found something from B.C. So there’s a tremendous sense of atmosphere. I was talking the other day to Frank Waters and he was saying the American Indians felt the land was sacred and the sky was sacred. So keep it clean, keep it unpolluted. Here there isn’t that attitude . . . that feeling for the earth.

V—Yes, we’re supposed to conquer nature.

K—That’s it . . .

V—It says so in the Bible.

K—I know. In the East, there is a respect for the earth, respect for animals . . . not kill them. Here, you must always use it, build a factory, tear it to pieces. There’s that enormous vitality. Every time I used to come back to Ojai, before 1950, I say, “what a marvelous place!” But now I don’t come because it’s marvelous.

V—It would seem to me it would help much . . . if you would come here more often.

K—Oh yes. I’m coming . . . I didn’t come because the people I was working with didn’t want me to come here.

V—When you come, will you be staying here for a long time?

K—Oh, yes . . .

V—Well, this place will become what we think it should become. If we think positively about it, if we think this is the way the Ojai Valley should be, it will be that way.

K—That’s right. You know, Ojai Valley, is known all over the world. Because of the K Foundation. There’s a K foundation in England, in South America, and in India. People want to come here. That’s why that Happy Valley was bought. By Theosophist, by a group of people of whom I was the head. It was for that. Now it is . . .

V—It’s still there, the land, isn’t it?

K—But they’re different . . . and not interested.

V—I’m pleased to hear that you will be back.

K—Next year.

V—Do you plan to give up your place in Switzerland?

K—No, sir. There will be a gathering there. For about 3 weeks from all over Europe. And we’ll go on with that. And we’ll go on with Ojai, on with India. I used to go to Paris, Amsterdam, to various towns, but I’ll be glad to give this up.

V—Sounds like you’re more active than ever.

K—Let me tell you a true story, sir. In India, one time I was doing Yoga exercise and I see a shadow in the window. There is a big black wild monkey. I come quite close and it stretches out its hand. And I hold its hand. And its hand was rough and he wants to come inside. I said, ‘I don’t have time today . . . but come and see me sometime.’

V—Well, I understand you rarely grant interviews . . . on behalf of myself and the people of the Ojai Valley, I thank you for your time.

K: You are welcome, sir.