The following article first appeared on the front page of the Wednesday, May 1, 1963 edition of “THE OJAI VALLEY NEWS”. It is reprinted here with their permission. The author is unknown.

TO PREVENT DISASTER

New firebreak shields valley

Ojai was partially swept by a brush fire in the 30’s and again in 1948. A project aimed at preventing repetition of such disasters is now underway in the mountains along the city’s northern boundary.

The project is a firebreak—or fuelbreak, as it is called by the U.S. forest service—to check any fires which might threaten the city.

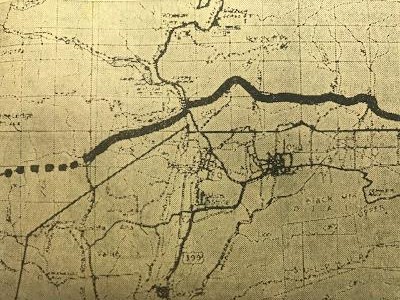

When completed, the fuelbreak will extend all the way across the county from the Santa Barbara to the Los Angeles county lines. A 16-mile section of the break from Santa Ana canyon, across highway 399 to the Topa Topa bluffs already has been completed. This includes the portion directly north of the city of Ojai.

A second four-mile section from San Cayetano to the Sespe along the southern border of the Sespe wildlife area also has been completed.

Portions from Santa Ana canyon to the Santa Barbara line, from Topa Topa bluffs to San Cayetano and from the Sespe crossing to the Los Angeles county line are still incomplete but work is proceeding on these sections. When the project is complete, it will form a continuous fuelbreak about 60 miles long.

The break consists of a strip of land cleared of brush for a maximum width of 500 feet where the terrain permits and a minimum width of 200 feet. Once cleared of the heavy brush the strip is seeded to rye grass and blando brome grass, hardy and fast growing varieties which require a minimum of moisture.

The object is to have the grass take over, providing a good cover and a minimum of fuel for a fire crossing the strip. The project provides for a continuous program of maintenance of the break, which includes keeping down the brush after it is removed.

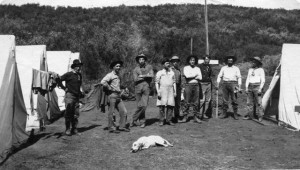

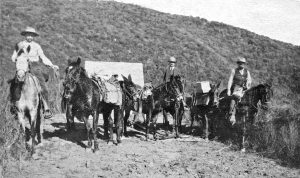

The work has been done by tractors and bulldozers in areas where these machines can work; in other areas such as canyons and gullies, the grubbing out has been done by men with hand tools.

The job has involved the gathering of large piles of brush. Some of this has been burned on favorable days. In other cases the brush has been shredded by tractors and worked into the soil of the fuelbreak.

The total area cleared is about 24 acres to a mile, but the brush has been cleared from about 384 acres in the 16 miles of fuelbreak already constructed.

North and east of Ojai many fingers and rectangles of privately owned land extend into Los Padres national forest, and in most cases north of the city the fuelbreak has been constructed across these lands. Forest service officials reported good cooperation from owners in getting their consent to build the break across their property. “We had to do some talking to get their consent in a few cases,” said Fred Bennett, Ojai district fire control officer, “but once they understood why we were doing it, and that it was for their own protection they were cooperative.”

The break has been constructed above the homes on these private lands to afford them the greatest protection. Another reason for crossing the private land was that the terrain becomes too steep to the north of these private holdings.

Chemical sprays and hand cutting will be the means used to keep down undesirable growth and permit the grass to take hold.

Deer have been of assistance in “maintaining” the break because they frequent the cleared area in considerable numbers and feed on the young shoots.

As part of the fire control program, water supplies in Gridley, Cozy Dell, Senior, Horn, Stewart and other canyons will be considered as available in case of need. It is also planned to develop other water storage together with access roads.

As an additional control factor, the fuelbreak has been planned to run as straight as possible considering the sometimes very rough terrain. Object of this is to allow borate bombers as straight runs as possible to spill their fire quenching chemical.

The project is a cooperative venture between the U.S. forest service and the county, with the county supplying the funds.

The break north of Ojai has been carefully planned to avoid a scar on the mountain which would be visible from the valley. The break in this area lies behind the geologic overturn—the row of small rounded hills which are such a conspicuous element of the northern view. The fuelbreak follows a swale or valley behind the hills and it cannot be seen from the valley except for a short distance at Gridley canyon and at highway 399.