The World and Ojai Change Forever, from The Ojai Valley News, 1991

Betty Jo Bucker Strong of Ojai was attending services at the Ojai Presbyterian Church on December 7, 1941, when news broke that Pearl Harbor had been bombed:

“That Sunday’s afternoon excursion for us teenagers was immediately canceled, and we all just stood in front of the church absolutely numb,” she recalls. “Within days, we were ordered to tar-paper our windows at night, and we held regular air raid drills. My mother learned to shoot a rifle.”

Ojai on the Defensive

With the declaration of war, Ojai Mayor Fred Houk issued a proclamation creating a Civilian Defense Council to coordinate “all war and defense measures in the city and the community.” Routine blackouts and air raid drills were signaled by the bell in the post office tower, and civilian wardens with whistles patrolled the outlying neighborhoods to warn householders to douse their lights. Stores in the Arcade conducted end-of-the-day business behind draped windows, and cars were ordered to pull over and turn off their headlights.

Less than three months after the start of the war, on February 24, 1942, the Ojai Valley’s readiness was put to the test when a Japanese submarine slipped into the Santa Barbara Channel and fired 20 rounds from its 5-inch guns into the Ellwood Oil REfinery near Goleta. Although there were no casualties and little damage was done, the incident unnerved locals when told that it was the first attack of the war on the U.S. mainland. That February night, the all-clear signal for Ojai and the Central Coast didn’t come until almost dawn. The blackouts became a nightly occurrence thereafter, and it was several weeks before the standing order was rescinded and Ojaians resumed normal activities after nightfall.

Residents of Ojai, as in all American communities, threw themselves behind the war effort by raising money for the Red Cross, purchasing war bonds, rationing rubber tires, collecting scrap metal, nylon, and silk, sewing bandages and “comfort kits” for the wounded, even collecting cooking fat that was used to make munitions. “Everyone was involved in the war effort,” remembers lifetime Ojai resident Shirley Dunn Brown. She would soon leave Ventura College to work as a radio contact for the civilian fire and aircraft spotters at an observation post on the old Raymond Ranch near San Antonio School.

The Army Heads South

During February of 1942, a U.S. Army regiment of some 3,000 troops moved south along the California coast from Fort Ord, digging foxholes and patrolling several locations on the beaches until it reached Seaside Park in Ventura, where it established regimental headquarters in the winter of 1942.

Ventura resident Campbell Fahlman was a 26-year-old private from Nebraska serving with the 134th Infantry Regiment, a part of the 35th Infantry Division of the U.S. Army, that had been federalized by the Nebraska National Guard to help defend the California Coast. He remembers the temporary shelter at the fairgrounds vividly:

“We had no blankets or tents when we got there, so we slept on the stadium benches of the fairgrounds. It was cold and damp, and a lot of guys caught the flu. It was rough…”

The regiment’s 1st and 3rd battalions occupied “on line” positions on the beaches from Gaviota to Malibu, practicing “stand-to’s,” alerts, and patrols. Officers filled their intelligence journals with notations of alleged submarine sightings (which were later proven to be only sea lions) and mysterious lights reported along the blacked-out coast.

Camp “La We Ha Lis”

Meanwhile, Colonel Frank Dunkley was ordered to take the 2nd battalion inland as a reserve force. Seeking a location for the battalion’s training base, he discovered the Ojai Valley Country Club, which operated at that time as a winter resort. Ojai’s weekly newspaper then known as “The Ojai” reported that Army officers had visited the valley during the first week of May to scout locations for a “small unit” of soldiers.

“The telegrams flew back and forth from Ventura to Toledo, Ohio,” recalls Fahlman, as the Army sought permission from the Edward Drummond Libbey estate to occupy the private property. Three weeks later, a battalion of 1,000 men took over the former country club. “Everyone thought we were going to ‘O-jay,” remembers Bob Branch, a longtime Ojai resident who was then a young operations sergeant. “We were all from out of state, and we didn’t know how to pronounce the word, not even our commanding officer,” he chuckles.

A plea went out to Ojai homeowners with extra rooms or cottages to rent to make them available to the wives of soldiers who had followed their husbands to the new base. Many Ojai residents remember the influx of military visitors. David Mason’s grandmother’s house on Fox Street had a parlor that was diode into apartments for 4 army wives, and Shirley Dunn’s mother rented out rooms in their large family home in the Arbolada.

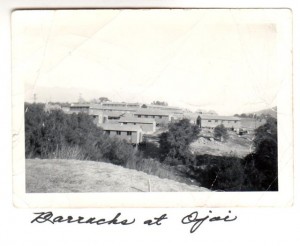

Military tents blossomed on the Country Club grounds. Enlisted men set up over 125 tents on the southwest side of the golf course, while some 20 line officers were housed in the clubhouse. Bob Branch remembers erecting the platform tents with wooden floors brought up from the Seaside Park headquarters: “It was a typical army tent camp with six enlisted guys in a tent. Each of the 4 companies first stationed there–E, F, G and H–had their own mess tent. Systems of open latrines–slit trenches–were dug into the golf course.” Wooden barracks were added a few months later.

The new camp was soon dubbed “Camp La We La His,” meaning “the strong, the brave” in the language of the Nebraska Pawnee, which was the 134th regimental motto. Roads were built between the barracks and the officer’s quarters and were respectively named Dunkley Road for the battalion commander, and Miltonberger Road for the regimental commander. Second Battalion Field in front of the clubhouse was designated the official parade ground, and the long, tree-shaded entrance road tot he former country club was renamed Nebraska Road in honor of the regiment’s home state. In time, the camp constructed a dispensary, a chapel, kitchens and recreation halls.

An officer’s club was set up in the clubhouse bar, which at that time was decorated like a British pub with tartan plaids and English prints on the walls. According to Shirley Dunn, who met and dated Army Capt. Rodney Brown while he was stationed there, “it was very cozy, very British-looking, and it just dazzled all those farm boys from the Midwest who had never seen anything like it!”

Romance and Pranks

More than a few couples recited their wedding vows before base chaplain Capt. John Reents, whose little daughter often stood in as a flower girl. Wedding receptions were held on the patio of the former clubhouse. Other romances bloomed between local women and the soldiers stationed in Ojai and led to weddings held out of state when the men were transferred to distant locations. Ojaian Shirley Dunn Married Capt. Brown in 1944. Bob Branch wed Norma Nichols of Ojai the same year, and Pvt. Fahlman married Madge Kilbourne, daughter of the newspaper’s editor, in 1943.

One night a young Betty Jo Buckner joined a group of her school friends who dared each other to sneak up the the Country Club “to spy on the Army.” Armed sentries stood guard every night at the three entrances to the property: at the intersection of Country Club Road and Country Club Drive, at the service entrance further south on Country Club Drive, and at the greens keeper’s house on Highway 33 and Ojai Avenue. The young pranksters managed to stay hidden from the rifle-toting guards, but by the time they got close enough to see anything interesting, their courage had disappeared and they ran back to town. Nevertheless, the life of a soldier must have impressed her, because two years later, Betty Jo Buckner became the first local woman to enlist when she joined the U.S. Air Force as a field locator and was stationed for the duration of the war at a bombardier training base in New Mexico.

Training and Readiness

While very little information was made public about the military activities inside Camp La We La His, those who were stationed there recall many days spent in combat training exercises in preparation for the expected enemy invasion. Whenever a Japanese submarine in the Pacific was lost on American radar screens, the 134th Infantry was put on alert. “They trained with 60- and 80-mm mortars, machine guns and rifles,” remembers Bill Bowie, a long time resident of Ojai and archivist at the Ojai Valley Museum. “At one time, I was a fire marshal; and I went along with the troops when they held artillery practice out by Rancho Matilija or up in the Sespe. My job was to report any brush fires that the ammunition might ignite.”

Pauline Emerson Farrar was fresh out of Nordhoff High School in the summer of 1942 and was working at Bill Bakers Bakery.

“We’d often look out the store windows to see small squadrons of armed soldiers sneaking through town from doorway to doorway, on special training maneuvers,” she remembers. “We had to remind ourselves that they were practicing military techniques for dodging enemy fire! Of course, we never interfered, but it always gave me a start!”

Pageantry and Parades

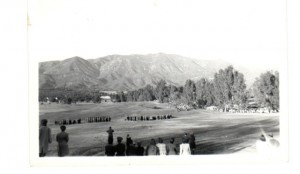

The regiment’s commanding officer, Col. Butler B. Miltonberger, a lover of military pomp and circumstance, quickly organized an unofficial regimental band. Â Private Campbell Fahlman joined as a drummer. Some 35 musicians, playing the drums, tubas, trumpets, trombones, saxophones and cymbals, were decked out every Sunday in white spats and dress belt and sash for the colonel’s formal Guard Mounts and Parade Retreats, marching in formation on the golf course in front of the flag pole. Ojai townspeople were invited to attend the ceremonies and remember the soldiers who were still dressed in their heavy winter uniforms in the middle of the summer. “The summer sun was brutal on those boys,” says Pauline Emerson Farrar. “There were always a few who would faint in the heat.”

Others remember the pageantry that stirred unabashed patriotism in the hearts of the local spectators. Writing at the time in a letter to the local editor, pastor George Marsh of the Presbyterian church described “the superb setting which suggests something of the grandeur and beauty of the far-flung expanse of our fair America–the green stretch of the beautiful golf links rising to the rolling hills which mounted to the noble range of the Matilija, and the mountains touched with the glory of the setting sun.” An officer in the camp was quoted as claiming, “No camp in the United States has a finer setting.”

Valley Hospitality Blooms

In town, a hospitality center serving coffee and doughnuts was opened for the soldiers at Russ and Ruth Brennan’s electrical shop on Signal Street, where the Dancers Studio is located today.

Villanova School made its pool available to the Army for swimming and diving, and softball games were organized at Sarzotti Park between the soldiers and local teams. Dances were held at Nordhoff High School (then located where Matilija Jr. High School stands today).

As a coed attending Ventura College in 1942, Harriet Grout Kennedy remembers “marvelous times” getting to know the soldiers who arrived in Ojai that spring. “The bowling alley was located at 312 E. Ojai Avenue where the Village shops are today, and we organized bowling leagues to include the Army boys,” she recalls. “We went to the movies at the Ojai Playhouse, and we also used to get out to the Maggie Hunt stables which were next to St. Joseph’s Hospital and take the officers on horseback rides.”

It wasn’t long before the community volunteers running the little hospitality center out of Brennan’s Electrical Shop moved their activities to the larger Jack Boyd Club, then located next to Libbey Park at the present site of the Bank of America [now Nomad Gallery], which became Ojai’s official U.S.O. headquarters. An Army dance band, formed out of the larger regimental band, practiced at the Boyd Club and played at the frequent dances held in the club’s basement, at the high school, or at other county U.S.O. locations. Campbell Fahlman, who played in the dance band, remembers those parties with special fondness. “I used to play the drums and watch this pretty girl who danced with all my buddies,” he recalls, “so I decided I’d better figure out a way to meet her.” He did, and married her a year later.

Military Secrecy

Recognizing “the importance of maintaining close understanding and high morale between the U.S. armed forces and the civilians among whom they are stationed,” Col Miltonberger assigned a Pvt. Gorfkle and a Sgt. Lorimer to submit occasional army news items to “The Ojai” for publication.

Although the exact number of troops stationed in Ojai was never revealed, nor were the destinations of the almost constant arrivals and departures of the various companies, military promotions were routinely reported, and community leaders active with the local Red Cross and U.S.O. were invited to the camp to discuss their volunteer projects with the officers. Col. Miltonberger was a stickler for discipline and insisted on the meticulous appearance of his troops at all times. The camp’s log records his almost-daily admonition to his officers: “Any member of this unit found dead in battle will be found properly dressed.”

Popular Guests

The troops were immensely popular with their Ojai hosts.

During December of 1942, locals teamed up to furnish two recreation halls on the base–one was was remodeled from the old garage building of the country club–by contributing a piano, tables and chairs, rugs and curtains, books and games, and had them both ready for use by the holidays, complete with fresh fruit and nuts. Trees provided by the Forest Service station in Ojai were decorated with paper chains and popcorn made by Ojai school children. Ojai churches sent their choirs to sing at the base chapel.

Rumors circulated that the 134th would soon get orders to overseas duty. Some 1,000 townspeople turned out to watch would be the regiment’s last ceremonial parade on January 10, 1943. Within days, “Ojai’s beloved Army group,” as one newspaper editor wrote, was abruptly pulled out in January 1943, leaving behind them an almost deserted camp, many local friendships, and not a few sweethearts. The soldiers of the 134th 2nd Battalion were sent to hot spots in both the European and Pacific theaters of war. Some were assigned to the Aleutian Islands, while most joined the ground divisions that ultimately merged with Patton’s Third Army in France.

During the eight months the 134th 2nd Battalion had been stationed at Camp La We La His, Ojai Red Cross volunteers had mended more than 2,000 uniforms for the soldiers,sewed military piping on 1,000 of their caps, and helped find rooms and employment for Army wives. Hospitalization and baby equipment were arranged for expectant Army mothers. Valleyites collected hundreds of rags that the soldiers used to care for their equipment, and gas heaters were donated to warm the wooden barracks during the winter months.

Camp Oak is Born

By May of 1943, a convoy of new Army units from the 174th Infantry arrived in Ojai from Fort Dix, New Jersey, with hundreds of raw recruits hailing from upstate New York. The promptly renamed their new home Camp Oak. The social schedule of popular U.S.O. dances and Army band concerts were resumed, along with the collection of donated furniture for the camp facilities. Sports events were played again at Sarzotti Park between the soldiers and local teams. The base’s new Army Chaplain, Lt. Frederick E. Thalmann, performed still more weddings at the officers’ club.

Much of the daily routine in Ojai again centered around the presence of the soldiers. Joe Sarzotti, whose family farmed many acres in the Ojai Valley, had been granted exempt status from the draft because his agricultural work was considered critical to the war effort. “I was just 20 years old when the war started,” he remembers, “and we worked from one season to the next harvesting barley, oats, citrus and about 40 acres of apricots. Almost every bit of it was sold off to the government’s quartermaster corps and wound up as C-rations. I don’t know why we had to bother with the middle man, we could have trucked it all to downtown Ojai and sold it directly to the soldiers at the Ojai Valley Inn.”

Joe did participate in at least a few bartering sessions that had a more perusal touch. Â He befriended several soldiers while they were stationed in Ojai, and they struck up a typical war-time deal: he swapped his much-coveted gasoline ration coupons for their cigarette coupons. Â “I was a smoker at the time, and those city boys said they definitely wanted to spend their precious leave time out of town!”

Not all the soldiers were so eager to leave the little quiet town. Â “There were more than a few romances that bloomed during the war years,” he says. “My sister Mary met a 1st lieutenant at a U.S.O. dance at the Boyd Club, and they dated for several months until he was shipped out. That’s the way it was during the war: here today, gone tomorrow.”

Sarzotti remembers several soldiers with the 174th Infantry from New York who used to make fun of the unglamorous life in the Ojai. “They thought it was the worst hick town they had ever seen!” he laughs, “but when they left, they cried. The people in Ojai were so nice to those young men, inviting them home for dinner, organizing social for them. I guess they weren’t used to that kind of warmth and hospitality.”

Here Come the Seabees

By the end of January 1944, the 174th Infantry had pulled out of Camp Oak and was assigned duties in Oregon, Arkansas, Oklahoma and Alabama. Life in town quieted down again, until word came that the U.S. Navy had allocated $80,000 to improve the camp for the Navy’s use. Seabees from Port Hueneme spent several weeks working on the barracks and the clubhouse and even adding two swimming pools.

In May 1944, units of the Acorn Assembly and Training Detachment from Port Hueneme moved in under the command of Capt. Marshall B. Gurney and Lt. Cmdr. Lloyd R. Saber. Like the Army soldiers before them, the sailors became an important part of Valley life, even spending their liberty time helping local ranchers with the harvest during the summer and fall. Ojai firefighters could always count on extra help during an emergency from the Camp Oak Navy personnel, and the high school football games were regularly attended by the Navy doctor and a pharmacist’s mate.

In November of 1944, when a commercial airstrip was approved for Ojai’s Dry Lake in Mira Monte (locally known as Henderson Field), the Navy loaned the heavy equipment that was used to grade the landing strip.

In April of 1945, locals were thrilled to be invited to Camp Oak to watch an exhibition match played on the camp’s 9-hole course by radio and film stars Bob Hope and Bing Crosby. Proceeds raised from the $1 tickets went to the Navy Relief Welfare Fund. Cmdr. Creighton, one of the Navy’s finest golfers, paired up with Bing Crosby, while Hope’s partner was Gabe Burbank, a former professional golfer who was stationed at Camp Oak at the time.

Some 3,000 spectators, civilians and servicemen alike watched the 12-hole match that was marked with the antics of the famous comedians. At the end, the Hope and Burbank team won the contest by the margin of one hole. It was an extravaganza of stars and military brass that focused enormous media attention on the little town and its former country club.

Victory Comes

Nine days later, on May 8, 1945, VE-Day was celebrated by all Americans, and three months after that VJ-Day brought an end to five years of combat on every continent of the world.

Still, it was months before the Navy at Camp Oak made known its intentions about its continued use of the property, although fewer and fewer sailors were seen in town. Rawson B. Harmon, local resident and manager of the Libbey interests in Ojai, announced that the Libbey estate would no longer keep the property but insisted that the Navy restore the links and the buildings to their original condition. Numerous private investor groups made offers to purchase the country club on the assumption that the military would son be gone.

But it was not until late summer of 1946, 15 months after the end of the war, that the U.S. government finally auctioned off over 50 barracks buildings and quonset huts, some of which were purchased by locals. Villanova School, which was facing an unusually high enrollment for its first postwar term, bought two large barracks to use as dormitories, and others can still be spotted in the Ojai Valley today as converted residences, workshops and places of business.

From Fort to Resort

In October 1946, the Navy returned the property to the Ojai Valley Company, and one week later Rawson Harmon, representing the Ojai Valley Company, announced the sale of the Ojai Valley Country Club to Don B. Burger, Willard Keith and Associates of Beverly Hills. An article in “The Ojai” assured locals that “Mr. Burger and his associates will operated the property in accordance with standards established by the Libbey interests and have expressed a sincere desire to cooperate in every way with the Ojai community in making the country club one of the finest developments of its kind in the country.”

Work on the reconstruction of the golf course began in December 1946 under the supervision of William P. Bell of Pasadena, the original architect of the famed course, and took seven months to complete. A new swimming pool was built, and tennis courts, stables and riding trails were completely reconditioned. Inside the charming old clubhouse, the dining room, bar, and guest rooms were restored by a team of local workers, including a recently discharged Army sergeant who knew the property better than anyone.

Campbell Fahlman had returned to Ojai, the hometown of his bride Madge Kilbourne, and drove straight to the country club where he had been stationed five years before he was sent to join Patton’s Third Army in Europe. Fahlman was hired on as part of the crew that worked on every inch of the 200-acre property throughout the winter and spring months; and on June 7, 1947, the former country club, that had been briefly known as Camp La We La His and Camp Oak, was officially reopened as the Ojai Valley Inn, leaving behind forever its place in the history of World War II.

Originally published in the Ojai Valley News.