Turn of the Century Ojai by Howard Bald

Note: Howard Bald was an early Ojai resident. These reminiscences were probably written in the 1960s.

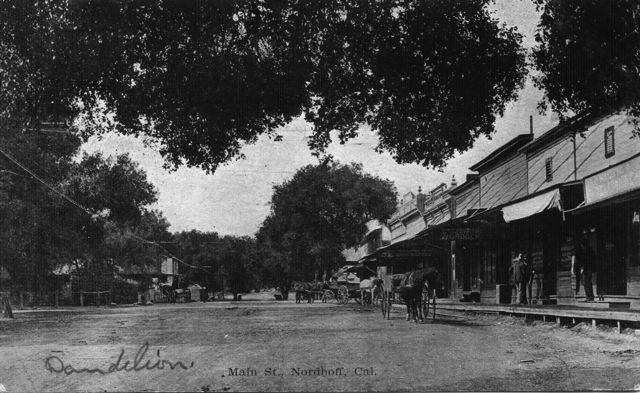

Nordhoff (now Ojai) has generally been described as a quiet, peaceful little place, and generally it was. Several oak trees strung along Main street from Tom Clark’s livery stable to Schroff’s harness shop furnished the only shade, for there was no Arcade until 1918-19 [1917].

Nordhoff (now Ojai) has generally been described as a quiet, peaceful little place, and generally it was. Several oak trees strung along Main street from Tom Clark’s livery stable to Schroff’s harness shop furnished the only shade, for there was no Arcade until 1918-19 [1917].

There were three gaps in the row of buildings on the north side of Main Street. One was between Lagomarsino’s saloon and Archie McDonald’s blacksmith shop at the east end of the business block, about the location of the Edison office and Barrow’s hardware store [Rains Department Store] stood alone. There was an alley on both the east and west side of that building, which I think was the site of the present hardware store.

The east alley was used by pedestrians. I think the board sidewalk prevented vehicles going through. But the sidewalk ended at the west corner of Barrow’s hardware, so that alley was quite generally used by horsemen as well as pedestrians.

West of that alley was Bray’s plumbing shop, and from there on to Signal street was the livery stable with its buggy sheds, corrals and hay sheds. West of Signal on the site of the Oaks Hotel [The Oaks at Ojai] stood a small, whitewashed, clapboard house where chet Cagnacci was born at the turn of the century and later, I believe, Tommie Clark.

Across the street about the site of Van Dyke’s Travel Agency [Friends of Library book store] stood Dave Raddick’s residence, then easterly a break, then the meat market.  On the southwest corner of Signal and Main was The Ojai newspaper printing office where the theatre now stands and easterly across the street, where the present post office is located, was Charley Gibson’s blacksmith shop. There was quite a gap between the blacksmith shop and Lauch Orton’s plumbing shop, the barber shop and post office. Through that gap could be seen the Berry Villa, which is now the post office employee’s parking place.

On the southwest corner of Signal and Main was The Ojai newspaper printing office where the theatre now stands and easterly across the street, where the present post office is located, was Charley Gibson’s blacksmith shop. There was quite a gap between the blacksmith shop and Lauch Orton’s plumbing shop, the barber shop and post office. Through that gap could be seen the Berry Villa, which is now the post office employee’s parking place.

A little distance east of the post office, briefly, stood C.B. Stevens little grocery store, then the entrance and exit to the Ojai Inn which is now our city park. A leaky, redwood horse trough and a hitch rail extended onto the barranca. It was always shady, and teams of horses and buggies were customarily tied there while the out of town folk did their shopping.

I once had a Plymouth Rock hen who would bring her brood through the alley between the saloon and blacksmith shop to scratch around where the horses were tied. Sometimes she would miscalculate and be overtaken by darkness, so hen and chicks would simply fly up on a vacant spot on the hitch rail and settle down for the night. Our stable and chicken coop was just back of Dr. Hirsch’s office [next to Lavender Inn] and more than once at about bedtime, I would carry them back to their own roost.

Schroff’s harness shop east of the barranca stood high enough from the ground that one could step from a saddle horse onto the porch, which was convenient for ladies riding sidesaddle to dismount and mount.

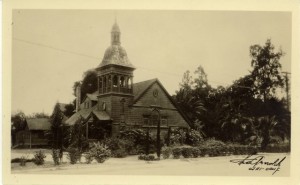

The corner of South Montgomery and Main [now Ojai Chevron Station] was open and was used mainly by Thacher boys to tie their horses while attending services at the Presbyterian church, which stood where the Chevrolet parking lot now is [parking for Jersey Mike’s]. That building now is the Nazarene Church [Byron Katie Center] on N. Montgomery and Aliso.

was used mainly by Thacher boys to tie their horses while attending services at the Presbyterian church, which stood where the Chevrolet parking lot now is [parking for Jersey Mike’s]. That building now is the Nazarene Church [Byron Katie Center] on N. Montgomery and Aliso.

I could go on and on and on with details of the village of Nordhoff at the turn of the century, but I fear that would become too boring, so I will get on with some of my memories of the activities of the time. (To be continued in future installments.)