The following article first appeared on the front page of the Friday, May 24, 1935 edition of “The Ojai.” “The Ojai” is now the “Ojai Valley News.” It is reprinted here with their permission. The author is unknown.

Early School Days in Valley Recalled for Clara Smith’s Party

A committee of the grammar school Junior Red Cross attempted to compile a history of the schools of the Nordhoff district, for inclusion in the memory book to be presented to Miss Clara Smith a the banquet celebrating her 50 years of teaching Tuesday evening. But Mrs. Inez T. Sheldon, principal of the school, reports the task a difficult one because memories conflicted. However the following was put together as the best record that could be secured:

First School in Valley

In the extreme east at the foot of the grade on the left going toward Santa Paula H. J. Dennison taught perhaps a dozen children even earlier than 1869. A path up the grade led to the spring just beyond the present first sightseeing stop (Lookout Point) almost to the top of the grade. The big boys carried water if the barrel became empty before the appointed time to haul the next barrel full.

The district then comprised all of the present Matilija, Upper Ojai, and Lower Ojai valleys. The school was laughingly called “The Sagebrush Academy.” The last teacher there whose name no one seems willing to recall was at any rate a very loyal Democrat. He presided strictly—chastising the children of Democrats lightly with a pure white ruler, while little Republicans suffered under the strokes of a very black longer ruler.

In 1895 Mr. Van Curen circulated the petition to divide the district. Inez Blumberg (Mrs. J. B. Berry) and Miss Nina Soule remember Miss Skinner vividly. Earl Soule was too young but learned “his letters” in the second school, the one-room brick.

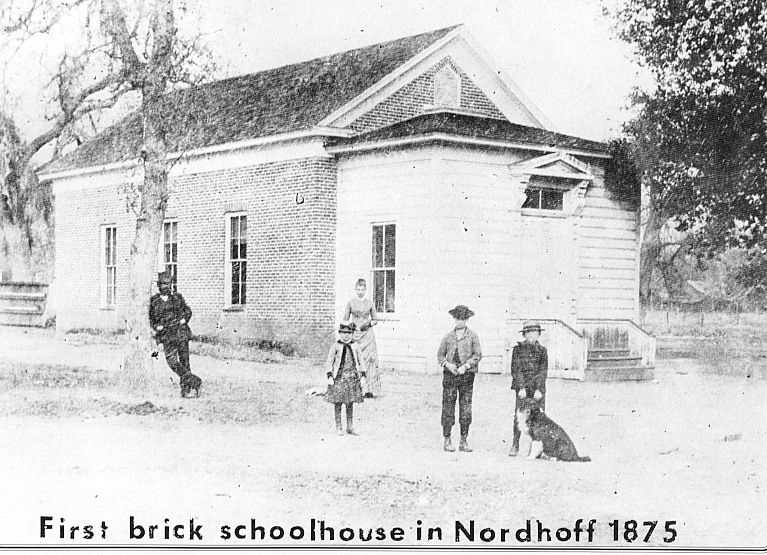

Brick School

On the present Alton L. Drown residence property, 244 Matilija Street, then an unoccupied tract, was erected the first Ojai School. The sagebrush academy was removed to the Dennison ranch, and later again to the present Upper Ojai where Mrs. E. P. Tobin is now teaching.

While the bricks were being made near the present tennis courts of the Civic Center, a small temporary shed was hastily put up on the same lot to house the school. Rough boards stood straight up and down. Horizontal boards for the roof kept out the sun. On planks facing the wall the children sat using planks against the wall for desks. But this was necessary only a short time. And the little brick school seemed verily a palace, laughingly recall the Soules, Piries, Bakers, John Larmar, and others. A. W. Blumberg made the bricks, and his daughter has an interesting souvenir—a brick on which a lion left his track. The hole from which the clay was taken may be seen to this day in the Civic Center near the railroad.

Noted Pupil

In the biography of David P. Barrows, former president of the University of California in Berkley, it is written that he learned his “ABC’s” with his little bare toes dangling over Mother Earth from rough wooden boxes in which nails had been surreptitiously placed as seats. At least this is found to be historic!

Steepleton Private School

On the present Y-T ranch, just off Grand Avenue, a mile and a half east of the village, in 1874, Mrs. Joseph Steepleton, who later taught in the new brick school, kept private school. Also in the same location as late as 1928, Frank Gerard established a private school. Both private schools were short lived. Mr. Barrows recalls many funny experiments in the old brick school. It is suggested that he be asked for his “wart yarn” when next he visits Ojai.

The Fruit Pickers

Mr. Buckman, the first county school superintendent of Ventura, was one of the first teachers in the brick building. He planted the first orange tree in this now famous valley. Also he grew strawberries to help maintain his financial independence. By getting permission from home, his pupils were permitted to go from school during school hours, to the Topa Topa ranch, (then his home), and pick his strawberries for him. Great was the jealousy of those whose parents would not permit them to stop studying their three R’s long enough to go up to the ranch to pick berries.

So few of the school registers are to be found of the old brick days that only an attempted list of the teachers there can be recorded. Miss Allen, Miss Haight, Mr. Goodman, Mr. Alvord, and Miss Hawks taught before Miss Agnes Howe, who was probably there the longest time of all. She was Miss Clara Smith’s first teacher in California.

Miss Smith had taught in Ohio but here more education for a teacher’s certificate was required so for a short period in 1884 she was a pupil in the old brick school. Thompsons, Clarks, Robinsons, Hunds, Ayers, Spencers, and others already mentioned remember those “old days.” After studying in Santa Barbara, Miss Smith returned and taught in the same brick building. Eva Bullard Myers, Bill Raddick, the Gally brothers, Sam Hudiburg, and others, were some of her pupils.

After teaching in the Ventura schools at the same time that Miss Blanche Tarr taught there, Miss Smith worked her way through the State University at Berkeley and returned to Ojai to teach three years in the new building at the corner of Montgomery and Ojai Avenue. Fred Linder, S. Beaman, and Clark Miller were pupils of hers at this period.

Brown Bungalow

When perhaps as many as 60 pupils were enrolled, it became necessary to add a little brown school, one room, on the same lot as “the new brick.” Miss Pellam taught the little people there until it was moved. George Black, Ventura County School Superintendent, and later the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, married her sister. In 1895 both schools on this site were purchased, the brick building vacated, and the little brown school moved to its present location, 570 North Montgomery, on the Snow property between Millard’s and Lafkas’.

It is interesting to note that the present Drown residence was built by J. E. Freeman in 1911, on the same brick foundation as the old school building. Captain Sheridan of the old Ojai Inn, grandfather of the Sheridan brothers, was responsible for the laying of these bricks.

The Wolf Family

The Wolf family had the first good pictures of this section. Mr. Wolf acted as a trustee of the district, and interested himself considerably in the work. Quite tragically one day his son fell from an oak on the school and was killed.

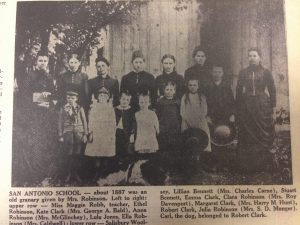

San Antonio School

Mrs. Lillian Bennett Carnes, Mrs. Margaret Hunt, the Mungers, and Ryersons, tell many fascinating stories of the first San Antonio school, located on Ojai Avenue on what is now the Edward L. Wiest property.

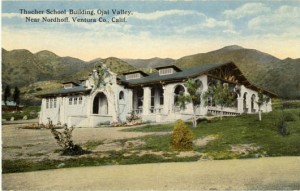

Thacher School

Sherman D. Thacher was refused a position there, being told to go on with his little orange grove. Thus in 1889 with only one pupil this now famous Thacher School was begun.

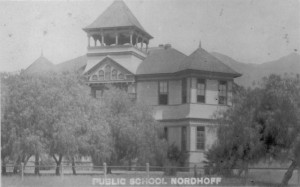

The Present Wood Building

The wooden grammar school building was first occupied in 1895. It was moved back on the northeast corner in 1927. The sum of $1,250 was paid for the lot. The bond issued failed by one vote at the first election, but was carried for $9,000 at the second one. Mr. Zimmerman was awarded the contract for $7,825. However the building of the assembly hall with the other incidental expenses brought the total cost to around $10,000. It was necessary to use the money obtained from the sale of the “brick school” and the “brown bungalow” plus the building fund, plus the school bonds, to meet this debt.

Miss Mabel Pendergriss was presumably the first teacher in the new school. Amy Hamlin, Eleanor Hammack, Anna Cordes, and others are recalled, but C. L. Edgerton is always remembered when anyone is asked regarding the history of the building. For ten years following the time Miss Smith taught there, Mr. Edgerton was principal.

First High School

The year 1909-10 was W. W. Bristol’s first year as the first principal of the first high school in Nordhoff. School was held with Miss Maybyn (Mrs. Howard Hall) assisting, in the upstairs of the grammar school building. Miss Ruth Forsyth assisted Mr. Bristol the second year. School was so crowded it was necessary to send some freshman to the lower floor under Mr. Edgerton’s supervision.

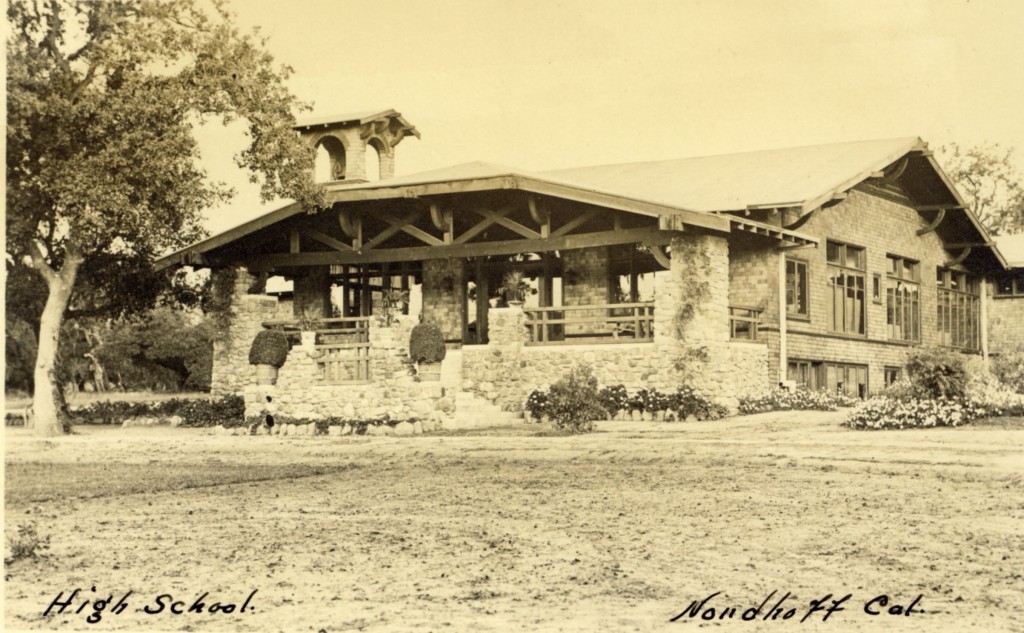

High School Building

May 17, 1909, there were 108 votes cast for establishing a high school, and six votes against. Of the 25 pupils that first year Edna Leslie (Mrs. Edna Grout) rated as “the best citizen”, and Grace Hobson (Mrs. Fed Smith) as “the best scholar.” The bond issue voted the following year was 151 to 8 for $20,000. Words fail to express the hot times over the proper location of what is now known as the Junior high school. The first trustees are all deceased: S. D. Thacher, F. H. Sheldon, Frank Barrows, Mr. Hobart, and Dr. Saeger. Irma Busch (Mrs. William T. Frederick), Abbie Cota Moreman, Carolyn and Thornton Wilson were in this pupil group.

Old Grammar School Building

When J. F. Linder was first trustee of the grammar school (1912-13) there were 82 children enrolled, and four teachers using all the rooms. Queen E. Kidd was principal, with Katherine Donahue, Olivia Doherty and Celia Parsons as teachers. The principal received $810, the teachers between $675 and $712.50. W. A. Goodman, Mrs. Canfield and E. L. Kreisher, up to 1919 earned $1,200. Miss Abbie Cota and Miss Edna Leslie were teaching during this period; also Mrs. Fred Burnell as Mrs. H. S. Van Tassel and as Mrs. Louise Thompson.

Miss Iris Evans graduated in the first eighth grade held in the old grammar school. In 1924 the 7th and 8th grade books were transferred to the Junior high. Her brother Jim in June, 1925, was in the first sixth grade graduating from the grammar into the Junior high school. Roscoe Ashcraft was principal both years. Miss Anna Gilbert (Mrs. Sexton) preceded him. Mrs. Hathaway and Miss Agnes Howe returned and both were principals during the time the old wooden building was in use.

Matilija

By private subscrition in 1890, W. L. Rice, carpenter and liberal contributor, built the first little Matilija school near the river bed in a lovely oak tree setting. Anna Stewart was the first teacher. The three Soper children, three Rice girls, Blumbergs, and Lopez children were the first pupils.

There were 20 different teachers in the 24 years before February 20, 1914 when in the flood the building was completely washed down stream. A small building was immediately erected on this side of the river, high and dry. It was located on the Meiners’ property a half mile from the Rice residence at the corner. Miss Mary Freeman taught here, and Mr. Krull of the present Johnson place was the Matilija trustee until his death. Four years later the building was sold to the Matilija rancho and removed while the lot reverted to the Meiners’ estate. Miss Pope leaves a very complete record of this period.

In 1918 Matilija united with Nordhoff Union grammar school district. This district averages 10 to 15 children to educate and great was their rejoicing when the school bus in 1919 regularly transferred the children to Ojai.

Nordhoff Kindergarten

In 1920, ten pupils attended the first kindergarten established in the Valley with Miss Clara Newman as the teacher. The next year, in 1921, the name was changed to Ojai Kindergarten.

Miss Matilda Knowlton (Mrs. Joe Misbeek) taught in the Boyd room at the Woman’s Club for four years with an average daily attendance of 25. Then, in 1927, Miss Ruth M. Hart (Mrs. John Recker) moved across the street into the corner room of the present stucco building.

Following is a record of the teachers and the number of kindergarten pupils since that time:

Mary A. Wharton (1928-29) 26; Alice Connely (1929-30) 26; Mrs. Gladys Raymond (1930-31) 31; Elizabeth Pell (1931-32) 23; Elizabeth Pell Wellman (1932-33) 23; Mrs. Mildred Rodgers, present teacher.

Arnaz School District

Dr. Jose Arnaz of the large Arnaz land grant in 1877 gave to the County Superintendent Buckman (formerly of the Nordhoff brick school) the use of one room in his home for a school. His second wife was Adolph Camarillo’s sister, Pet Seymour, who later became Mrs. Drake, was the teacher. Mrs. Ventura Arnaz Wagner recalls how comfortably several years were spent until John Poplin arrived and agitated for a new school building. He hauled and donated lumber as well as contributed labor to the new plant. It was, and still is (what is left of it) a mile from the cider mill (Fergerson or Arnaz home) on the Creek road a few steps down off the present highway (Fergerson grade.) During heavy rains the footbridge washes out and of course it was impossible to hold school.

Young Dick Haydock was the first teacher in this new schoolhouse. He boarded with Poplin who became clerk of the board, until Mr. Healy moved in. Very soon he “ran the school” and the teachers boarded there. His children were the only American children in school at that period.

T. O. Toland’s wife taught this school in 1888 so it probably had been opened three years. Little of note occurred after Mr. Welsh’s resignation until the fall of 1926.

By the fall of 1926 the school had grown to such extent that it became necessary to expand into the coat room. Mrs. Hubbard was the teacher in the school room while Gretchen Close taught in the coat room. However very shortly, Miss Close’s room was moved to Laidler’s grocery store in Casitas Springs. This was the living room in which were housed for a time 37 school children.

Arnaz united with Nordhoff Union grammar school district in 1927. Mr. Nye was their representative on the union board of five members. This section is in the unique position of being part of the Nordhoff Union grammar school district and the Ventura high school district. At the present time, May 1935, Arnaz uses two school buildings, the Casitas Springs buildings, and the Oak View Gardens building.

Casitas Springs School

Mr. Nye in 1927 gave the present school lots to the district with the request that the building be known as the Casitas Springs school. A one-room school was built by Mr. Hitchcock at the contract price of $2,407. Miss Hattie Conner was the first teacher with 43 children in the three grades. All the children of grades four to six were transported by bus to the Nordhoff building.

Mr. Nye was succeeded as school trustee in 1928 by Charles G. Crose, who was succeeded by Victor McMains, and now I. V. Young is trustee for the district.

The teachers in the Casitas Springs school were Hattie Conner, Mrs. Paul Woodside, and the incumbent, Miss Ruth McMillian who has held the position since January, 1930.

Nordhoff Stucco Building

The stucco building of Nordhoff grammar school was built by Johnson and Hanson of Santa Barbara. They were awarded the contract for $34,982. J. R. Brakey had the $1,600 contract for moving the old building back on the northeast corner. Heat, lights, plumbing, blackboards and furniture increased the cost to around $48,000. During Mrs. Inez T. Sheldon’s first year as principal it was found necessary to add a teacher (Mrs. Estes, the wife of the principal of the high school). The assembly hall held two classes and the next year Mrs. Murphy taught in the Boyd Club where the Little Theatre now is. Then in 1927 after the uniting of the Arnaz with Nordhoff, eight rooms of the present building were filled to overflowing. It was two years before the last three rooms were added.

The old building is entirely occupied now and there is a faculty of 18. From 150 pupils in Mr. Ashcraft’s last year, the school has grown to 589 in 1934-35.