This article first appeared in the Ojai Valley News, but the date of the edition of the paper in which it appeared is unknown. It was written by Ed Wenig. Wenig wrote for the newspaper in the late 1960’s into the 1970’s.

The “iron horse” came to the valley in ’98

by

Ed Wenig

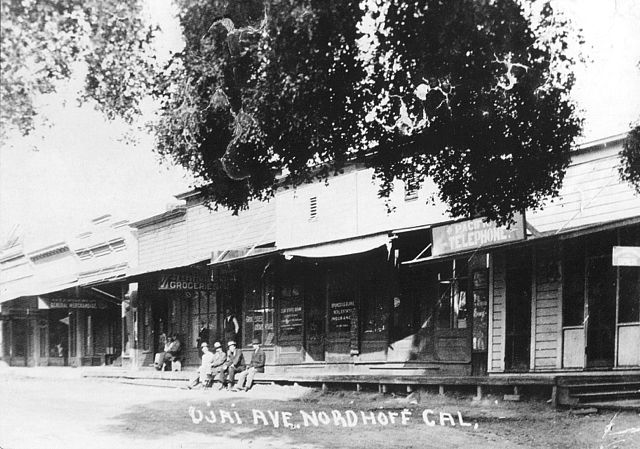

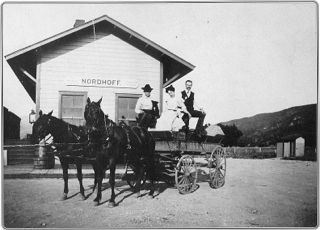

Two “iron horses” pulled four carloads of exscursionists into Nordhoff, as the band blared a welcome on a balmy spring morning of March 12, 1898. Ojai Valley residents, who had driven from far and near, in wagon, buggy and surrey, looked on with pride as official guests from Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, and neighboring Ventura County towns arrived on the first train ever to enter the Ojai Valley. Here indeed was concrete evidence of “progress” in its most up-to-date form.

The most important visitors were driven to the homes of prominent residents of the valley for luncheon, after which they were taken for brief scenic drives through the valley. But most of the passengers were loaded into surreys and wagons and taken to a picnic under the oaks in what is now the Civic Park [Libbey Park]. Then, the speeches began. Among them, one by W. C. Patterson, president of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, expressed thanks to the people of the Ojai Valley for having given “the outside world a chance to see and admire the beauty of the magnificent amphitheater of mountains which enclose this ideal spot.”

Health resort

In the Midwinter Edition of the Los Angeles Times appeared this comment: “This railway will open tourists to one of the most charming valleys in the state . . . With the advent of the railway, Nordhoff will possess all the requirements of a pleasure and health resort.” Imagine the pride of the residents of the valley when they read in the Ventura County Directory, “The valley has been settled by a superior class of people, intelligent, refined, and very enterprising. Many of them have abundent means and have been men of standing and influence in other communities.”

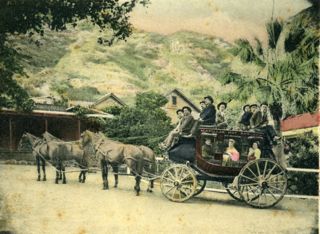

There were four passenger pickup stations on the railroad between Ventura and Nordhoff. Starting from Ventura they were Weldon, Las Cross, Tico, Grant, and finally the Nordhoff Station. In the first few weeks after the opening there were two trains daily, after which a schedule of one train per day was established. In response to repeated requests from J. J. Burke, the Southern Pacific re-established a schedule of two daily trains for the winter months only. Trains left Nordhoff at 7:20 a.m. and 4 p.m. for Ventura. Returning trains arrived in Nordhoff at 1 p.m. and 8:15 p.m. Passengers bound for Matilija Hot Springs disembarked at Grant Station located approximately at the present lumber yard at the “Y” [Rotary Park now]. From there they went by stagecoach, and, in later years, by Stanley Steamer to Matilija.

It took 10 years

The arrival of the first train was the culmination of ten years of hopes and planning. In 1891, under the headline “Railroad Coming” a writer for THE OJAI observed, “Soon the invalid or tourist can recline in his upholstered seat within the observation car and be whirled over hill and vale to his destination, instead of a tedious ride in a stagecoach.” At first a Ventura company had been formed to build a narrow gauge railroad. But Captain John Cross proposed to build a standard gauge road, and with the enthusiastic cooperation of the businessmen of the Ojai Valley was successful in bringing the dream to reality.

When automobiles came into more general use the importance of the railway passenger service declined, and in later days the line was used entirely for shipments of freight.

Since the flood of 1969, which washed out portions of the road bed, the railroad has been abandoned. [Today it is the Ojai Valley Trail.]