The following article first appeared in the January 3, 1973 edition of the Ojai Valley News. It is reprinted here with their permission. The article was written by Howard Bald. Bald used the same title for all of his articles. So, the Ojai Valley Museum has added “No. 10” to the title. All photos have been added by the Ojai Valley Museum.

Reminiscences of Early Ojai (No. 10)

by

Howard Bald

It was always quite an occasion for mother, sister and me to drive to Ventura with the horse and buggy. The present highway did not exist then. The 15 mile drive down the Creek road with the numerous creek crossings took from one and a half to two hours, and the return trip from two to two and a half hours.

On the beach west of the Ventura pier we unhitched Charley and tied him to the rear of the buggy with a nose bag of rolled barley while we spread a blanket on the sand and ate our lunch.

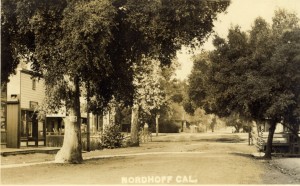

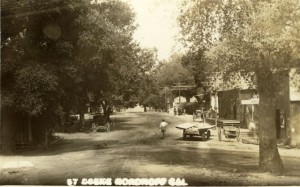

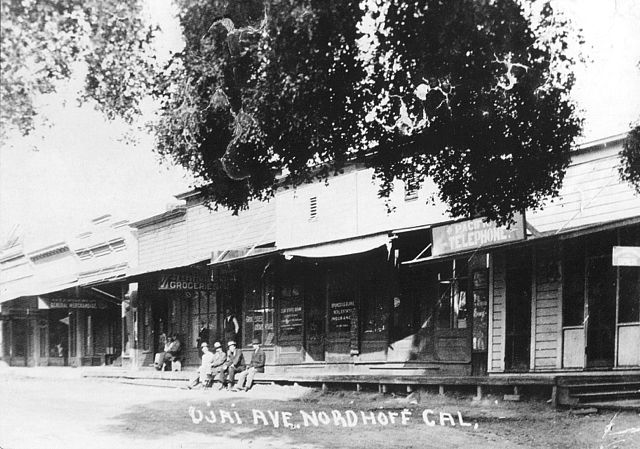

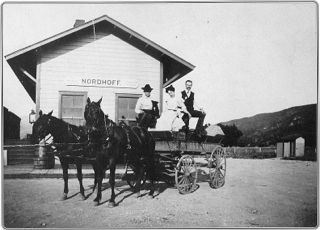

The present direct route to Ventura didn’t go through until about 1917, so all travel was via the Creek road. From Nordhoff to Camp Comfort the road was much the same as it is today. But just below Camp Comfort it crossed the creek, then a mile or more beyond it recrossed the creek, finally emerging into the present highway at Arnaz, between the famous old Arnaz adobe and the present cider stand.

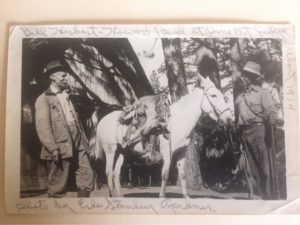

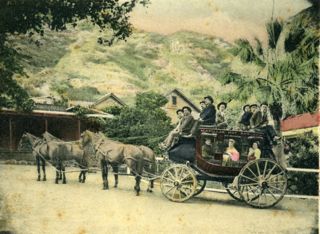

The mail was carried by four horse stage, as was also express and other special items. Of course there was no refrigeration in those days, and ice was brought up by stage. It was said that on a hot day the stage could be trailed all the way from Ventura by the mark left on the dusty road by the melting ice. I think it was about 1907 that Mr. Houk (Fred Houk’s father) put in an ice plant.

There would be times in the winter when the stage would be held up for days because of high water. I think it was the winter of 1905-06 that the mail was held up for three weeks. It was that winter that Herb Lamb was the stage driver (Margaret Reimer’s father had the mail franchise then), and on one trip Lamb had his wife and infant among the passengers when the stage turned over in a creek crossing. The infant was swept away and never found.

There were other drownings in the streams in those days. One time (I believe it was 1914) a group of men over in Santa Ana (among them John Selby and Gird Percy) rode on horseback to the Matilija river canyon below Arnaz. One of the group ventured in, was swept away and never found.

I don’t remember what year it was that Bob Clark was living on the far side of the river and was stormed in when a baby was due. He had one saddle horse, “Dick,” that he would take a chance on. Dick got him across the river at what is now Casitas Springs. (We called it Stoney Flat in those days.) He took a team of horses and wagons from there, drove to Ventura and returned with Dr. Homer, as there was no telephone communication in those days. Old Dick carried the two back across the river. I believe Dr. Homer stayed three days before the baby was delivered. Dr. Homer is now retired to the Ojai.

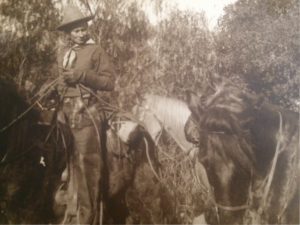

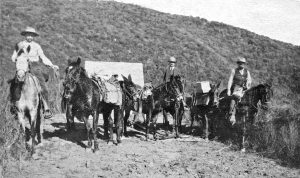

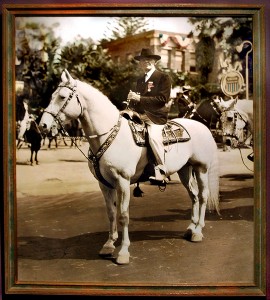

Tom Clark had quite a reputation in those days for crossing roaring streams when no one else would venture in. There was one famous occasion about 1888 when he took a young lady and her trousseau over Sulphur Mountain with saddle and pack horses to Ventura, where she took a steamer to San Francisco. The young lady was Bessie Thacher, the aunt of Anson and Elizabeth Thacher.

The valley had its highway tragedies in those days too, only they didn’t involve automobiles, but horses. Captain Gillette (who lived where Dr. Rupp’s office now is) was killed someplace near the present Country Club. Judge Hines went over a precipice near Topa Topa ranch with a team and buggy. Mrs. William McGuire, of the Upper Ojai, was thrown from a horse and killed on Ojai avenue. Chino Lopez, to keep warm, placed a coal lantern under the buggy robe (he was blind), the buggy went off the grade in Matilija Canyon and he burned to death.

A Thacher student boy in 1904 was thrown from his horse and dragged to death. A Gibson boy, whose family were Upper Ojai ranchers, was crushed by a falling horse. Then some time later the father, Mr. Gibson, was thrown from his buggy in a runaway and killed.