The Meaning of Ojai Day, by Mark Lewis

Reprinted from The Ojai Quarterly

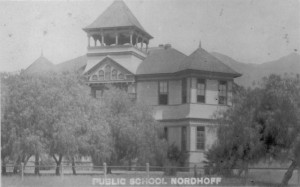

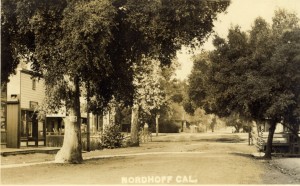

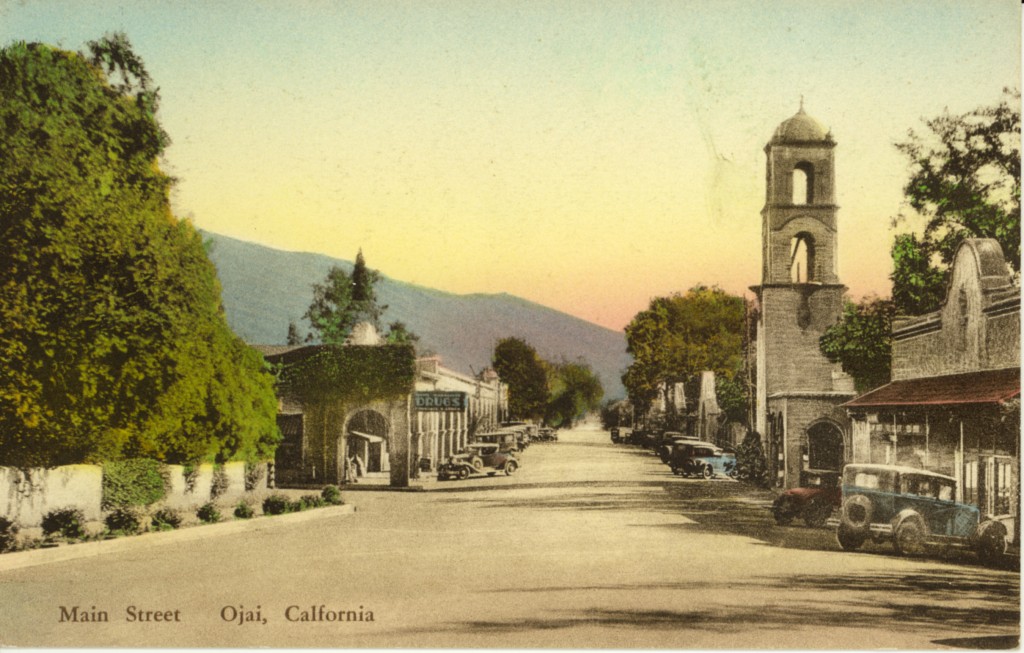

Downtown Ojai in 1920s. Courtesy Ojai Valley Museum

Ojai Day celebrates the 1917 transformation of Ojai from a dusty, ramshackle collection of old West shops into unified design of public architecture and parks, with converging perspectives of arches and towers. What inspired Edward Libbey to transform Ojai into an architectural jewel? Mark Lewis interviewed Craig Walker, who revived the Ojai Day celebration in 1991, for this in-depth look at the origins of Ojai Day. Craig traces the impetus to the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, an epochal event that launched the City Beautiful Movement, made Libbey a vast fortune and introduced him to Mission Revival architecture.

The original plan was to call it Libbey Day, to honor the man who had transformed the dusty, dowdy, backwater burg of Nordhoff into the model Mission Revival village of Ojai. But Edward Drummond Libbey was having none of it. He was proud of his role as Ojai’s guardian angel, but he preferred to celebrate the town itself on the occasion of its rechristening, rather than focus on his role in the process. As usual, Libbey got his way. And so, on April 7, 1917, some 2,000 people crammed themselves into the town’s brand-new Civic Park to celebrate Ojai Day.

“We are celebrating here today the fulfillment of a conception,” Libbey told the crowd. On every side stood examples of his handiwork: The Arcade, the Pergola and the Post Office Tower, all immaculately sheathed in sparkling white stucco or plaster.

“There has been too little attention paid to things aesthetic in our communities and in our homes,” Libbey said. “The time has come when we should encourage in ourselves thoughts of things beautiful, and the higher ideals which art encourages and promotes must awaken in the people the fostering of the love of that which is beautiful and inspiring. We must today decry with contempt and aversion all that is cheap, vulgar and degrading.”

That night the new buildings were illuminated with white light, rendering them incandescent. The effect must have reminded some onlookers of similar illuminations they had witnessed at the Panama-California Exposition, a world’s fair of sorts that had just closed on January 1, after a successful two-year run in San Diego’s Balboa Park.

Looking back at these events across a distance of 95 years, it seems clear that Libbey’s Ojai project was heavily influenced by the San Diego fair. The Panama-California Exposition had popularized the new Spanish Colonial Revival style, a baroque offshoot of the Mission style and Ojai’s Post Office Tower would have looked right at home in Balboa Park. But one local history maven, Craig Walker, traces Libbey’s original inspiration further back, to an earlier world’s fair: Chicago’s legendary World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, better known as the White City.

The Chicago fair had an enormous impact, and still lingers in the national memory. It is the subject of Erik Larson’s hugely popular nonfiction book The Devil in the White City, first published in 2004 and still going strong on the paperback bestseller lists almost a decade later. The book focuses on a serial killer, Dr. H.H. Holmes, the eponymous “Devil” of Larson’s title, who preyed upon fairgoers. But for most people who visited the White City, it looked more like heaven than hell.

It was there, on the shore of Lake Michigan, that Edward Libbey witnessed a testing of the hypothesis he would propagate in Ojai two decades later: that beautiful buildings inspire people to become better citizens. To judge by Chicago’s less-than-sterling reputation over the years as a bastion of civic virtue, the original experiment was rather a bust. Ojai would turn out to be a different story.

MAKE NO LITTLE PLANS

The World’s Columbian Exposition originally was scheduled to open in 1892, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus discovering the New World. But its organizers got carried away. Led by the architect Daniel Burnham, they turned the fair into an epic celebration of modern America and its apparently limitless potential. “Make no little plans,” Burnham famously said; “They have no magic to stir men’s blood, and probably themselves will not be realized.”

Big plans take time to develop. As a result, the fair did not open until May 1893. But it was worth the wait. Burnham & Co. had built an entire model city in Jackson Park. This was in effect a Hollywood set, made up of temporary buildings molded out of a kind of stucco and painted white to look like marble. Nevertheless, the effect was stunning especially at night, when they were bathed in electric light. Collectively they comprised the White City, and people looked upon them in wonder.

Some 27 million people visited the fair that year, the equivalent of a third of the country’s population. Among them was the future author L. Frank Baum, for whom the White City would serve as the model for the Emerald City in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Another onlooker was Elias Disney, a carpenter who had helped to build the White City; his son Walt would one day build his own White City in Anaheim and call it Disneyland. Even the notoriously cynical historian Henry Adams was impressed with what Burnham had wrought.

“Chicago in 1893 asked for the first time the question whether the American people knew where they were driving,” Adams later wrote. The answer was still unclear, but at least the question was framed intelligently. The White City, Adams wrote, “was the first expression of American thought as a unity; one must start there.”

All sorts of people beat a path to Chicago in 1893, including the theosophist Annie Besant, who was on her way from Britain to India. She stopped off in Chicago long enough to attend the fair’s Parliament of Religions, during which Swami Vivekananda introduced America (and the West in general) to Vedanta and yoga. Such epochal goings-on were routine at the Chicago World’s Fair, which also introduced America to the Ferris Wheel, Cracker Jack candy and Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer. But its most far-reaching legacy was the City Beautiful Movement, which the White City embodied.

“The industrial cities of the 1870s and ’80s had little planning “they evolved as crowded, ugly, haphazard affairs,” Craig Walker said. Burnham built the White City to show that there was a better way. “The belief was that cities built as a unified, planned development, with beautiful public buildings and parks, would inspire civic pride and moral virtues that would bring social reform,” Walker said. “The exposition was the blueprint for modern America; it had a major influence on art, architecture, city planning, business and industry.”

Ah yes, business and industry. The exposition was not entirely about art and moral uplift. Commerce also was highlighted, and many manufacturers built exhibits to showcase their wares. Among them was a certain glass manufacturer from Toledo, who saw the fair as his chance to hit the big time.

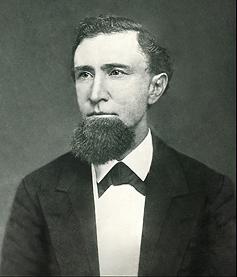

Edward Drummond Libbey was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts in 1854. He followed his father into the glass business and by 1892 was the head of Libbey Glass. The firm had moved in 1888 from New England to Ohio, where it struggled for a few years before finding its footing. Now Libbey saw the World’s Columbian Exposition as opportunity to establish his firm as the premier national brand for high-quality cut glass tableware. But his board of directors balked at investing big bucks to build a first-class exhibit. So Libbey borrowed the money himself and built it anyway. It was a full-scale glass factory situated on the Midway Plaisance, west of the fairgrounds proper. Libbey’s gamble paid off: The Libbey Glass pavilion was a huge success with fairgoers.

Libbey spent a lot of the time at the fair, living above the store, so to speak, in an apartment built into the pavilion’s second floor. The building was located half a mile east of the Ferris Wheel and just short walk west from Stony Island Avenue. On the other side of the avenue lay the shimmering White City.

Most of the fair’s buildings showcased the neo-classical Beaux Arts style, which America’s leading architects had studied in Paris. Among the more notable exceptions was the California Building, which stood less than a quarter of a mile away from the Libbey Glass exhibit. Paris had never seen its like. Nor had Chicago, for that matter. The California Building introduced America, and Edward Libbey, to a new architectural style called Mission Revival.

ENTER RAMONA

California had not always celebrated its Mission Era heritage. After the gold rush petered out, the state’s boosters needed to give people from back East a different reason to migrate west, and California’s Spanish and Mexican heritage did not seem like a selling point for white Protestant Americans. On the contrary, the state’s boosters feared that all those Spanish-style churches and forts made California seem too foreign and too Catholic. “From the 1840s to the early 1880s, the American immigrants did everything they could to eradicate the state’s Old World Spanish architecture,” Craig Walker said. “The missions and presidios were abandoned and destroyed.”

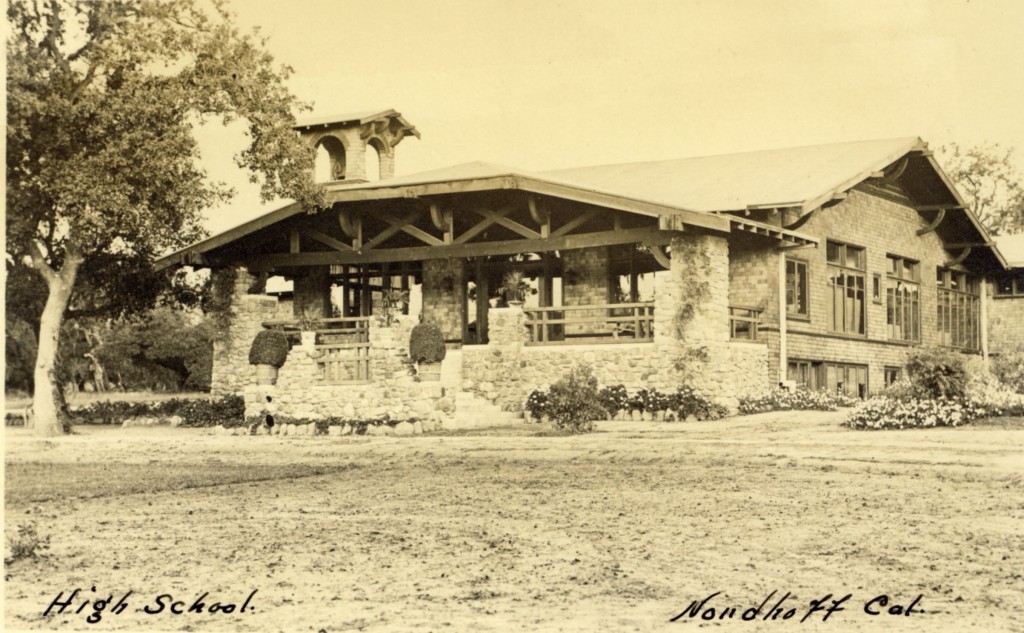

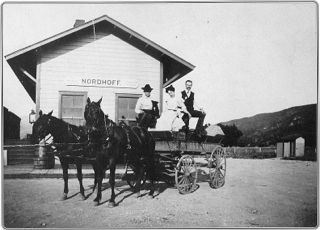

Casting about for a viable marketing angle, California’s railroad barons brought in the travel writer Charles Nordhoff to publicize the state’s natural beauty and healthy climate. Nordhoff hit the mark with his book California for Health, Pleasure and Residence (1872), an enormous success that induced thousands of Americans to move west. Some of them ended up in the sparsely Ojai Valley, where a real estate promoter named Royce Surdam was promoting a new town site. The settlers decided to name this town Nordhoff, to honor the man whose book had lured so many of them to California.

Nordhoff’s founders took no cues from the few remaining adobe structures they encountered in the vicinity. Their new town was built out of wood, and looked like it had been plucked from Kansas or Iowa and replanted in the Ojai Valley. But not every visitor from the East was averse to adobe. When the author Helen Hunt Jackson passed through Ventura County in 1882, she ignored Nordhoff but made a point of lingering in Rancho Camulo, a Spanish-style ranch near the present-day town of Piru. Rancho Camulo served Jackson as a model setting for Ramona (1884), her melodramatic novel about a young Indian woman who lives on a California ranch during the early years of statehood.

Ramona changed everything. A runaway bestseller, it sparked a national fascination with California’s Mission Era. The state’s boosters reversed course and embraced the old missions as iconic symbols of a romantic (and mostly spurious) past. “They just rode this Ramona thing,” Walker said. In the end, Jackson’s book lured even more people to California than Charles Nordhoff’s had.

Meanwhile, California architects concocted the Mission Revival style to create new buildings that harked back to the period in which Ramona was set. Naturally, when it came time to design a California exhibit building for the World’s Columbian Exposition, state officials chose a Mission Revival motif. The California Building was hardly the first example of this new style, but it was the first one to win nationwide acclaim. It made a big splash at the fair.

“It really was the building that got America’s attention,” Walker said.

Did it get Edward Libbey’s attention? He could hardly have missed it, given its close proximity to the Libbey Glass pavilion. Was he impressed? There is no way of knowing. All one can say with confidence is that Ojai’s future benefactor first encountered the Mission Revival style in Chicago in 1893.

The World’s Columbian Exposition also put Libbey on the path to extraordinary wealth, due to the success of his glass-making exhibit. “His whole glass empire just took off,” Walker said. “It propelled him to the top of America’s glass manufacturers, and he became one of the wealthiest businessmen in the country.”

And, crucially, the fair exposed Libbey to the full effect of the City Beautiful Movement. Before long he began applying its precepts to Toledo, where in 1901 he co-founded the Toledo Museum of Art. But Toledo turned out to be too big a city for one man to beautify. Libbey continued to support the museum, but he spent more and more of his time in Southern California. In 1908 he discovered Nordhoff, and built himself a winter home high up on Foothill Road. He loved the valley’s climate and mountain scenery, but was less impressed by its tacky architecture. Eventually, it occurred to him that Nordhoff, too, could benefit from the Libbey touch.

THE VILLAGE BEAUTIFUL MOVEMENT

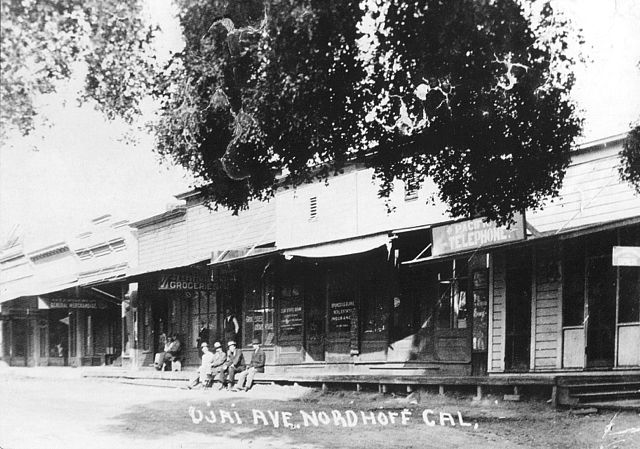

Nordhoff’s ramshackle business district did not amount to much: a forgettable stretch of uninspired wooden storefronts, indistinguishable from a thousand other hick towns languishing in the boondocks. In short, Nordhoff was homely. Libbey had a remedy. He had internalized the great lesson of Chicago, which was that art and human progress were inextricably linked. And among the arts, architecture was especially effective at creating a physical context for uplift. What had been true of Athens and Rome could become true of Nordhoff: Beautiful buildings would inspire civic virtue among the inhabitants, and make the town a better place in every sense. In April 1914, Libbey called a meeting of Nordoff’s leading citizens to offer a suggestion: They should essentially scrap the town they had, and build a new one.

“Make no little plans!” That was Daniel Burnham’s advice to the city planners of America, and it was Edward Libbey’s advice to the burghers of Nordhoff. His wildly ambitious proposal evidently stirred the blood of every man at that meeting, for they voted unanimously to embrace it. Why would they not, given that Libbey and his rich friends would provide most of the funds? And so the great experiment began.

There were still a few details to fill in. First and foremost, who would be Libbey’s architect, and what style would he employ? The choice ultimately fell upon Richard Requa of San Diego, whose firm, Mead and Requa, did some work for the Panama-California Exposition of 1915. Libbey evidently visited the San Diego fair, was impressed by its Spanish Colonial Revival motif, and hired Requa to create something similar in Nordhoff.

But the sequence of events suggests that Libbey already had settled on the Mission style for Nordhoff, well before he ever set foot in Balboa Park. After all, he had been familiar with the style at least since 1893, when he first clapped eyes on the California Building at the Chicago World’s Fair. And he no doubt had admired the Thacher School’s administration building, a Mission-style structure built in 1911. Significantly, the first major new building erected in Nordhoff in the immediate aftermath of that April 1914 meeting was a Mission-style movie theater, the Isis. (It’s still there, almost a century later, only now it’s called the Ojai Playhouse.) Given the town’s enthusiastic embrace of Libbey’s plan, it seems most unlikely that someone would have built a major new building in the downtown district without first vetting the design with the man from Toledo.

Libbey did have other architectural choices. The most impressive-looking building in downtown Nordhoff in 1914 was the Ojai State Bank, a stately brick pile in the neoclassical mode, complete with Doric columns. Theoretically, Libbey could have put up a neoclassical village to match the bank. But that would have looked bizarre, given the region’s historical context. The closest points of reference were Ventura and Santa Barbara, each of which dated back to the Mission Era and boasted an authentic mission building. Mission Revival was the obvious choice for Nordhoff. It seems likely that Libbey had made that decision even before he called that meeting.

Libbey of course was no architect. He left the design details to Requa, who used a mixture of Mission style (e.g., the Arcade) and Spanish Colonial Revival style (the Post Office Tower) to bring Libbey’s vision to life. Meanwhile, in March 1917, the town completed its Ramona makeover by changing its name to Ojai. Now it had a Spanish-sounding name to complement its new look. (The name, like the architecture, is not actually Spanish; it’s derived from the name of one of the Chumash Indian villages that once dotted the valley.) Thus it was Ojai Day, rather than Nordhoff Day, that the town celebrated a few weeks later on April 7.

At the opening ceremony, Libbey handed the deed to Civic Park to Sherman Day Thacher, who accepted it on behalf of the newly formed Ojai Civic Association. A reporter for The Ojai newspaper recorded Libbey’s speech, an earnest paean to the power of art:

“Art is but visualized idealism, and is expressed in all surroundings and conditions of society,” he told the crowd. “From the earliest age to the present time, art has been to the races of men one of the greatest incentives toward progress, refinement and the aesthetic missionary to the peoples of the world.”

Did the townspeople take Libbey seriously, with all his high-falutin’ rhetoric about Greece and Rome and beauty and virtue? Relatively few people in the crowd knew him well. He was only a part-time resident, after all. But clearly he was sincere, and most of his listeners were grateful that he had taken Ojai under his wing. Heads nodded in agreement as he launched into his peroration:

“Thus we are today celebrating, in the expression of this little example of Spanish architecture in Ojai Park, a culmination of an idea and the response to that spark of idealism which demands from us a resolution to cultivate, encourage and promote those things which go to make the beautiful in life, and bring to all happiness and pleasure.”

The crowd gave Libbey a huge ovation. And then the party began.

“Last Saturday a new epoch in the social and industrial life of the rejuvenated and resuscitated ancient Nordhoff, under a new title and new conditions, was ushered in and welcomed with joyous acclaim and much felicitation,” The Ojai reported in its next issue. “It was the most memorable day in the history of the Valley. New life, new ambitions and greater accomplishments will date from April 7, 1917.”

THE LIBBEY LEGACY

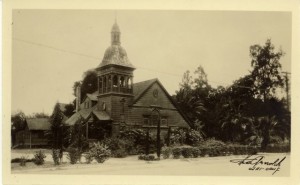

Ojai Day was not celebrated in 1918, due to America’s participation in World War I. But it returned in 1919 and became an annual event, as Libbey’s influence provided the town with more new buildings to celebrate: The St. Thomas Aquinas Chapel (now the Ojai Valley Museum) in 1918, the El Roblar Hotel (now the Oaks at Ojai) in 1920, the Ojai Valley School in 1923, the original Ojai Valley Inn clubhouse in 1924. Then Libbey died in 1925. The town continued to celebrate Ojai Day until at least 1928, but at some point after that, the tradition was abandoned.

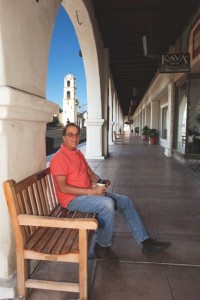

The buildings, of course, remained. But as the decades passed, some of them fell into disrepair. The original Pergola was demolished in 1971, the same year Civic Park was renamed Libbey Park. “And we almost lost the Arcade in 1989,” Walker said.

Walker is a retired Nordhoff High School history teacher and an expert on the valley’s architectural history. (He inherited some of that expertise from his late father, the noted architect and longtime Ojai resident Rodney Walker.) He was a member of the citizens group that saved the Arcade, by raising funds to refurbish it and bring it up to code. In the wake of that effort, Walker led a move to bring back Ojai Day. The event was revived in 1991, and now is celebrated each year on the third Saturday of October.

Walker also was among the people who brought back the Pergola in 1999. As a member of the Ojai Valley Museum board, he continues to lend his expertise to the museum’s projects. It was while researching a talk about Ojai architecture that Walker learned that Libbey had been an exhibitor at the World’s Columbian Exposition, where he would have been exposed to both the Mission Revival style and the City Beautiful Movement. Walker already was familiar with Libbey’s Ojai Day speech from 1917, but now he viewed those words in a new light.

“The words just echoed the real heart of what the City Beautiful Movement was all about,” Walker said. “On that day in 1917, the architectural and social ideals of the World’s Columbian Exposition were expressed in a beautiful new civic center that was created by a man who owed his own success in large part to that same Chicago exposition.”

Did Libbey achieve his dream for Ojai? Certainly his influence on the look of the town has been enormous. Walker points to all the beautiful Mission- or Spanish-style buildings that other people erected in the valley after Libbey worked his magic downtown. These include the Krotona Institute of Theosophy, Villanova Preparatory School, the Ojai Presbyterian Church, the Ojai Unified School District headquarters (formerly Ojai Elementary), the Chaparral Auditorium, and many, many others.

But an Ojai building need not be Mission style or Spanish style to reflect Libbey’s legacy; it need only be beautiful. Nor is his influence limited to architecture. Today the town is known as a mecca for artists, and Libbey, in a sense, was their prophet. He called for the community to pay more attention “to things aesthetic,” and his call has been heeded.

“It all goes to show, first of all, that one man can make a difference,” Walker said. “Libbey’s ideas must have infected the people of Ojai.”

In one way, Libbey outdid Daniel Burnham. The glorious White City burned down in 1894; only one of its buildings remains standing in Jackson Park. But Libbey’s buildings still stand along Ojai Avenue, and still perform their intended function. Burnham’s lost masterpiece was a blueprint for future cities that were never built, except, perhaps, by L. Frank Baum and Walt Disney. But the Emerald City is imaginary, and Disneyland is a theme park. Ojai is a real town, where people live. If today Ojai prides itself on its beauty and on its highly developed sense of civic virtue, then much of the credit must go to Edward Drummond Libbey, who set out to build a better town, and succeeded.

“I think it helped people realize that they live in someplace special,” Walker said. “This was Libbey’s stated intention “to inspire people to these higher ideals of civic involvement. One could say that his intention has been borne out.”

(Originally published in the Ojai Quarterly’s Fall 2012 issue. Republished with permission.)

(Originally published in the Ojai Quarterly’s Fall 2012 issue. Republished with permission.)