This article was originally printed on pages 42 – 46 in the December 1951 issue of “FORD TIMES” magazine which the “Ojai Valley Museum” has in their collection. The magazine was gifted to the museum by the Ojai Branch of the Ventura County Library System.

My Favorite Town —

OJAI, CALIFORNIA

by Lael Tucker

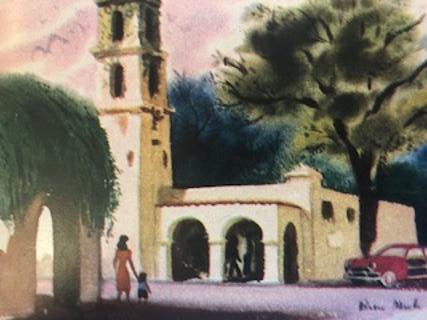

paintings by Brice Mack

We were looking for a temporary home town. We gave it that designation because, in the middle of a long trip, we had to find a town where we could spend six consecutive weeks writing. It had to be a very special kind of town—one to belong in—in a hurry.

We were rediscovering our own country after four years in Europe. Our own house was leased, our children in transition between languages and schools, our belongings scattered. So we started out to see our country again. Seventeen states and six thousand miles later, we were in Ojai, California.

Nobody told us about Ojai. We were still looking for that temporary home town. This day, we were merely on our way to relax in some hot sulphur springs up a small valley fifty miles north of Los Angeles. The narrow road from the Pacific Coast curled upward like lazy smoke. The gentle mountains on either side reminded us of the Pyrenees.

We came to a road sign that pointed to Ojai. We abandoned the hot springs idea simply because we like the name Ojai (O-hi), and because we felt happy. Six weeks later we still did. We hated to leave.

Ojai’s Main Streeet shops are sheltered in a long, homogeneous block under a continuous, graceful arcade. The post office has a Spanish bell tower, the park has picnic tables under the oaks and the best free tennis courts we ever saw.

The side streets are oak-shaded, and the Valley Outpost Motor Hotel is built on the edge of town under the mountains. Each housekeeping cabin is tree-shaded and private, and flowers bloom in each yard. The sun shines in a painter’s blue sky. Nights are cool in the brown, hot summer, and the winters are green and mild.

Ojai’s citizens come from everywhere, believe all kinds of things, dress as they like, and like what they please, from classical music to bowling at the local all-night short order joint. All kinds of school children go to all kinds of schools. The whole population—old settlers, winter residents, and visitors—have two things in common. They came to Ojai because they wanted to, and are there because they love it.

After so long in Europe, where everyone does everything for you, I had to learn to keep house all over again. In Ojai, everybody helped me do things for myself. Bewildered by the impersonal superabundance of food in the big markets, I went down the street to Mr. Cox’s family grocery. He helped me plan my menus and select the ingredients, while his chic, pretty wife told me how to cook what I bought. He also took me home in the store truck when I was walking, coaxed my daughter into drinking milk, and brought us orange crates for my son to convert to furniture. The Cox’s came from Oklahoma.

Since public laundering was rather an expensive business, Mrs. McNett, the manager of the motor hotel, loaned me her washing machine, taught me how to use it, and managed to do a big batch for me while showing me how. The McNetts are from Arkansas.

A lady from Maine initiated me into the art of making starch, and a neighbor from Louisiana said it was a pity not to darn good wool socks, and fixed up my husband’s while she demonstrated.

My husband wanted to write his book unmolested, do some walking in the country, hear some music and get a sunburn. Ojai obliged on all counts. Unlike the rest of California, Ojai expects you park your car now and then and take a walk for fun. It also understands a writer’s preoccupied, antisocial behavior. And there were six weeks of bright, browning sun—and a music festival!

El Rancho Ojai was a grant of land, full of streams, bears, wildcats and coyotes, all of which have since diminished. It was the press that really discovered Ojai’s dependable and lavish virtues. Charles Nordhoff, roving correspondent for the New York Herald, dropped up in 1872 and wrote so glowingly of climate and beauty that a lot of people named Dennison, Gray, Sinclair, Van Curen, Pirie, Montgomery, Munger, Waite, Todd, Pinkerton and Jones came out to visit and stayed to winter, founding a sunny, Spanish-style New England village in the western valley. In gratitude, they called it Nordhoff as well as Ojai for twenty-five years.

Its history is a fine mixture of New England and Wild West. A classical Latin scholar from Vermont named Buckman taught school in Ojai. One Colonel Wiggins opened the first hotel with a grand ball for three hundred and closed it again when his guests objected to being treated like company privates at New York prices. Four highly equipped professors, one specialist in Oriental languages, opened a Seminary for Young Ladies, but no young ladies dared the valley. The Thacher School for Boys, established in 1889, flourished, and later graduated author Thornton Wilder and Charles Nordhoff’s grandson, Charles, the writer.

Ojai town was incorporated in 1921 and has grown since from a population of 750 to 2,600. The constant sun, which is its blessing and its reason-to-be, has nearly destroyed it three times by making tinder of its surrounding forests.

But nothing has touched its spirit, its community spirit. Before you have been there a week, you find yourself partisan and citizen of Ojai. You speak of yourself in Ojai as “we.” It’s hard to define what makes it like that.

It’s a town of schools, day schools, boarding schools, progressive schools and prep schools, public schools and two where children take care of their own horses.

It’s a town of religions. Besides the usual denominations of an American community, there are Mormons, Missionary Baptists, and Four Squares. Mrs. Annie Besant tried producing the “new human type” in Ojai. Jiddu Krishnamurti made Ojai his retreat and many gentle people live there in order to listen to him.

It’s a town of the arts. It’s not its artists and writers, its Beatrice Wood, the ceramist, Guy Ignon, the painter, its Chekhov players or its music festival, that make it so. It’s everybody.

The millionaire’s wife will stand next to the talented plumber at the art exhibition. The wintering lady form Maine partners the Mexican ranch worker at the dance. The man who grows acres of oranges for fun or the one who drives in from Ojai to tend a business in Los Angeles may keep score for the school kids at the bowling alley. Whatever squabbles there are, are personal. You’re welcome. Not as a Howdy Stranger, but as Hello Citizen. They only want to keep Ojai the way it is: a place where you’d rather cut off your finger than cut down an oak tree and where you can belong at once, and for as long as you like.