The following story was printed in the book “Portrait of a Community (Ojai – Yesterdays and Todays)” by Ellen Malino James in 1984. It is reprinted here with the permission of publisher Ojai Valley News.

WHAT’S NEW DOWNTOWN [in 1984]?

By Ellen Malino James

When Edward Drummond Libbey started the Arcade in 1917, he agreed to share the cost of upgrading the front footage with Ojai merchants. Nobody considered the rear of the Arcade. While the street fronts of the Ojai Avenue stores were united by the Mission style of architects Mead and Requa’s original plan, the back doors stood for fifty years in a haphazard jumble of old wood shacks, some dating back to the original 1870’s town of Nordhoff. The front arches continued to grace the picture postcards, the Arcade having become a kind of façade, like a Hollywood set. Behind it, lay a deteriorating shambles of old Western clapboard buildings.

Architect Zelma Wilson and others foresaw that, with imagination and planning, the rear of the Arcade could become a “focal point of community life” – a village where residents and tourists alike could shop and socialize. The original plans of the Downtown Business Committee in 1971 called for plazas, fountains, covered walkways, and new shops and offices, all blending into a relaxed village atmosphere spanning the block from Signal to Montgomery Street behind the Arcade. Now, a decade later [1984], the Arcade Plaza is a local project, paid for without state or federal money. An ingenious application of the state law allowed for increased tax revenues within the redevelopment area to go exclusively for the benefit of this project.

When John Johnston came to Ojai as city manager in 1971, he recalls, “my great concern at that time was to prevent Ojai from turning into another San Fernando Valley.” Johnston, then in his late twenties, had just completed a term as City Manager of Artesia and Cerritos, where uncontrolled growth had transformed dairy farms into what was then the world’s largest indoor shopping mall.

“In Ojai,” says Johnston, “I ran into a city council that stopped this sort of development on its heels.” With Councilman Hal Mitrany and others, Johnston met with Ojai’s downtown merchants to explore ways to redevelop a “shambles” of old structures. In the back alley behind the Arcade, buildings were collapsing, Johnston recalls, “but what could we do? The city was too poor to do it on their own.”

AS A FIRST step, Johnston urged the city to form a parking and improvement district. The merchants then went to Architect Zelma Wilson, A.I.A. to design an expanded Arcade. Johnston then, in early 1972, asked Robert Hill of the California Department of Housing and Community Development to visit Ojai and to outline for the city council how the state redevelopment law could be applied specifically to Ojai’s needs.

Plans were laid for upgrading the downtown core and putting in public improvements with money from tax increments. Each time a property owner increased the value of his land and buildings within the 135-acre boundary of the agency, local tax money flowed into the coffers of the new redevelopment agency.

“So the project came out as originally hoped for,” said Johnston. “It just took a lot longer.” Ten years, in fact, from the original conception in 1972 to the dedication in April, 1982.

OJAI REMAINS one of the few towns to apply the state law on redevelopment in this novel and constructive way to its downtown area. The amount of money available to the redevelopment agency proved to be more than originally hoped for, because property values increased during the past decade beyond anybody’s wildest dreams. Yet with Proposition 13 and the inevitable decline in real estate values, the redevelopment agency idea is not as desirable as a tool as it once was.

Crucial to the redevelopment plan was the timing and local leadership in Ojai. “It is unlikely that the project would have taken place,” says Johnston, “if the interest and support were not there.”

Johnston particularly recalls the role of Clifford Hey and James Loebl: “When things got tough, they didn’t back down.” But there were many others. “Hundreds of people from all walks of life made this happen.” Just one example: Alan Rains invested in sidewalks outside his store long before the plans for the surrounding area took shape. What the redevelopment agency did was to create confidence in the community.

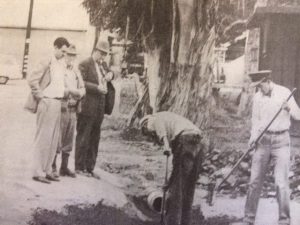

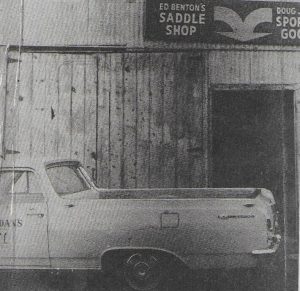

Behind the Arcade: Before

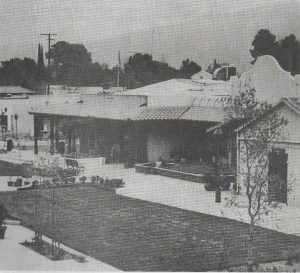

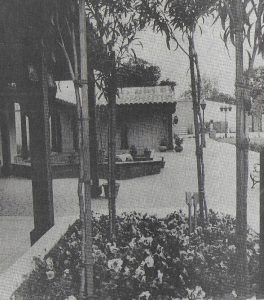

Behind the Arcade: After

Merchant Alan Rains recalls: “Our concern was that we did not want to see Ojai follow the same route as the San Fernando Valley with shops starting at Woodland Hills and running fifteen miles to wherever. Ojai had not been growing in a healthy pattern for several years and it was felt something needed to be done to revitalize the original shopping area.”