The following article was printed in the Ojai Valley News probably in the 1960’s or 1970’s because that’s when the author (Ed Wenig) wrote for the newspaper. This article is reprinted here with the permission of the Ojai Valley News.

Ranger Bald was a man among men

An erect, elderly gentleman riding a spirited horse down Ojai Ave. to the post office was a familiar figure to residents of the valley in the 1940’s. Dismounting, he would swing into the post office on crutches, collect his mail, remount, and ride away to his apartment in the olive mill on the street that today bears his name.

Industrious, hard-working Geo. Bald come to the Ojai Valley in 1886 at the age of 22. He found his first job setting out orange trees for Edward Thacher on the land which is now known as the Topa Topa Ranch.

In 1891 George Bald married Miss Catherine Clark, the sister of the famous stagecoach driver, Tom Clark. The two went to the state of Washington to make their home for a decade. Returning to the Ojai Valley in 1900, Bald became operator of the Ojai olive mill, a new and promising industry. In the few years of its operation it was estimated that 11,000 gallons of oil were sold.

About 1902 George Bald decided to become a forest ranger. His headquarters were in Nordhoff, and his territory included the Ojai Valley, Sespe Hot Springs, Mutah, and Sespe Gorge to the Lockwood Valley.

Three trails

For the next 19 years he carved out trails on the steep mountain sides in winter and patrolled his area for fires in summer. Three well-known trails he built were the Topa Topa Trail, the Ocean View Trail, and the Pratt Trail. The last-mentioned trail was financed by Charles M. Pratt, Standard Oil executive who lived on North Foothill Road, at which point the trail began. Sometimes a trail 10 miles long had to be made to reach a place only two miles distant “as the crow flies”.

Fire-fighting, too was a strenuous job for Forest Ranger Bald in the days before the development of modern fire control apparatus and improved systems of communication. When fire or smoke was observed from his lookout or camp, he would tie onto his saddle a bag of barley for his horse, lunch for himself, his fire-fighting tools, which consisted of a rake, shovel, mattock and axe, and ride off to locate the trouble spot.

For these duties he received about $60 a month from which he was expected to purchase his provisions and clothing, and grain for his horse.

In 1921 George Bald was offered the superintendency of the biggest, and often called the best, orange grove in the valley — the very orchard he had helped plant in the eighties. For the next 15 years he devoted all his efforts to the well-known Topa Topa fruit ranch. When his wife died in 1936, and the Topa Topa ranch was sold in the same year, George Bald retired and went to live in an apartment in the old olive mill.

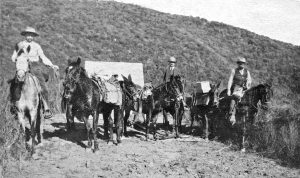

Ranger George Bald riding in the center in the back country.