The following article first appeared in the December 31, 1969 edition of “The Ojai Valley News” on the front page. It is reprinted here with their permission.

Review of the Sixties — Part 4

Freeway fighters win scenic highway battle

by Gary Hachadourian

(This is another in a series of articles reviewing the Sixties in the Ojai Valley.)

Early in the Decade the state legislature passed the Scenic Highway Act and then asked the counties which roads they wanted designated as “scenic highways.” Ventura county supervisors fingered Highway 150 from Santa Barbara to Santa Paula — through the Ojai valley — and that’s when the Battle of the Scenic Highway originated.

In the beginning, there was no opposition. In fact, if you had asked the average resident how he felt about Highway 150 as a “scenic highway,” the reply would probably have been “just fine.” It wasn’t until the state decided to choose the route that the first shots were fired and the battle joined.

The word “freeway”

In the beginning “scenic highway” had meant to the public, in essence, “making the highway more scenic.” When the state came forward with varied routes, residents soon learned that the new Highway 150 would be built according to “freeway standards.” The word “freeway” had alarming connotations and the issue at once became emotional. Few people wanted another freeway through the valley.

Between Ojai and Upper Ojai, four routes were being considered, the state announced. Though public sentiment was anti-construction, citizens early came to favor a route through Lion Canyon to the south of the city, away from the valley floor.

The Division of Highways had previously ceased to consider that route; but in what was seen as a partial victory for opponents of the highway, the state announced that it would re-study Lion Canyon, a more “expensive” route.

In May of 1967, however, at what was to become a turning point in the history of the battle, the newly formed Committee to Preserve the Ojai determined that it would actively oppose any selection of routes. In August of that year, the East Ojai Valley Associates, which up until then had been urging strict standards in construction made the same decision.

Throughout the next year, the Division of Highways persistently urged the city and county to agree on a route of its own accord and plan to set aside a “corridor of beauty” along that route in order to ensure that the scenic highway would indeed be scenic.

Huge petition

The City Council, in September of 1968, resolved that the Lion Canyon route was most desirable, a decision that sparked the Committee to Preserve the Ojai to get thousands of names in opposition on a petition.

When the all-important public meeting between state engineers and the aroused public came in October of 1968, the Committee to Preserve the Ojai presented a map of the valley on which each landowner who opposed all construction had his property colored red. Color the valley red.

The issue was not decided, however, until late 1969. At the urging of the City Council and the Board of Supervisors, the state agreed to postpone route adoption “for an indefinite period” in order to consider, first, “new priorities in valley road construction.”

The force of public opinion had triumphed.

There was irony in this “victory.” Opponents had been fighting to keep the valley rural by opposing the road. But it was the effects of urbanization that had brought the new road work priorities into existence and cause the state to lay off the scenic highway.

Traffic volume in the valley had grown to the point where, because freeway construction was falling behind schedule, the interim widening of Highway 33 between Foster Park and Ojai took precedence over the construction of any new road. More people in more cars needed to get in and out of the valley.

And the traffic volume within the City of Ojai had doubled. In December of 1967, City Manager Jack Blalock said that the city’s number one problem was traffic congestion in the downtown area.

In order to ease congestion, the city felt, the state should approve and construct a loop of two one-way streets in the downtown area along its state Highway 150 route.

And the loop was intended to solve not only traffic problems.

For, throughout the decade, another type of outside pressure on the valley had worked to force change within it. And though, in this case, the force was indirect, it was nonetheless real.

Ojai’s business community, with some exceptions, was suffering. As the decade progressed, the situation became increasingly pronounced to the point where, in 1968, despite population growth, taxable sales were the same as they were in 1964, this despite the fact that prices had gone up.

Promoting this situation was, of course, the development of new, convenient and competitive shopping centers in nearby cities, most notably in Ventura.

Absentee owners

Promoting it, also, was the fact that many owners of floor space in Ojai’s historic and distinctive shopping area, the Arcade, were absentee owners. They showed no inclination to spend money needed to refurbish their properties, even to the extent of making them structurally sound. (In 1966, an engineer opined that the Arcade could collapse in a severe earthquake.)

And the forces pressing for action became compounded in the latter half of the decade when the then unincorporated area along Maricopa Road to the west of the city quite clearly was being considered as a target site by commercial developers.

Also, in the untouched Santa Ana Valley a few miles away, county planners in 1967 approved plans for a 512-acre residential and golf course development that would include a new shopping center.

The traffic loop of two one-way streets in the downtown area was crucial to a plan to turn the tide. Getting the state to approve and construct a loop became the city’s number one priority. Thus, the Battle of the Scenic Highway was an ironic “victory” for Ojai.

The outrage was only reactionary, a response to the continuing force of urbanization.

If Ojai truly was to determine its future, the valley would have to anticipate events; would have to search its soul in an effort to decide what it wanted; would have to take steps to ensure that no unmanageable situations could even arise.

It would have to plan carefully, and completely, and stand by that plan.

Spelunking and other Vignettes from Drew’s Boyhood Days

The following article first appeared in the FALL 2021 (VOLUME 39 NUMBER 4) issue of “Ojai MAGAZINE”. The magazine was published by the “Ojai Valley News”. With their permission, the article is re-printed here.

LOOK BACK IN OJAI

with Drew Mashburn

Contributed on behalf of the

Ojai Valley Museum

Spelunking and other Vignettes from Drew’s Boyhood Days

Spelunking: There once was a tunnel that ran under the street in downtown Ojai by a creek bed. When I was a young teenager in the mid-1960’s, the tunnel ended behind a pharmacy in the Arcade. What made the tunnel a bit scary was the fact that it doglegs. Why was it scary you ask? Because my buddies and I would gingerly walk through it so as not to stumble over the rocks in the dark until the mid-way point where it bends. Back in those days, the dentist whose practice was next to it didn’t dig us kids using her stairs to get down to the creek. So, we had to be sorta stealth-like. Once we got to the tunnel’s midway point (the dogleg as we called it), light began appearing from the other end. But many times, just before we began to see the light, older teenage boys would be hiding in the darkness. As we approached they’d start screaming and scare the pee-waddin’ outta us! We’d take off runnin’ for the opening behind the Arcade, then scamper up the steep, weed-covered creek bank. Back then, there wasn’t an “Arcade Plaza.” In fact, the back of the Arcade was pretty sucky-looking. We didn’t care though, because we had just survived a cheap thrills adventure.

Read the rest of the article directly from the Ojai Magazine.

THE TRANSFORMATION HAS BEGUN

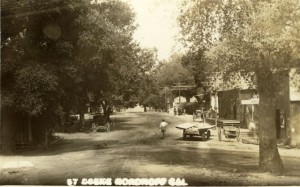

The following article first appeared on the front page of the Friday, August 18, 1916 edition of “THE OJAI.” The author is unknown. Note: Reference is made several times to the town of “Nordhoff.” This was what the town’s name was before it was changed to “Ojai”. All photos were added to this article by the Ojai Valley Museum.

THE TRANSFORMATION HAS BEGUN

Just now things are doing in Nordhoff of such unusual character that the oldest inhabitant is constrained to sit up, or stand up, and take notice. In fact, the activity is being led by one of the oldest inhabitants — Thomas Clark, who, indeed, throughout all the past in Nordhoff’s history, has lived an active life, contributing his full share of the warp and woof woven into history’s fabric, which has grown threadbare in spots by the constant wear of time, and which he has started in to rehabilitate with new industrial threads and some patches.

No doubt the inspiration for greater and better things first surged in on the crest of the wave of sentiment for good roads, becoming a fixed purpose when Mr. E. D. Libbey arose to the occasion and gave added impetus to the vehicle of progress not alone in words, but in action. As a captain of industry and commercial achievement few men are better equipped than Mr. Libbey. With the wealth to humor any reasonable ambition, coupled with an inclination favorable to this locality. Nordhoff is indeed fortunate to have the right to lay partial claim to the citizenship of such a magnanimous benefactor and admirer of nature’s gifts so lavishly, of which Nordhoff is the commercial center.

Mr. Clark’s labors for betterments are closely linked with Mr. Libbey’s plans for civic or community improvements, the work of the former aiding the purposes of the latter, which are known to and being carried out by Mr. H. T. Sinclair. Mr. Libbey’s confidential agent in the matter of improvements contemplated or in progress on the beautiful park tract and the old Ojai Inn square, which is the expansive front yard or plaza of the business center of Nordhoff, to be transformed into a place of greater beauty by the hand of artifice, and to harmonize the scene, without a blemish, the property owners will obscure unsightly fronts behind an ornamental arcade of concrete and tile, the material for which already lines either side of the street, awaiting the labors of the architect and the builders.

After some parleying, and a small amount of worry as to the fate of the postoffice, Tom Clark cleared the way for a place for the old postoffice building to light, and Escovedo, the housemover, accomplished the rest, and the old Smith building has been transplanted — in two sections — across the street, and now rests intact on the east side of the Clark lot, with post office, plumbing shop, barber shop and Brady’s kitchen safely housed as of yore.

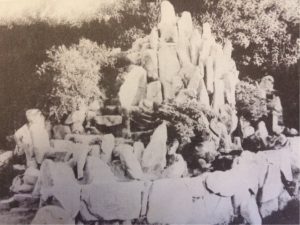

To do this Mr. Clark wisely revised his plans and demolished his entire barn structure, to be replaced with a modern garage and auto and horse livery annex. The west wall of the garage, under the skilled hand of Philip Scheidecker, of Los Angeles, is rapidly going up, entirely constructed of rock, mostly moss-covered, above the rougher foundation.

The removal of the old building is the signal for activity on the Libbey side, but just what transformation is to take place is a matter of rumor or conjecture. A fine building, without doubt, is to replace the old, combining post office and public library — perhaps. Many other things are likely to happen that will add to the greater and more beautiful Nordhoff.

Ojai was ‘torn apart and rebuilt’

This article first appeared in the August 26, 1970 edition of the Ojai Valley News. It is reprinted here with their permission. The author is Ed Wenig.

Ojai was ‘torn apart and rebuilt’

(Editor’s note: this is the second in a series of articles by historian Ed Wenig on Civic Center Park and the man responsible for its gift “to the people of the Ojai Valley” — Edward Libbey).

On September 1, 1916, THE OJAI printed an editorial from the Ventura Free Press, written by Editor D. J. Reese, who had attended the Men’s League Banquet in March at the Foothills Hotel:

“Some morning, not far distant, the village of Nordhoff is going to wake up and find itself famous. The work being done in that section just now would make the man who has known Nordhoff of old rub his eyes in astonishment if he was brought into the place suddenly. Great things are in store no doubt. The town has been torn apart and several sections have been removed hither and yon. There has been a general clearing up of everything, and everybody has an expectant look as though wondering what will happen next. The main street has been piled full of terra cotta brick, and no one seems to know what is doing. Old landmarks like the Clark stables and the Ojai Inn have vanished as before a Kansas cyclone. Only the beautiful oaks, and here and there a substantial house like the bank or the clubhouse or the Nordhoff fountain and splendid Ojai atmosphere seem to be left. Something is surely doing. Ask what it is and the Nordhoffite will throw up his hands and mention the name of Libbey. You hear about Libbey every time you ask a question. Everywhere you go you note that somebody is working hard at something or other in digging ditches or burying water pipe or clearing underbrush or building massive and magnificent cobble walls. Why, it is to be another Montecito, you are told . . . “The people there are to be congratulated that they have a Libbey who has taken an interest in their affairs. It is to be hoped they will give him free rein.”

Vast Land Holdings

At an Ojai Valley Men’s League banquet at the Foothills Hotel J. J. Burke, speaking of improvements, told of a well of Mr. Libbey’s which “will pump at least 65 inches, and if Mr. Libbey’s plans materialize he will spend $20,000 in getting the water to his ranch. . . . The old Ojai Inn and all but one of the Berry Villa buildings have been torn down or moved away, making room for more extensive improvements in the future. Through the generosity of Mr. Libbey, Signal Street was cut through and graded to the railroad.”

In the spring of 1916 Libbey was reported to be visiting his friend, H. T. Sinclair and discussing with Mr. Thacher, Colonel Wilson and W. W. Bristol “sundry matters of importance to the community.”

On June 9, 1916 it was announced that E. D. Libbey had bought 200 more acres to add to his previous 300-acre property. “Among the early improvements will be the laying of a water main from his well on the Gally tract to his large holdings. And that is not all, as the entire square upon which once stood the Ojai Inn, is to be improved in a manner that augurs well for the future of Nordhoff, which is good news to the entire community. Mr. H. T. Sinclair has been taken into Mr. Libbey’s confidence and will be the directing head during his absence. Let us be glad, as well as thankful for so generous a promoter as E. D. Libbey.”

On June 16, 1916, we are told that Mr. Libbey has bought the last parcel of privately owned land in what is now the Civic Park. In the local paper, “The plans Mr. Libbey is making to benefit both the town and the Valley has met with the highest approbation of the committee and the cooperation of the League in every way is assured.”

It was reported on June 30 that the Berry Villa, “an historical step-sister of the Ojai Inn, now a demolished antiquity,” had been torn down and the lumber hauled away.

By July 14, fifty men in one crew were working on the Libbey pay roll. Tom Clark destroyed his barn north of his livery stable and constructed a rock wall for a modern garage. This wall can still be seen as part of the Village Drug Store.

Early in November, Architect Requa, of the San Diego architectural firm of Mead and Requa, went to Toledo and got full approval of the plans for the renovation of the main street of Nordhoff. The local newspaper reported, “The post office tower, penetrating the lower heavens 65 feet is to be a reality. There are many features that we shall be delighted to prattle about when fully assured that the architect has removed the censorship.”

In March, 1917, representatives of the Men’s League met with Mr. Libbey. A corporation was formed under the name of THE OJAI CIVIC ASSOCIATION. The incorporators were E. D. Libbey, S. D. Thacher, J. J. Burke, Harrison Wilson, H. T. Sinclair, A. A. Garland, and H. R. Cole. Said the editor of the paper: “The initial purpose of the corporation is to assume title to the valuable property acquired by gift from Mr. Libbey . . . This beautiful park and the tennis courts, covering more than seven acres, is to become the property of the people of Nordhoff and the Ojai Valley.

Concurrent with the changes in the appearance of the town of Nordhoff came a popular move to change the name of the village to Ojai. A petition was circulated under the auspices of Supervisor Tom Clark requesting the name change, and received so many signatures that it was five feet long by the time H. D. Morse, manager of the Foothills Hotel, sent it to Washington D. C. In March, 1917, Senator James D. Phelan sent the following telegram: “You may announce the change of name from Nordhoff to Ojai.”

Garden Club Founded in ’26

The following story is from the “Ojai Valley New’s” OJAI GOLDEN ANNIVERSARY — 1921 to 1971 celebratory booklet. The story is reprinted here with the permission of the Ojai Valley News.

Garden Club Founded in ’26

The Fight to Preserve the Giant Native Oaks

by

Elizabeth Thacher

Every year the front inside page of the Garden Club yearbook has this line—“Founded in 1926 by Mrs. Frank Osgood.” The small group of women who started the Ojai Valley Garden Club were first of all gardeners. They wanted to know how to grow things in the Ojai and especially how to preserve the natives.

At the early meetings the members brought specimens to show each other and to discuss how best to cultivate them. They had speakers expert in their fields. One of the early speakers was Lockwood deForest, a landscape architect from Santa Barbara, who gave a series of lectures on what plants to grow in which part of the valley.

These pioneer members were the ecologists of their day, eager to preserve the beauty not only of Ojai Valley but also of all Ventura County. The Ojai Valley Garden Club was an outgrowth of a county wide garden club started in 1923. The original eleven members from Ojai have gone, except two—Mrs. Austen Pierpont and Mrs. Alfred Reimer.

Trees

The earliest minutes speak of preserving the oaks, sycamores and other trees native to Ojai—of the fights with county and city to prevent ruthless destruction of native growth to widen roads and highways.

One of the Club’s first projects was the planting of live oaks along West Ojai Avenue on both sides. These Memorial Trees honored first the unknown soldier killed during World War I, and then various Ojai persons whom we wished to honor. Club members did the planting, replanting when trees died, watering and battling those who craved their destruction to widen Ojai Avenue. Many of the trees still survive.

Creek Road winding among oaks and sycamores from Ojai to Arnaz Ranch has been preserved so far due to the Ojai Garden Club. The Club has a statement in writing from the Ventura County Board of Supervisors stating that no tree may be cut down along Creek Road without first contacting the Ojai Garden Club.

Memorial

Memorial Rock near the Bank of America [at the east end of the pergola in front of Libbey Park] was first suggested at a meeting in 1946. In 1947 the Ojai Lions Club set up the rock and asked the Garden Club to landscape around it. It did. A plaque bearing the names of the men who went from Ojai to fight in World War II was placed on the rock. In 1951 Austen Pierpont presented a plan for improving the memorial which the Garden Club accepted. It cashed its war bonds to put in a wall around the area and put in plants contributed by the members with their planting supervised by a Garden Club Committee.

Triangle

Where Highway 33 (then called 399) crossed route 150 at what is now the “Y”, there was a triangular piece of ground bare and unsightly. The Garden Club obtained permission to take over this property and plant on it trees, native shrubs and flowers. At first the county watered it. Later the Club took over this job, dragging hoses about then putting in a sprinkler system. It was hard work to keep things growing due to the adobe soil. When the roads were widened, the Y shopping center went in and a 3-way traffic signal established, the triangle became a victim of “progress”.

Post Office

Bulletin Board

In 1926 Mr. and Mrs. Austen Pierpont constructed and put up this board. Each month a Garden Club member is responsible for putting flowers in the three vases and notices of interest to gardeners and conservationists on the board. This project survives today [but in another form. Today it is a rectangle vase.]

Civic Plantings

One of the first plantings done by the then young Garden Club was to put in Matilija poppies and California poppies along Grand Avenue and in the crevices of the Japanese Fountain, which was built on the corner of Grand and McNeil Roads. Bulldozing to widen and straighten Grand destroyed forever both poppies and fountain.

A community Christmas tree was planted in Civic Center (now called Libbey Park). Trees, shrubs and plants were put around the tennis court area and in other parts of the park. The Garden Club is responsible for the planting in the patio constructed by Austen Pierpont. For many years the Garden Club paid the summer water bill of the Civic Center.

Shrubs, trees and flowers have been planted on the grounds of every public school in the valley by the Club—more than once. The Boyd Center, Soule Park and the Y have plants or trees supplied by the Ojai Garden Club. The latest project is the patio on the grounds of the Ojai Library—the interior wall, benches and plants all done by the Club.

Zoning

The Ojai Garden Club was one of the first to promote zoning and worked closely with the county and city zoning boards.

Signs

The redwood signs along the arcade were promoted by the Garden Club, which also prevented signs being put on top of the arcade—all but one, a rooster which flew up to his present perch where no one has been able to shoot him down. [No longer on top of the arcade, the author was referring to a neon sign in the shape of a rooster. It was installed by the first cocktail lounge in Ojai.]

Flower shows, sales of wreaths and decorating the arcade at Christmas have been club projects. This last is accomplished in cooperation with the Ojai Chamber of Commerce.

Folk dancing ‘all for fun’

The following article was written by Ed Nightingale for the “Ojai Valley News’s” OJAI GOLDEN ANNIVERSARY – 1921 TO 1971 celebratory booklet (page 10). It is reprinted here with the permission of the Ojai Valley News.

Folk dancing ‘all for fun’

by

Ed Nightingale

There were a lot of irate motorists in the Ojai Valley on May 11, 1946. The avenue had been blocked off in front of the arcade to accommodate a throng of strange looking people in odd costumes who had decided to hold the first folk dance festival in the state.

Naturally, nothing went right. The fire department had so watered down the street that nobody could stand up on it for well after the festivities were to begin. Then, the public address system failed to function. In the end, though, they had a jolly old time.

And that was the beginning of what has turned out to be one of the best biennial busts in the state of California. They come here by the thousands to participate or simply watch. It’s all for fun.

Spontaneous spirit

Early one morning, the Fire Department was serenaded in Serbian by certain parties from San Diego. Then there was a traffic jam on Ojai avenue in the small hours when Pasadena’s Tartan’s decided to present a Highland Fling in front of the Oaks Hotel. At the same time, a lonely piper from Santa Barbara was blowing his heart out in front of the Village Drug.

Under the leadership of people like David Young, Mary Williams, and Mary Nightingale, the Festival has always striven to obtain the finest exhibition groups in the state. It hasn’t failed. Such organizations as the Gandy Dancers, Cygany, and the Polish Youth Alliance keep coming back in their beautiful costumes because they like to perform here.

The Ojai Folk Dance Festival is held once every two years, usually in April or early May. The next festival will be in 1972. Looking back on 1946, and to cop somebody else’s words, the folk dance people say about the event, “You’ve come a long way, baby”.

Mary Nightingale

Dance Teacher

In the folk dancing field, Ojai boasts of having one of the number one teachers, Mary Nightingale. Mary has been associated with the Folk Dance Federation for the past 15 years and president of the Festivals since 1964. These Festivals are held in Ojai every two years—a fete that brings thousands of the interested from all over California. Her weekly classes are one of the most popular programs held at the Art Center. She has also taught in Ventura and Santa Barbara. With all this she still finds time to attend the Folk Dance Institutes in Santa Monica, San Jose, San Diego and Long Beach seeking newly imported dances from some small village to add to her repertoire. Mary’s very own favorites are the Scottish country dances from the land of her birth.

WHAT’S NEW DOWNTOWN?

The following story was printed in the book “Portrait of a Community (Ojai – Yesterdays and Todays)” by Ellen Malino James in 1984. It is reprinted here with the permission of publisher Ojai Valley News.

WHAT’S NEW DOWNTOWN [in 1984]?

By Ellen Malino James

When Edward Drummond Libbey started the Arcade in 1917, he agreed to share the cost of upgrading the front footage with Ojai merchants. Nobody considered the rear of the Arcade. While the street fronts of the Ojai Avenue stores were united by the Mission style of architects Mead and Requa’s original plan, the back doors stood for fifty years in a haphazard jumble of old wood shacks, some dating back to the original 1870’s town of Nordhoff. The front arches continued to grace the picture postcards, the Arcade having become a kind of façade, like a Hollywood set. Behind it, lay a deteriorating shambles of old Western clapboard buildings.

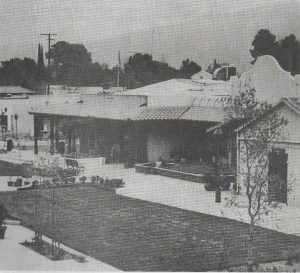

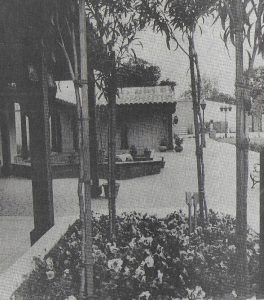

Architect Zelma Wilson and others foresaw that, with imagination and planning, the rear of the Arcade could become a “focal point of community life” – a village where residents and tourists alike could shop and socialize. The original plans of the Downtown Business Committee in 1971 called for plazas, fountains, covered walkways, and new shops and offices, all blending into a relaxed village atmosphere spanning the block from Signal to Montgomery Street behind the Arcade. Now, a decade later [1984], the Arcade Plaza is a local project, paid for without state or federal money. An ingenious application of the state law allowed for increased tax revenues within the redevelopment area to go exclusively for the benefit of this project.

When John Johnston came to Ojai as city manager in 1971, he recalls, “my great concern at that time was to prevent Ojai from turning into another San Fernando Valley.” Johnston, then in his late twenties, had just completed a term as City Manager of Artesia and Cerritos, where uncontrolled growth had transformed dairy farms into what was then the world’s largest indoor shopping mall.

“In Ojai,” says Johnston, “I ran into a city council that stopped this sort of development on its heels.” With Councilman Hal Mitrany and others, Johnston met with Ojai’s downtown merchants to explore ways to redevelop a “shambles” of old structures. In the back alley behind the Arcade, buildings were collapsing, Johnston recalls, “but what could we do? The city was too poor to do it on their own.”

AS A FIRST step, Johnston urged the city to form a parking and improvement district. The merchants then went to Architect Zelma Wilson, A.I.A. to design an expanded Arcade. Johnston then, in early 1972, asked Robert Hill of the California Department of Housing and Community Development to visit Ojai and to outline for the city council how the state redevelopment law could be applied specifically to Ojai’s needs.

Plans were laid for upgrading the downtown core and putting in public improvements with money from tax increments. Each time a property owner increased the value of his land and buildings within the 135-acre boundary of the agency, local tax money flowed into the coffers of the new redevelopment agency.

“So the project came out as originally hoped for,” said Johnston. “It just took a lot longer.” Ten years, in fact, from the original conception in 1972 to the dedication in April, 1982.

OJAI REMAINS one of the few towns to apply the state law on redevelopment in this novel and constructive way to its downtown area. The amount of money available to the redevelopment agency proved to be more than originally hoped for, because property values increased during the past decade beyond anybody’s wildest dreams. Yet with Proposition 13 and the inevitable decline in real estate values, the redevelopment agency idea is not as desirable as a tool as it once was.

Crucial to the redevelopment plan was the timing and local leadership in Ojai. “It is unlikely that the project would have taken place,” says Johnston, “if the interest and support were not there.”

Johnston particularly recalls the role of Clifford Hey and James Loebl: “When things got tough, they didn’t back down.” But there were many others. “Hundreds of people from all walks of life made this happen.” Just one example: Alan Rains invested in sidewalks outside his store long before the plans for the surrounding area took shape. What the redevelopment agency did was to create confidence in the community.

Behind the Arcade: Before

Behind the Arcade: After

Merchant Alan Rains recalls: “Our concern was that we did not want to see Ojai follow the same route as the San Fernando Valley with shops starting at Woodland Hills and running fifteen miles to wherever. Ojai had not been growing in a healthy pattern for several years and it was felt something needed to be done to revitalize the original shopping area.”

Photo: Girls Joyriding in Ojai

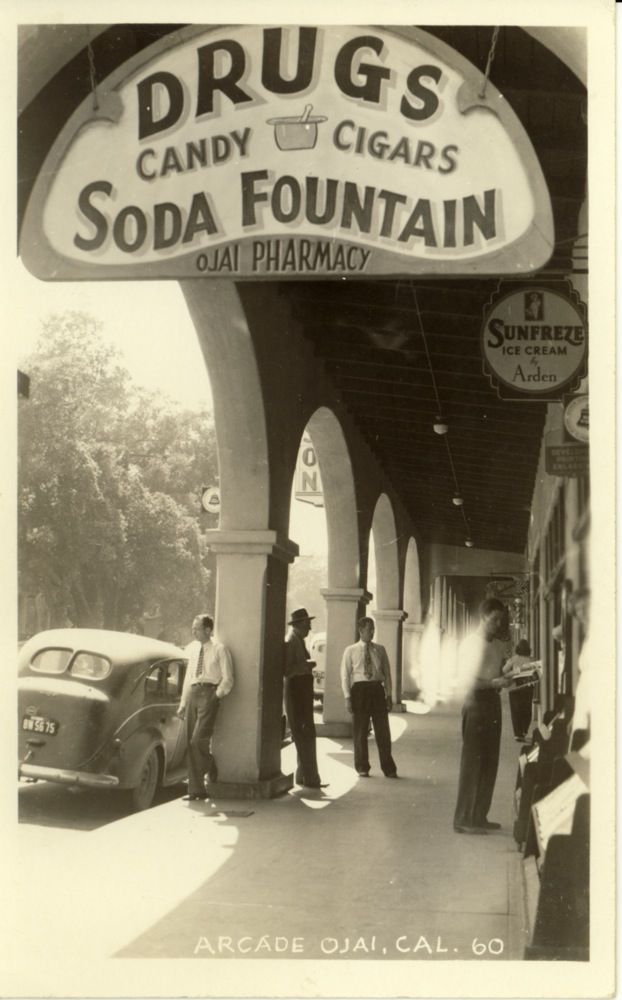

Postcard: The Ojai Pharmacy

The Ojai Pharmacy. Until the 1960s, the arcade was Ojai’s primary business district, catering to the everyday needs of local residents. One such business was the Ojai Pharmacy. In addition to filling prescriptions, it featured a full soda fountain and lunch counter. Howard Nelson Rockafellow, a colorful Ojai personality, started the business in 1927. Over the next 30 years he helped organize the Ventura River Municipal Water District, served as President of the Lions Club and Chamber of Commerce, and sat on the City Council. Rockafellow single-handedly thwarted a move by the Ventura Chamber of Commerce to rename Lake Casitas “Lake Ventura”. Ironically, while giving an autobiographical speech to the Retired Men’s club at age 71, he ended with, “I expect to live the rest of my life in Ojai”–only to be struck dead by a heart attack at that very moment.

The Ojai Pharmacy. Until the 1960s, the arcade was Ojai’s primary business district, catering to the everyday needs of local residents. One such business was the Ojai Pharmacy. In addition to filling prescriptions, it featured a full soda fountain and lunch counter. Howard Nelson Rockafellow, a colorful Ojai personality, started the business in 1927. Over the next 30 years he helped organize the Ventura River Municipal Water District, served as President of the Lions Club and Chamber of Commerce, and sat on the City Council. Rockafellow single-handedly thwarted a move by the Ventura Chamber of Commerce to rename Lake Casitas “Lake Ventura”. Ironically, while giving an autobiographical speech to the Retired Men’s club at age 71, he ended with, “I expect to live the rest of my life in Ojai”–only to be struck dead by a heart attack at that very moment.

The above is an excerpt from Ojai: A Postcard History, by Richard Hoye, Tom Moore, Craig Walker, and available at Ojai Valley Museum or at Amazon.com.

The above is an excerpt from Ojai: A Postcard History, by Richard Hoye, Tom Moore, Craig Walker, and available at Ojai Valley Museum or at Amazon.com.