The following article first appeared in the Sunday, December 28, 1969 edition of “THE OJAI VALLEY NEWS” on the front page. The article is reprinted here with their permission.

Review of the Sixties — Part 3

Urbanization — the story of the decade

In this, the third of a series of articles reviewing what happened in the Ojai Valley during the Sixties, reporter Gary Hachadourian takes a close look at the causes and effects of urbanization on the once-rural valley. “Urbanization” is the hallmark of the past decade, according to reporter Hachadourian, who spent months scanning the front pages of the Ojai Valley News of the years 1960–1970.

by Gary Hachadourian

The urbanization of the Ojai Valley was forced upon it — forced in three ways:

By pressure from outside the valley;

By pressure from within it, generated to ensure that growth would be ordered along predetermined lines, rather than haphazard.

And, once urbanization began, it was forced by the “system” and by the power of the valley’s “personality.”

These forces were not isolated one from another; there was no strictly sequential order in which they made themselves felt. They coexisted.

But the forces of urbanization here did make themselves felt, for the first time at least, in roughly a sequence. So, for the purpose of simplifying this article, they probably should be handled that way.

From outside

First, then, the forces exerted on the valley from outside it.

They ranged from the vague and unnerving thought that the golden Southland was growing and would soon need more space in which to grow, to the very specific and community-rallying force exerted by the state as it went ahead with plans to construct, first a freeway and then a scenic highway along the valley’s floor.

In 1960, a study reported that the population of Ventura County, set then at just under 200,000 would double within 20 years. The report named Ojai as a target area for residential development and said that the valley’s recreational areas would lure many vacationers.

(As it turned out, that report was modest. For the county’s population has almost doubled in ten years rather than twenty.)

In 1962, a professional firm doing a land-use study for the county forecast that the population of the Ojai Valley, in fact, would more than double in 20 years. This firm, which had also been commissioned by the City of Ojai to draft a general plan for development, said valley population would jump from its current level of about 15,000 up to 40,000 by 1985. Later forecasts would predict even greater jumps.

(As of this year, population of the valley from Casitas Springs to Upper Ojai has risen since 1960, to just under 22,000.)

A person who lived in Ojai during these early years of the decade might have doubted the actual figures in these reports if he had wanted to; but there was no way for him conscientiously to deny the forecast of growth.

County growth

The county was developing rapidly during these years. Most of the development was (and is now) taking place in the southwestern part of the county, in those areas closest to Los Angeles. But it was occurring also in Ventura and Oxnard. More significantly, it was primarily commercial and industrial development that was going on in this, the coastal area.

But, in the valley, it was seldom pressure exerted for the expansion of industry. County and state officials and private developers certainly realized already (though not to the extent they one day would realize) that the valley would not readily accept any development that clearly might damage the area’s looks or threaten its cleanliness.

Besides (and perhaps more importantly), it is the nature of successful developers that they know what uses can be sold to a community for a given piece of land.

So the pressure on Ojai was not for industrial expansion. Predictably, and true to the forecasts, it was for residential development.

And what was learned by valleyites as the proposals for various subdivisions came in was that many developers, while they obviously agreed that the Ojai should be developed residentially if at all, had their own ideas about the location, type and density of housing that was desirable.

In many instances, also, county government bodies had ideas, that differed from Ojai’s.

Proposals came into the county or the City of Ojai for cluster-housing developments such as apartment buildings, trailer parks and condominiums, in addition to the more standard (and, for valleyites, more acceptable) tract subdivisions.

And what was built was bought as people settled on the valley as a place to retire to, or as a place in which to escape the haphazard and oppressive development of metropolitan areas and find joy again in nature, or as a place, quite simply, which was close enough to the office in Ventura and had available housing.

Action in the county

Of the two types of proposals — those for developments either within the City of Ojai or on unincorporated territory — the more important ones, were those for county land.

(Ultimately, the developments that were proposed and carried out within the city had, and will have, greater impact on the long-range future of the valley. But that is another story. The proposed county developments were more significant at the beginning of the decade.)

The proposals for the development of unincorporated land forced the city to look about itself; forced a renewed realization that what happened in any part of the valley affected the whole of it.

Therefore, the City of Ojai joined residents of the outlying areas in their concern when, for instance: the 121-acre G-Z Ranch was sold for possible industrial development in 1962; when a 40-acre, 356-unit mobile home park was planned for the south slope of Krotona hill in 1964; when a $3 million subdivision of 38 homes was proposed for the Dennison Grade in 1966.

These developments were seen as undesirable by Ojaians. County supervisors, though, were not so partisan. Ultimately, the developments were not carried out because: in the case of the G-Z Ranch, plans were never presented (the area now, however, is being considered as a site for a mobile home park); in the case of the Krotona mobile home park, supervisors refused a permit; and in the case of the Dennison tract, supervisors placed what amounted to economically prohibitive conditions on the use permit.

Supervisors were not without political motivations in arriving at their decisions. One factor in their decision-making was the public interest in the issues shown by Ojaians.

Valley-ites had discovered a weapon they could use to fight unwanted developments.

It was a weapon that would be used many times during the decade — force met with force, the complexities of back-room politics met with the straightforward simplicity (and sometimes, the simplistics) of an indignant populace, the nebulous but undeniable pressure for change met with the rage of frustrated, and bitter protectionist citizenry.

The fact that public outrage was quite often a negative weapon — negative in the sense that it was nothing other than reactionary — seemed to go unnoticed by many people. Public demonstrations were (and are) justified as the people forcing an unresponsive and sometimes devious government to respond to the public’s desires to preserve Ojai. Partly, they were that. But partly, too, they were an expression of a conscience that knows it has waited too long before speaking out; and an expression of frustrated isolationism.

But if public outrage was sometimes negative, it was also, at times, positive — to the extent that no other course of action was available to the people.

And the best examples of relatively positive outrage were the Battle for the freeway and six years later, the Battle of the scenic highway.

Both battles, of course, were centered around the desirability of having a major highway running along the valley’s floor in the area of Ojai. But the battles differed insofar as the sensitivity of the opponent was concerned — his sensitivity to the feelings and the do-or-die dedication of the valley-ites. (The proponent, naturally, was the state.)

There’s been a change

During the Battle for the Freeway, the state’s champion, the Division of Highways, was as insensitive in his proposal as he was intractable in his stand—at first.

Six years later, however, the Division of Highways showed considerably more restraint, more willingness to compromise, as it pushed for the adoption of a mutually agreeable route for a scenic highway. In fact, it urged the City of Ojai to protect itself by planning a “corridor of beauty” for the route.

(Late in 1969, the Div. of Highways’ handling of Ojai would finally be directly opposite to what is was earlier. The division would request the city to hold a public hearing on the proposed traffic loop in the downtown area before—before—the state arrived at a recommended route. This so that the state could know the feelings of Ojaians before they spent the time and money on possibly objectionable route studies.)

Residents of the valley, however, showed no such inclination toward large compromise in the scenic highway issue. Their determination was as steadfast, their views as adamant, as they had been when the freeway was discussed.

The frustration and even anger of highway commissioners was apparently complete when valleyites reared up at them this second time, over the scenic highway; for, from their point of view, they were pressing only for a type of highway which the valley had determined years before was acceptable.

In the Battle for the Freeway, then, it was nothing less than the State of California that was the force pressing on the valley from the outside for change.

The Division of Highways, with its tendency to see beauty as a straight line between two points, saw the need for a freeway to Los Angeles by way of an inland route. The valley’s floor was not only a conveniently flat roadbed; it was also the route indicated in the state’s master plan for highway development.

This plan, the state’s engineers explained, was drawn with an eye toward the future needs of the target area (i.e., its projected population growth) as well as with an eye toward convenient traffic flow throughout the state.

It would be a freeway to serve anticipated needs. But since a freeway promotes development in addition to serving it, the valley was, inevitably, to be “opened up.”

There was never any question about whether it would be built. The state had its prerogatives, after all. The battle was over the route it would follow.

The Division of Highways, to the amazement of Ojaians, believed that it should pass through the City of Ojai. In 1960, residents viewed posted drawings that showed no less than 15 alternate routes through the city, some of them along Ojai Ave through the downtown area.

It is an understatement to say that residents’ feelings ran high.

The Ojai City Council, under the leadership of Mayor Robert Lagomarsino (now State Senator) was urged to protest. Certainly, the council would have done so of its own accord.

Of the many alternatives proposed by the state, the majority of Ojai citizens, recognizing that some route would be adopted, favored a route to the south of the city, along Creek Rd. Next in preference was the Ventura River bed route through Meiners Oaks.

It was this second alternate that the council urged the state, saying that a freeway was not needed through Ojai.

The public was quick to sign a petition that endorsed the council’s resolution.

On September 1, 1960, residents turned out in force for a meeting of state engineers and the public at Matilija Junior High. Engineers were insistent that the projected traffic volume of the city made a city route necessary. The audience disagreed.

No decision was made, of course, and residents left the meeting with the disturbing feeling that the state might not respond to their desires.

River route

Subsequently, the council formed a Freeway Study Group of selected citizens with the aim of providing the state with a more thoroughly considered opinion from Ojai residents. This group, too, recommended the river route after two months of study.

In May of 1961, the state announced that it would delay route adoption in order to give it more thought.

And a year later, in May of 1962, the state opted for the river route. (In addition to being the route desired by valley residents, it was also the cheapest.)

Residents were elated. In a figurative sense, at least, handshakes were passed all around, congratulatory.

Public sentiment clearly was a weapon that could be used to determine the future.

Somewhat determine it. The city was left intact, but the freeway, nevertheless, was now a reality. And the freeway, as a force, would promote an urbanized valley at least as much as it served it.

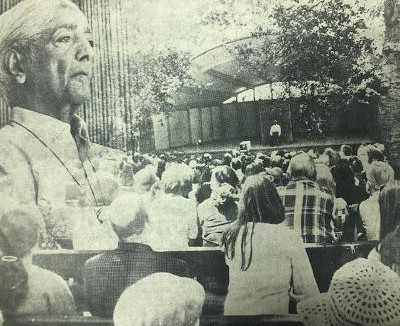

Interview with Krishnamurti about the Ojai Valley

The following article first appeared in the April 12, 1972 edition of the “Ojai Valley News” on page D6. It is reprinted here with their permission.

Editorial by Fred Volz

Rare conversation with Krishnamurti about the Ojai Valley

Last week our long-standing request to interview Jiddu Krishnamurti, world renowned philosopher, was granted. We spent almost two hours taping this interview, mostly about the Ojai Valley. Krishnamurti is now in New York City to give two talks at Carneigie Hall, before returning to England.

Krishnamurti is a slight, aethetic man with golden skin and large, soft brown eyes. He speaks with an Oxford accent in muted tones, pausing occasionally to collect his words.

He was born in 1895 in Madras, India, the eighth child of a Brahmin family. At 16, with his brother Nityananda, he was brought to England where he was privately educated. He first came here with his brother in the ‘20’s, and we begin our interview with that.

The conversation is almost an exact replica of our tape recording.

Sir, I feel that the people here would appreciate your views about the valley. May I ask you some questions about Ojai?

Krishnamurti—Yes.

Volz—You came here many years ago and you’ve stayed here from time to time. What are your personal feelings about the valley?

K—I came here first with my brother in 1922. We lived here. We came from India via Australia and lived in a little cottage. And the contrast was enormous. We came in July. The dryness, the heat, the dust. But we liked it enormously. It was the mountains. I’ve been practically all over those mountains, over all these trails. I’ve been up to Topa Topa, up to Chief. And I stayed here during the war . . . and off and on . . . treating this area as kind of my home. I also go to India, that is also my home. I stay in England—but this is one of the most beautiful valleys I’ve seen. I’ve been to Kashmir, and I’ve been to Switzerland, and parts of Europe . . . Pyrenees and various mountains in India. This has an extraordinary charm that the others do not have. It’s extraordinarily quiet at night. Wild. And I used to see deer up there . . . bear. Once, I walked behind a bobcat for several miles. The wind was blowing from him to me. So he didn’t smell me at all. Several miles . . . he was rubbing himself and enjoying himself. I don’t know whether they exist now.

V—Rare. Only very occasionally do I see one . . . just a flash.

K—And I see raccoons, foxes, and I’ve seen several times big brown bear. Marvelous. And somehow I like this place enormously. But I see it gradually being spoiled. I hear they want to put a highway through here. That’s the end of this valley. And they want to develop parts of it . . . a tourist resort and all that. I suppose this is what is really happening all over the world. When there’s a beautiful spot, they want to destroy it . . . exploit it touristically for economic purposes. I know a place in India, a beautiful place, but it’s spoiled now by overpopulation. Get rich quick. Recently, I stayed as a guest in Malibu and they’re destroying that whole hill. Terrible.

V—Well, you’ve answered the first three questions I have. I was going to say you saw Ojai then . . . and you see what’s happening now. I was also going to ask you what exceptional qualities Ojai had in the twenties and what it does not have now.

K—This East end has still got it. Because I can go up one of those hills and not see anyone. In those days I would go . . . oh . . . miles and miles . . . but now it’s gradually being pushed out. It will be destroyed. Unless you all stand firm.

V—Do you see any change in the way it’s going now. Or is gradually the land being used up?

K—I’m afraid so.

V—You don’t see a change. Is there anything we could do about this?

K—Ah, I suppose . . . I don’t know why the government . . . or people congregate . . . and say this is one place in California that should be kept the way it was. Or it will be completely wiped out.

V—As a result of economic motives?

K—The way we are going now in America . . . and the rest of the world . . . in 70 years through overpopulation man will destroy himself.

V—There have been encouraging things happening here recently. For example, the Meditation Group—the private schools . . . Happy Valley, Ojai Valley, and Villanova. So there has been a move in that direction. People coming here to build schools and have them expand. Do you see anything happening here along those lines?

K—Let me tell you about Happy Valley. We came here in 1922. In 1927, Dr. Besant . . . the Happy Valley Foundation . . . she started it . . . she bought land, mortgages and all that. She bought it for one purpose . . . I don’t want to be personal . . . that the teachings that K was giving would bring around a different group of people. Happy Valley land was to be used for that. And now it’s gone into other people’s hands . . . unfortunately. But schools here, if there are a great many schools here. What would happen? Can they maintain themselves? Private schools.

V—They come here for the very reason you and I come here. A beautiful, quiet, peaceful place . . . conducive to study.

K—I believe private schools are suffering a great deal. You see I used to talk practically every year at the other end (near Krotona Hill at the Oak Grove). Many people came here . . . gathered and had camps and all that. It’s all different since then. I’ve not been here practically since 1965. But I could come every year. Things have changed. Can’t serious people come here and maintain this atmosphere and this kind of beauty?

V—I think a lot of us are asking that question. I’m not so sure it’s good for the economy of the valley to have more houses, more people. The very reasons we all came here will have been destroyed.

K—How can we prevent the others from destroying it?

V—I think we’ll just have to say no. That the government will have to say no. That the valley should stay in orchards. In open space. I thought of one time writing to our congressman and proposing this as a national park . . . like Yosemite, like Yellowstone.

K—Will they allow it?

V—Well, the list of proposed national parks is long now. A very beautiful place north of San Francisco in Marin County is the newest national park . . . a strip of original seashore . . . in native grasses and sand. It has been preserved in the hands of one family ever since the Spaniards were there. This is the newest national park. Pt. Reyes National Park. We had our hand in proposing that. Now . . . in the Napa Valley . . . with its vineyards . . . they have made that into what we call a national monument which prevents any change to that valley. Not a park, but a national monument. Yet, it’s not as beautiful as this.

K—We have a school in England in Hampshire. There’s the start of a building there . . . the K Foundation owns it. You can’t build new houses . . . you can only improve or pull down old houses. You have to build on the same foundation. And you have to get permission to build from the planning committee—anything at all. We were going to build for 40 people. It took six months to get permission. It’s only an hour from London by train, but it’s a beautiful place and they said let’s not go and destroy it.

V—I think that’s what happened initially to our great national parks. Yosemite . . . John Muir in particular . . . said we’re not going to destroy this. This has to be kept. They brought United States officials there. And they agreed.

K—Can’t this be done here?

V—One of the problems — I was just thinking about this — it’s an exceptional day outside. If you live here long enough, you begin to think the whole world is like this. And it’s not. Locals don’t understand . . .

K—Can’t Ojai be maintained, sir. Through influence . . . through the machinery of government?

V—Let me say, I’m much more optimistic now, than I was last year for the Ojai Valley. Finally, the people who are in charge are getting the message from all of us down below, that we don’t want this to change, we don’t want more shopping centers and tract houses. We want to keep what’s left. What do you think that the citizens here can do?

K—Sir, do you know what is happening in the world? The citizens are responsible for destroying the world. Hmm? I used to go to India, except this winter. Every winter I spent 5-6 months . . . now it’s reduced to 3 months. You have no idea how it’s being destroyed. In Bombay, people are sleeping on pavements. Thousands of them. And under the tree they sleep. And the villages are being destroyed . . . 10 million of them. And the death rate is not so great as the birth rate. Citizens . . . human beings are responsible for this. Why can’t they stop it? Here in this valley . . . live all of you . . . for God’s sake you preserve this place. One place that’s not destroyed. Do you think there are serious people here? Serious in the sense . . . not all economically well established . . . but have roots in the valley . . . serious-minded people who say let’s maintain this atmosphere…this quietness, this beauty, this sense of . . . otherness. Do you know what I mean? Not at all the wrangles of the Catholic, Protestant, Communist, Socialist. Do you think there are such people here?

V—Yes, I think so. Many people of every political and religious affiliation feel exactly the way we do. Recently, a Committee to Preserve the Ojai was formed. They have four-five hundred members and they’re seeking to influence the kind of people who get elected. Working to defeat unneeded shopping centers. They’re working in a very practical way. And their numbers are growing. More people feel sympathy for them . . . and give them money. So, it’s happening here . . . but it has to happen fast. It can’t wait. There has to be a change in thinking. We all have to realize that open space out there is valuable. The most valuable thing we have. Of course, I write about this all the time to the people of Ojai. I don’t know how much attention they pay to it. Nothing much seems to happen. But I like you saying that.

K—You know, sir, in India, in Greece, and in other civilizations, when they found a beautiful spot like this they put a temple. Not a Christian temple or a Buddhist temple, but a temple. A thing that was beautiful and remained sacred because of the beauty of the place. I go to a school in south India. I spend three weeks talking to children. As you enter there, on a hill is a temple. And the feeling you have is of a sacred place . . . be quiet, be nice, be gentle, be pleasant to your neighbor, don’t kill, don’t hurt . . . all that atmosphere makes for beauty.

V—Do you think Americans are different from other people?

K—They’re much more energetic. They’re pleasure seekers. They’re fleetingly serious. I never have seen such race as this that want to . . . they can’t sit quietly. Go to the lakes, go off on guided hikes . . . oh . . . they can’t be by themselves. One year I was walking right up there on your mountains. I was standing looking at the beauty of the land . . . I could even see the ocean . . . A man came down on horseback . . . I was standing very still . . . He said, ‘what the hell are you standing so still for?’ . . . I said, ‘isn’t it a beautiful day?’ He looked at me and said, ‘oh, you’re the Christ child.’ (Much laughter here).

V— That was many years ago, wasn’t it?

K—Yes. I wonder, sir, you know Ojai. Can people treat this valley as a sacred place . . . not as a commercial center? A sacred place becomes beautiful . . . I hope you understand. People will come here because it’s quiet, restful, thoughtful, serious.

V—You don’t see any formal change . . . like, people coming here to form a religious center or a spiritual center. In the practical sense of the word.

K—I would . . . you see, sir, in India we have a place like this. A school . . . but people who come there are serious people. Treat it . . . I hate to use the word . . . as a sacred place. Unless you have this spot where people really can be thoughtful and serious you are going to destroy the world. You’ve heard of the river Ganges in India. We have a school on the banks of it, and it is very old. I found a statue by digging in the garden which is 6th century. Before that, I found something from B.C. So there’s a tremendous sense of atmosphere. I was talking the other day to Frank Waters and he was saying the American Indians felt the land was sacred and the sky was sacred. So keep it clean, keep it unpolluted. Here there isn’t that attitude . . . that feeling for the earth.

V—Yes, we’re supposed to conquer nature.

K—That’s it . . .

V—It says so in the Bible.

K—I know. In the East, there is a respect for the earth, respect for animals . . . not kill them. Here, you must always use it, build a factory, tear it to pieces. There’s that enormous vitality. Every time I used to come back to Ojai, before 1950, I say, “what a marvelous place!” But now I don’t come because it’s marvelous.

V—It would seem to me it would help much . . . if you would come here more often.

K—Oh yes. I’m coming . . . I didn’t come because the people I was working with didn’t want me to come here.

V—When you come, will you be staying here for a long time?

K—Oh, yes . . .

V—Well, this place will become what we think it should become. If we think positively about it, if we think this is the way the Ojai Valley should be, it will be that way.

K—That’s right. You know, Ojai Valley, is known all over the world. Because of the K Foundation. There’s a K foundation in England, in South America, and in India. People want to come here. That’s why that Happy Valley was bought. By Theosophist, by a group of people of whom I was the head. It was for that. Now it is . . .

V—It’s still there, the land, isn’t it?

K—But they’re different . . . and not interested.

V—I’m pleased to hear that you will be back.

K—Next year.

V—Do you plan to give up your place in Switzerland?

K—No, sir. There will be a gathering there. For about 3 weeks from all over Europe. And we’ll go on with that. And we’ll go on with Ojai, on with India. I used to go to Paris, Amsterdam, to various towns, but I’ll be glad to give this up.

V—Sounds like you’re more active than ever.

K—Let me tell you a true story, sir. In India, one time I was doing Yoga exercise and I see a shadow in the window. There is a big black wild monkey. I come quite close and it stretches out its hand. And I hold its hand. And its hand was rough and he wants to come inside. I said, ‘I don’t have time today . . . but come and see me sometime.’

V—Well, I understand you rarely grant interviews . . . on behalf of myself and the people of the Ojai Valley, I thank you for your time.

K: You are welcome, sir.

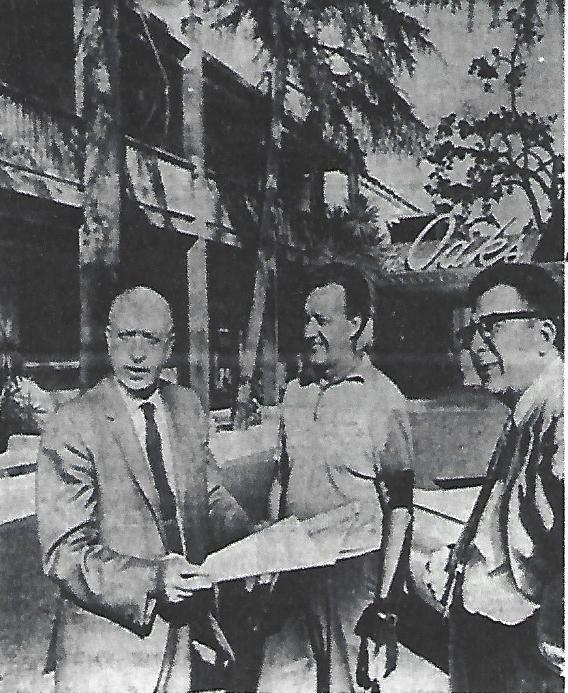

Oaks history — never dull

This article was contributed by longtime Ojai Valley resident Susan Roland. Roland recently discovered this article in the belongings she inherited from her mother. The “Ojai Valley Museum” has added the photos to the article.

Hollywood glamour

Oaks history — never dull

[Much of the following history of the Oaks hotel was taken from a series of articles for the Ojai Valley News by the late Helen Davenport, in 1962 society editor of the OVN.]

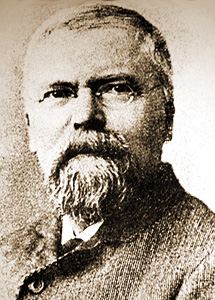

Staring as a quiet little country inn, the hotel opened around 1920 after many false starts and much talk. The ground was originally owned by P.K. Miller and he built a house on the site where he raised his family, according to Jennie Miller Griffin, his daughter.

The house burned down in the big fire of 1917.

A number of Ojai residents took an option on the property and became stockholders. These stockholders sold out at 50 cents on the dollar to Frank Barrington of Santa Barbara.

THE STORY GOES that the Barrington’s worked for a wealthy woman in Montecito, he as a butler and she as an upstairs maid. It is thought by others that she was a trained nurse. Both, it is true, were Irish and friendly. The wealthy woman ultimately died and left the couple $25,000 to run a hotel. Ojai was their destination.

Soon the hotel opened for business under the name of El Roblar.

Mr. Barrington in front of the El Roblar on March 4, 1929.

Following the death of Mr. Barrington, his wife continued to operate the hotel for many years. She brought many of her relatives over from the old country to visit and work in the establishment. Local residents held parties there, because the Ojai Valley Inn at this time was a private club.

Mrs. Barrington in front of the El Roblar in March 1929.

Mrs. Barrington was neat and orderly and well-liked. She saw to it that flowers were in the rooms and on the tables. As was the custom of the time in many homes, she had doilies and tidies strewn around for the homey touch. She took flowers to the Presbyterian church for many years.

Frank Barrington is remembered as a man of graceful charm. The New Years’ Eve parties are well remembered when he served his famous eggnogs to carollers returning to the hotel at midnight — a touch of alcohol in them for adults, unspiked for the youngsters.

Chauffeur-driven cars drove around the orange trees to the front door, letting out passengers who returned many times to the year-round hotel.

FROM A QUIET little country inn — the Oaks hotel became an internationally known hostelry. Changes in ownership followed in rapid succession, some tragic, some happy.

Mrs. Barrington sold the hotel to Canfield Enterprises of Santa Barbara. Mr. and Mrs. Canfield took over with many plans for changes and expansion. But these were put to a tragic end with the unhappy suicide of Mr. Canfield.

This was followed by the ownership of the Oaks going to the Cromwells of San Francisco and once more the doors were open with eager anticipation of a great future. Plans had been completed for the Matilija dam and hopes were high for an expanded hotel to take care of the expected influx of engineers, visitors and fishermen. Once again these dreams were shattered by the suicide of Mr. Cromwell.

Mrs. Barrington again took over the hotel. She soon leased it to Richard Paige (presently living on McAndrew road). This time some of the dreams became a reality. Paige and Morgan Baker, his associate, built the first bar in the hotel. A small intimate room it soon became a sought-after meeting place for cocktails and after-party and theater gatherings. It was noted for its “rump rail” an innovation which allowed the weary drinker to slouch in an orderly fashion with elbows and derriere well supported.

During the management of Paige and Baker, the present swimming pool was added to the Oaks attractions. Swim parties were frequent and the hotel became better-known than ever. The unhappiness of the previous years was completely forgotten behind the happy shouts from the bar and pool.

MANY STILL SPEAK of Martinez the bartender, who is said to have mixed a martini so memorable that people spoke of them in hushed and awed voices. They were, it is said, refused to those who were not regarded as worthy of such a mixture by the noble Martinez.

The management of Paige and Baker, as all things must, came to an end as these gentlemen became occupied elsewhere, and the Oaks — still owned by the Barrington estate — again sought ownership and management.

In 1952 the hotel was bought by Frank Keenan and the hotel entered into an era of splendor and activity it had not known before. Keenan was a former county assessor for Cook County, Ill., which is largely taken up by the city of Chicago, and he had glamorous plans for the hotel which he promptly began to carry out.

The present cottages around the pool were built and were soon filled with some of the most glamorous names of Hollywood and New York and less desirable places. Gangster Bugsy Siegal was a visitor. The dining room was remodeled and the bar enlarged. Keenan brought his genial brother Jim to act as host.

Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel

THE DINING ROOM was named the Chicago room and was greatly sought-after as a meeting place for important groups and glittering with social affairs. The opening with Bud Abbott as M.C. was rumored to cost $10,000. Guests arrived from all over the country and local residents who were lucky enough to be included talked endlessly about the gala affair.

It was during the Keenan ownership that the Oaks took on its present shape and form (that was 1962). The Keenan brothers wide acquaintance brought distinguished guests — and some who had glamour. Nevertheless, it was noted for its quiet dignity, fine cuisine and genuine hospitality.

It was said that Keenan wanted to make the Oaks into a casino a la Las Vegas. City officials who requested their names be withheld remember being approached with propositions and requests for “protection”. These officials let it be known that no gambling would be allowed in Ojai and this particular project was dropped.

The future of the Oaks was suddenly thrown into doubt when after four years of gaiety the Keenan brothers were indicted for income tax evasion back in Illinois. They were convicted and sent to prison.

The genial Jim Keenan died in prison; Frank Keenan completed his term and many hoped he would again resume ownership of the Oaks.

ONCE AGAIN the hotel closed and the halls were hushed. They remained quiet for over a year.

Through Keenan’s attorney, the hotel came into the hands of Heiress Lolita Armour (of Chicago packing house fame) and her new young husband Charles Madrin. It was thought that the hotel was being used as a tax write-off. A deal was made to trade the Armour estate in Lake Forest, Ill. for the Oaks hotel and once again the closed sign was removed.

On Jan. 1, 1958, a new regime started — one of toil and trouble — and a series of managers followed. There were seven in a two-year period before closing early in 1962.

Civic organizations held meetings at the hotel, lunches and dinners set by local residents, dinner dances were held, and the Wednesday style show around the pool were attractions. One manager installed electric heat lamps to be used on the terrace when the sun failed. A key-holders club was formed to make residents use the pool and bar and Richard Blalock’s orchestra played in the large dining room. Honeymooners loved the quiet of the mid-week and Hollywood celebrities dropped in for a rest in the country. Conventions were booked, but accommodations were such that only small crowds could be handled. The hotel was also the hub of the town. Genial Gino Giamari held sway as head bartender.

On the debit side, the various managers made many mistakes. One called an employees meeting once each month, however it was soon seen that those who got up to talk were soon fired. Another imbibed too much, another hated music and called the bartender when the lounge was filled with local people listening to a $ 150-a-week pianist. The bartender was sent home and the patrons left.

The thing the employees hated most was the Las Vegas mirror installed above the bar. Some thought this was not only to check on the bartender but on the low-cut gowns of the ladies. Along with the mirror a complete intercom system was put in, one that could be reversed so that employees’ every whispered word could be checked.

IN FEBRUARY OF 1962 the American Association of Retired Persons (Grey Gables) took a 90-day option on the Oaks, planning to sell units to its members. The price was around $500,000. However, the deal never closed because of the high expense of fireproofing and bringing the aging structure up to the building codes.

The Oaks remained closed for a while in 1962-63 until it was taken over by a well-remembered Ojai valley figure — Santa Barbaran Vernon Johnson. A big, bluff, bearded extrovert, who worked as a telephone company lineman-foreman and still does. Johnson had come into an inheritance and “had always wanted to run a hotel”. Several years prior to this, he had gained a measure of fame when he toured ’round the world (including through Siberia) in a converted Greyhound bus with his wife and 9 children. He bought the mortgage from Lolita Armour for $295,000 — making a $50,000 cash payment.

JOHNSON PLAYED a genial host at these parties, circulating from table to table with stories and goodwill. “He” became, in essence, the Oaks hotel and his face appeared on the menus, on the paper napkins, matchbook covers and even the tiny bar soap wrappers.

Localites were impressed with Johnson who went to Los Angeles one day and bought a $3,000 rare Macaw bird and installed it in the lounge.

Johnson lasted a year before filing for bankruptcy. Henry Coulson, a federal bankruptcy referee living in Ventura, then had the unhappy task of keeping the Oaks open and alive, which he did without the benefit of hotel experience until the Oaks was bought by a local group, headed by Rodney Walker and Jerald Peterson, at an auction in Nov. of 1966 for $230,000.

PARKING METERS FOR OJAI . . . ?

The following article first appeared on the front page of the Friday, January 12, 1951 edition of “THE OJAI.” That newspaper is now the “Ojai Valley News.” The article appears here with their permission. The author is unknown.

PARKING METERS FOR OJAI . . . ?

Some of our city fathers let drop a broad hint after their meeting Monday night that they would like to make a present of some parking meters to the city. This is rather a contrast to the propaganda put forward by council members some months ago to the effect that the issue of parking meters was not a serious one, but was introduced more or less to take people’s attention away from the proposal of a city sales tax, since passed.

They have not come out flatly in favor of the meters, but they have repeatedly brought the idea forward as a solution to what they term “Ojai’s parking problem.”

What parking problem? How can a town which has the greater percentage of its merchants concentrated in one block on one side of the street possibly have a parking problem? If the definition is such that the problem consists in not being able to park exactly in front of the establishment in which the driver wishes to shop, then, there is a parking problem. However, there is a large parking lot east of the city hall, and with the exception of a few unusual occasions, there has always been ample room to accommodate a large amount of cars, and without any overtime parking penalties. If shoppers still insist on parking on Ojai avenue, they are always able to find spaces within at least two blocks of the Arcade, which should not constitute a great burden, since many of these same shoppers are willing to beat their way down to Ventura or Santa Barbara and walk many blocks to do their shopping.

Nuts to the parking problem! If the city dads feel that our present rate of growth will demand more parking space in the future, let them make provisions for off-street parking while there is vacant land in the downtown area.

There is the parking lot adjacent to the city hall, already mentioned. There is land behind the Arcade, between Ojai avenue and Matilija street. There are various locations in the downtown section still unoccupied that will serve for parking if the council members fee that space is needed.

As to the financial picture, the meter company estimates that in Ojai, meters will bring in $4 per meter per month. With 110 meters installed, this would amount to approximately $5280 yearly revenue. Of this, the meter company takes half until the meters are paid for, which would take roughly two and one-half years. In the meantime the city would in all probability have to take on an extra employee to service the meters and make collections, since it has been the understanding, under the present city set-up that our city officials and employees are being worked up to and beyond their capacity. The additional employee would reduce the revenue from the meters, since it is a strange practice of people nowadays not to work for nothing.

It looks as though we are getting a little too large for our Levis. A city sales tax—yes. Off-street parking—perhaps, but KEEP PARKING METERS OUT OF OJAI.

Our problem: growth

The following article was first seen in the Thursday, May 24, 1962 edition of the “OJAI VALLEY NEWS” on the “OPINION PAGE” (Page A-2). It is reprinted here with their permission. It was an “EDITORIAL”, and the author is unknown.

Our problem: growth

A recent population analysis issued by the Ventura county planning staff revealed that the “Ojai planning area,” comprising Ojai, Meiners Oaks and Oak View, was growing slightly faster in the period April 1, 1961 – April 1, 1962, than the county average and about twice the rate of growth of the State of California.

Figures showed the county rate of growth as just over seven percent. This compares with an average of six percent the previous year. This is in line with recently-released statistics which told that Ventura had become the second-fastest growing county in the Los Angeles complex, second only to Orange. Its jump of over one percent in a year presages an increase year by year.

In the Ojai planning area the trend was slightly higher than the county average. We inched upwards to an eight-plus population increase this year. With plenty of land and water available, no slackening in this trend is in sight. No impenetrable barricades will be stretched across Highway 399 on the Arnaz grad or across other access, the Upper Ojai. Employees of the industries moving into the Tri-Cities, Oxnard, Thousand Oaks area will drive here some Sunday afternoon, fall in love with the valley and buy a home. Father will join the roughly 50 percent of the present commuters who live here and work elsewhere.

Another pertinent statistic came to light in the county survey. The highest rate of growth in the county was in the Simi planning area — a remarkable 27 percent increase. Second was Camarillo with 15 percent. Ojai was third at eight-plus.

A look at a county map at this point is revealing. Growth, which has been coming in the past from commuters who work in the Ventura area, will soon make a pincer movement into the valley via the Upper Ojai. Planners count on the development of the large ranches of the Casitas lake perimeter, but the Upper Ojai and even East Ojai’s proximity to the 27 percent increase of the planning area is even more startling. This is where growth is spilling over from the San Fernando valley coming this way along a Santa Susana-Simi-Moorpark — Santa Paula line.

Incidentally, great efforts are being made in Santa Paula to obtain industries. And, down the road a few miles in the Tri-Cities of El Rio, Montalvo and Saticoy, vast acreages are zoned industrial. Recently a 133 acre piece was sold to heavy industry.

Far from Ojai? Not really. From the Tri-Cities it is just as close to Ojai via Santa Paula as it is through Ventura. The same goes for Fillmore, which is due for San Fernando growth.

So here is our problem: proximity to growth. And, to a certain extent the cause of our present problems, for the valley has been growing steadily for a number of years. But the rate is accelerating — probably never to runaway proportions — but nevertheless as consistent as the rising sun. The population should inexorably double in ten years.

So, the future is already upon us. What to do about it?

The obvious answer: plan. The not-so-obvious answer: make decisions.

And, we mean make decisions now. Every decision deferred now means time that cannot be retrieved . . . . more pressure on the day when action is overdue, when action will be forced under pressure, perhaps under controversy, and always under haste, and extra expense.

Honestly now, wouldn’t our valley be a better place to live — a better planned community, if governmental bodies had been ready for growth, such as subdivisions, then years ago.

Only fast, massive, intelligent action on Ojai’s master plan, and by the county on the unincorporated sections of the valley (which are exceptionally vulnerable) can save the valley from a fate it does not want — or deserve.

OJAI SHOPS SHOW NEW FALL STYLES AT FASHION SHOW

The following article first appeared in “THE OJAI” newspaper on THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27, 1955. “THE OJAI” is now the “Ojai Valley News”. The article is reprinted here with their permission. The author is unknown.

OJAI SHOPS SHOW NEW FALL STYLES AT FASHION SHOW

A “Sunday in the park” atmosphere combined with perfect weather and the attractive surroundings of Orchidtown to make the Junior Women’s Club fashion show a delightful occasion Sunday afternoon

A concert by the Ojai Valley Civic Orchestra with Alan Rains conducting was the first attraction on the program, playing a medley of musical comedy favorites.

Commentator for the fashion show was Mrs. Peg Wells of Hickey Brothers, who introduced the models and described their ensembles as the latest styles were paraded beside the Orchidtown swimming pool.

Clothes for all occasions — sports, shopping, evening and even night wear — from the Little Acorn, Hickey Brothers, Fitzgerald’s, and the soon-to-be opened Campus Shop — proved that the woman shopping for her wardrobe in Ojai can be very well turned out indeed.

The large audience applauded the models, as well as their frocks, as they demonstrated professional grace and charm, from the youngsters who modeled sub-teen outfits, to the Junior Women’s Club members, to Mrs. Elizabeth Taylor, who wore the latest designs in half-sizes.

Outstanding trend was the hip-length, boxy jacket, with definite lack of emphasis on the normal waistline in suit jackets. Heather tones and purple were much in evidence, as were iridescent fabrics. Short dance dresses were excitingly designed; from handwoven ones to a dramatic white fitted gown with net ruffle coming into being just at the knee line.

Men’s fashions, too, came in for their share of attention, with dark-on-dark tones causing a good deal of interest.

At the conclusion of the fashion show, refreshments were served at tables on the lawn.

— The Ojai Staff Photo

“Nordhoff vs. Ojai”

This article first appeared in the Ojai Valley News in the October 22, 1969 edition. It is reprinted here with their permission. The author is Ed Wenig.

“Nordhoff vs. Ojai”

by

Ed Wenig

Legend has that Mrs. A.W. Blumberg, wife of the builder of the first hotel in the Ojai Valley in 1874, insisted on naming the proposed new town “NORDHOFF” because she said, Charles Nordhoff had called attention to the valley. Husband A.W. Blumberg and promoter R.G. Surdam graciously went along with the suggestion.

Nordhoff did write much about California in a book titled “CALIFORNIA For Health, Pleasure and Residence”, but Ojai Valley was not mentioned. He also wrote for newspapers and magazines and, it is said wrote about the valley. The claim is controversial and has not been substantiated, in the view of historians of recent times.

In April 1894, Charles Nordhoff did register at the Gally Cottages, and a few days later lectured at the Congregational Church in Nordhoff on “OLD TIMES IN CALIFORNIA.” The local newspaper reported in two columns everything Nordhoff remembered, but he apparently said nothing about visiting the valley before the town was named for him.

In 1894, the people of Ojai Valley were really stirred up about the name “Nordhoff,” for the only town in the valley. The editor of “The Ojai” suggested in an editorial that the matter had been fully discussed, and that every man, woman, and child in the two valleys, resident or visitor, should be polled. The result of such an election would determine whether the question should be forever dropped, or the proper steps be taken to have the name changed.

Feelings run high

Letters literally poured into the editor of “The Ojai” for and against changing the name of the town. Feelings ran high. In a later editorial the editor gave a mild admonition that letters on the subject should be “cleanly worded communications intended for the common good.”

Those who favored changing the name NORDHOFF to OJAI argued that postal clerks throughout the nation were mistaking Nordhoff for Norwalk; that people outside of the valley were confused as to what the post office address really was; that Ojai Valley was losing the effect of much advertising by having another name associated with Ojai; that the name Ojai was unique, the only name of its kind in the whole wide world! One petition was even circulated in east Ojai Valley for the establishment of a new town in the valley to be called “Ojai”.

Those who opposed the name change explained the “Nordhoff” was the name chosen by the people who founded the town 20 years before in honor of Charles Nordhoff, New York writer and traveler, who, they said, had mentioned the Ojai Valley in a newspaper article; that “Nordhoff” had too long been attached to the location to cast it aside unceremoniously.

Twenty-three years later, without much fanfare, “The Ojai”, on March 31, 1917, carried this notice under the Headline: “Now it’s Ojai”: “This telegram from Washington is self-explanatory. H.R. MORSE, FOOTHILLS HOTEL, YOU MAY ANNOUNCE CHANGE OF NAME FROM NORDHOFF TO OJAI. BEST WISHES. (SIGNED) JAMES D. PHELAN, U. S. SENATOR.”

Footnote: Those who have read “Mutiny on the Bounty” will be interested to know that its co-author, Charles Bernard Nordhoff, who was a student at Thacher School in 1898-1899, was the grandson of the Charles Nordhoff for whom the town was named.

THE ROAD FROM VENTURA TO OJAI

The following article first appeared in the Thursday, Sept. 4, 1958 (VOL. 1, NO. 34) issue of THE SENTINEL on the front page. THE SENTINEL was purchased by the Ojai Valley News. It is reprinted here with the permission of the Ojai Valley News. The author is Percy G. Watkins.

HISTORY OF THE VALLEY

Chapter Two: THE VALLEY IN 1900

(Ed. Note: This is another in a series of articles about the valley. Mr. Watkins has been a resident of the Oak View area since 1901. THE SENTINEL is highly honored to print this exclusive series.)

by Percy G. Watkins

THE ROAD FROM VENTURA TO OJAI

From Rocky Flats (Casitas Springs) north, the Ojai road followed the course of 399 to where it starts to run parallel to the railroad now. Then it crossed the tracks to stay close to it on the west ford of the San Antonio Creek. About where 399 leaves the railroad on to go up the San Antonio Creek Valley. The old road then continued about parallel with the railroad on up the Ventura River Valley.

A short distance from the ford, it crossed a private road going from the Hollingsworth Ranch House passing by La Crosse Station (near Casitas Springs) to fording the San Antonio Creek. It reached dry ground near where drying equipment was used in the processing of apricots. The apricot orchard was then south of the Hollingsworth home.

A man named Meyers (I do not know if he spelled his name that way), rented the ranch form Jack Hollingsworth, father of James Hollingsworth who lives there now. The apricot orchard was later very nearly taken away by floods.

The private road went on over the hill as does the Sulphur Mountain road now. On the left further on, where the road starts up the grade over Sulphur Mountain, was a small house with pens and some farm buildings.

Here William (Bill) Foreman lived with his wife and small children. He had horses and wagons and hauled for others—-hay, wood, etc. The place was known as “The Sheep Camp”.

This private road was also used by a Mr. Jennings, who lived where the Rocky Mountain Drilling Co. has its yards. He owned the land from there to Ranch No. 1 (now the Willet Ranch) in the Arnaz area. Here lie the remains of oil well equipment at the first summit of Sulphur Mountain road. However, the road at that time went up the canyon instead of over the present grade.

About a half mile or less up the canyon, in 1900, a crew was drilling a well with cable tools. The man in charge of this venture was a man named Van Epps, who in later years became well know in oil well drilling circles. He was killed several years ago in an oil well explosion near Fillmore. The well, of course, did not produce.

Next Week: A continuation of the road to Nordhoff (Ojai) as it proceeded past the home of Tom Bard (later U. S. Senator) and the first oil well drilled in Calif.

Evelyn Nordhoff is Returned

This article first appeared in the Ojai Valley News on February 19, 1999. It is used here with their permission.

Evelyn Nordhoff is Returned

By

David Mason

“The People of The Ojai can best show their appreciation of the generosity of the donors by keeping the fountain free from defacements, and by gradually developing around it village improvements of other kinds.” –The Ojai, Saturday, October 15, 1904

The journey to the town of Nordhoff, now Ojai, was long and tiring.

The dusty road was hardly passable in many places and the fact that the buggies had to ford rivers at least a dozen times didn’t help. The wild berries hanging down from the low tree limbs seemed to cover the trail.

There was a sign of relief when the buggies made it to the small camping area, now Camp Comfort, to take a rest. The stream was always running with cool water and the towering trees provided a shady nook.

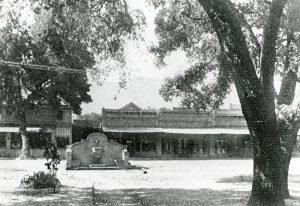

When travelers finally reached the small western town of Nordhoff, the first stop was the conveniently placed watering trough and drinking fountain in the center of town.

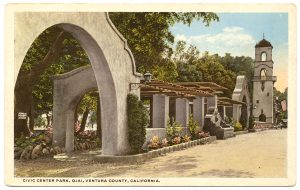

The fountain was a beautiful addition to the small community which had earlier lacked any architectural charm – it’s design would eventually become known as “Mission Revival” and it was one of the earliest examples.

The Ventura Free Press called it “one of the finest fountains in the state,” and described it in detail.

“On the side facing the middle of main street, we see the drinking place for horses, consisting of a stone trough about twelve feet long, two feet deep and two feet wide, always full of running water supplied from a pipe running out of the lion’s mouth.

“A division, the centerpiece of the fountain, runs lengthwise directly back of the horse trough, and is made prettier by having the stone cut into mouldings at either end. This piece is about fourteen feet long and fully eight feet high in the middle, and is rounding at the top. At each end of this, only a few inches above the ground, the poor thirsty dogs find drinking places.

“The drinking place for humanity is found on the side next to the Ojai Inn, and consists of a large bowl hollowed out of a piece of stone, into which runs a tiny stream of water from a small lion’s mouth.

“The donor has not forgotten the tired traveler, but has built a broad resting place for him on a big slab of stone. The Ojai newspaper refers to as ‘an ornament we should be proud of.'”

The fountain, built in memory of Evelyn Hunter Nordhoff in 1904, was indeed an improvement to the downtown block. The community of Nordhoff, the principal settlement in the Ojai Valley, had been established in 1874 and was still in its early stages of development. Evelyn Nordhoff was the daughter of Charles Nordhoff, the well-known author for whom the town was named.

Evelyn Nordhoff’s early life was spent at the family home on the New Jersey palisades, in an area which would eventually become known as “Millionaire’s Row.”

As a young woman, Evelyn enrolled at Smith College, located in west-central Massachusetts and founded in 1871 for the education of women. Her schooling was cut short after one year, with the reason given that “she was needed at home.”

Evelyn learned to etch copper and gained notice by producing decorative, printed calendars. She also created artistically-worked leather pieces.

According to researcher Richard Hoye, “An opportunity opened for Evelyn to visit England when her brother Walter was posted there as a newspaper correspondent.”

In 1888, the first Arts and Crafts exhibition was staged in London, and a co-founder of the exhibition society, Thomas Cobden-Sanderson, presented four lectures on bookbinding. Evelyn’s attendance at these lectures piqued her interest in that line of work.

When she eventually returned to America, the Nordhoff family made a touring visit to California. The Ventura County newspaper reported that the Nordhoffs passed through the seaside town and went directly to the Ojai Valley.

Returning to New York City, Evelyn obtained work with a bindery to pursue her interest in the art of bookbinding. There she learned to sew pages and to mend old books. This was the first level of the craft. Evelyn would learn the business from many teachers before she became proficient in the skill of bookbinding.

Evelyn opened her own workroom in Greenwich Village across from the New York University. Her artistry in the work of bookbinding began to gain attention for the young Evelyn as a woman and an artist. She possessed the Nordhoff sense of independence, and the initiative in pursing against the odds.

Training in a craft from which women had previously been excluded reflects a high degree of personal determination and she was a good example of a confident and talented woman, the first woman in the United States to take up the vocation of artistic bookbinding.

Evelyn Nordhoff spent her summer months in California with her parents, who, by this time, made their home in Coronado. In late summer of 1889, when Evelyn would again have departed from Coronado after a summer’s visit, her parents did not realize that this would be their last parting with their daughter, for in November they received word she had died.

She had suffered an attack of appendicitis, was operated on, and failed to recover.

The Nordhoff fountain was given to the community of Nordhoff by sisters Olivia and Caroline Stokes in Evelyn’s memory. The Stokes sisters had inherited wealth from banking, real estate and other interests in the New York City area. They were lifetime companions, never married, especially devout and well-known philanthropists. Their gifts were numerous and worldwide.

The Stokes sisters visited the Ojai Valley in 1903, staying at the Hughes home on Thacher Road, and were probably influenced by Sherman Thacher, founder of a nearby boys’ school, to build the fountain as a lasting memorial to this talented young lady.

Richard Hoye suggests that, “There may also have been a temperance motive. The banning of liquor was strongly supported in the community and by the Stokes sisters. A drinking fountain closely located to a horse trough would remove an excuse that stage drivers and their passengers might have had to resort to alcohol to slacken their thirst after a dusty trip from Ventura to the mountain town.”

In 1917, when Edward D. Libbey, Ojai’s greatest benefactor, began his transformation of the small town, he had the fountain moved back four feet to widen the roadway.

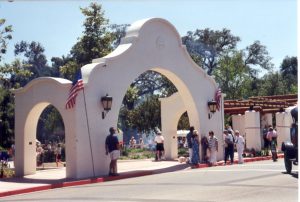

Libbey removed the Ojai Inn and built a beautiful, wisteria-covered, arched and walled pergola. With the fountain as the center focal point, an attractive entrance was created into the Civic Center Park, now Libbey Park.

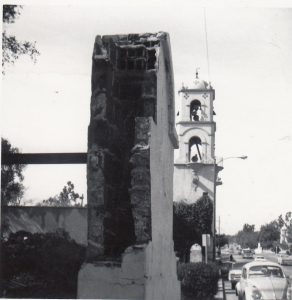

In the 1960s, the whole structure began to shown signs of age and suffered major damage from vandalism. In the turmoil of this period, the entrance arch was damaged by explosives and by 1971 the pergola and fountain were removed.

The bronze plaque on the fountain that was inscribed, “In memory of Evelyn Hunter Nordhoff, this fountain is given to the people of Nordhoff, 1904” was returned to members of the Nordhoff family.

With the restoration of this landmark – the pergola and the Nordhoff fountain – the bronze plaque has been returned to the people of the Ojai Valley. The plaque will once again be placed on this beautiful fountain which will be rebuilt in memory of Evelyn’s aspirations and accomplishments – a spirit which has prevailed in the history of the Ojai Valley, in its schools and its artistic culture.

Wini’s love prompted meat loaf generosity

This article first appeared in the March 15, 1989 edition of the Ojai Valley News. It is reprinted here with their permission.

Wini’s Love Prompted Meat Loaf Generosity

by

Bob Bryan

Walking down Main Street in Ventura, whom should I run into but Joe Mellein, of the justly famous Mellein family of Ojai.

Now when we Ojailoonlans get beyond the Casitas Pass we tend to get a little nervous, being so far from home. What better way to overcome homesickness than to share a malted milk with a long-time friend. I invited Joe to join me at the Busy Bee Café.

“I’m a milk shake man myself,” Joe said and I told him that was no problem.

The Busy Bee Café in Ventura (much like the Soda Bar and Grill in Ojai) is just the place for milk shakes and malts and nostalgia, all in equally generous portions. With its juke box and its songs of the ’50s (Johnny Mathis was singing “Johnny Angel” as we walked in), and its mini-skirted girls in red, the Busy Bee is just the place for anyone who wishes the ’50s had never stopped.

“How’s the family, Joe?” I ask. “Which ones?” Joe asks and informs me that at the last get-together in Sarzotti Park there were some 90 Mellein family members having at beans and tortillas and steaks and pies, all made in the old-fashioned way. There were about 30 Mellein kids in the 10-year-old bracket which made for a fine frenzy of baseball and volleyball.

Joe and I, perhaps because of the music (now they were playing Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Good”) began to talk about what it was like growing up in Ojai in the ’50s. Joe, one of 15 brothers and sisters, did the whole bit: altar boy, Boy Scout (Troop 504 with camping at Lion’s Camp and Rose Valley) and education at St. Thomas and later on at Bonaventure High.

Once, during those days of growing up in the ’50s, Joe and his father and mother (“She’s a beautiful lady and we all love her a lot”) planted a potted liquidamber tree in front of the family home at 506 Fulton St. Now it towers three stories high in all of its glory.

“Hey, remember the Topa Topa Café on Ojai Avenue?” one of us asks.

Who among us could possibly forget the Topa Topa Café, that renowned eatery, now an equally renowned bootery, or its meat loaf, served on Thursday, or was it Friday? Or Wini, that somewhat elderly waitress, who either loved your or did not love you. If Wini loved you, your portions of meat loaf were generous and promptly served; if she didn’t love you, you waited and stood a chance of getting a skimpy plate slung in your general direction.

We used to wait for our meat loaf plate at the Topa Topa like betters at the racetrack waiting for the results of a race to be posted. Except we knew that when the results came they were sure to be good: What a notable melange of succulent entrée, garden green string beans, and mashed potatoes swimming in homemade gravy. A vision of delight and a culinary masterpiece at $1.25 per plate.

Topa Topa was a hiring hall as well as an eatery. Many young men, in for breakfast, left with a day’s work as a tree trimmer or gardener before them. Philosophical discussions of the sort that still proliferate in Ojai abounded during these morning hours.

“What’s the meaning of it all?” someone might ask over coffee.

“Damned if I know” someone else might reply.

Back at the Busy Bee Café Joe and I decide, since our moo-cow blood content was still at manageable levels, to have at it once again. “Let me get this round,” Joe states and we split one of those giant vanilla shakes between the two of us.

“Got to go,” Joe says after the final gulp. “I’m having supper at my sister Andrea’s.”

“Is she a good cook?” I ask.

What a question! The Mellein women are not only good cooks, but in many cases, have become mothers of fine boys and girls who in turn become accomplished men and women. Owners of companies, therapists, future Air Force pilots, artists and writers of checks that don’t bounce are all part of the Mellien family. And, of course, pretty girls who know what kissing is about. “The jukebox is now playing Mel Carter’s immortal classic, “Kiss Me and When You Do I Know You’ll Miss Me.”)

“See you later, alligator,” one of us shouts to the other as we head on out the door down the street. Joe to a fine dinner of roast beef at his sister’s, and I back home to the Ojai Valley.