Matilija and Casitas Dams by Patty Fry

The Valley’s rising population in the 1930s and 40s increased the demand for water. That demand was also evident in Ventura and in 1944, an act of the legislature formed the Ventura County Flood Control District. They employed Donald R. Warren as consulting engineer to evaluate the local water situation and he recommended a $3 million bond issue to construct a dam in the Matilija Canyon and another on Coyote Creek.

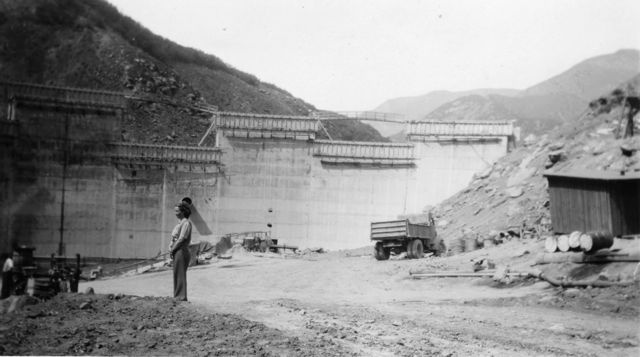

[Construction began in June, 1946.] The Matilija Dam project met with major problems. Unexpected delays, rising costs and heavy criticism plagued the job. Clay began oozing from under the dam foundation in Matilija Canyon, and the carpenters walked out. The dam was eventually deemed unsafe and a lawsuit against the engineering firm ensued. This proved to be a very costly decision.

Finally, despite all of these adversities, the site was judged safe and the workers completed the Matilija Dam in June, 1948. But the beautiful new dam stood embarrassingly empty for three years, as a severe drought was in progress. There wasn’t enough rain during that time to make more than a mud hole of the huge reservoir and that is what water customers were getting–mud. Finally, during the winter of 1951, a storm produced enough rain to fill the reservoir to capacity and the first spill occurred the following January [1952]. Conduit pipe carried water to the spreading grounds near the mouth of Senior Canyon at a rate of 1,350 gallons per minute. This water percolated into the ground and helped replenish the wells below.

By March, 1952, 44,960 acre-feet of water had been lost over the Matilija dam spillway to the ocean. It was evident that a larger facility was necessary, especially when considering the long-range water picture. In the meantime, geologists tested a dam site at Coyote Creek. A possible fault caused the project to be canceled, but after further investigation, this decision was reversed. Consultants for the flood control district recommended a 90,000 acre-foot reservoir on Coyote Creek to stop the Matilija overflow, and the project was approved.

The Federal Bureau of Reclamation completed Casitas Dam in 1959. …Casitas Municipal Water District presently operates Matilija Dam, which is owned by the Ventura County Flood Control District. No water is served to customers from this source. Lake Matilija is used primarily to store water during flood periods for later transfer to Lake Casitas.

The above is excerpted from Patty Fry’s book The Ojai Valley: An Illustrated History. The book was updated in 2017 by Elise DePuydt and Craig Walker. It is available in the museum’s store and through Amazon.com.

The above is excerpted from Patty Fry’s book The Ojai Valley: An Illustrated History. The book was updated in 2017 by Elise DePuydt and Craig Walker. It is available in the museum’s store and through Amazon.com.