The Second Foothills Hotel by David Mason

“A greater Ojai shall arise sphinx-like from the ashes of homes and public buildings laid waste for the fire demon.” — The Ojai, June 29, 1917

The Foothills Hotel was to be no exception to the above quote. It would, indeed, rise again even more splendidly.

The Foothills Hotel was one of a number of hotels being built to accommodate the tourist business that was booming in the state of California, primarily in the southern half. The area had great potential as a place where people could go to escape the harsh eastern winters.

The Raymond Hotel in Pasadena (1886), Hotel del Coronado in San Diego (1887), Potter Hotel in Santa Barbara (1902) and the Foothills Hotel in Ojai (1903) were the legendary grand dames of the area. They were quickly becoming the talk of the western world.

Much of the grand hotels’ popularity was traced directly to the writings of Charles Nordhoff, a famous eastern author who had written glowing accounts of Southern California.

The population of the entire state of California in 1870 was 560,000, but by 1900 it had increased to 1,485,000; and during the same period, more than three million copies of Nordhoff’s books on California had been sold.

The Foothills Hotel had charm and elegance and was so in demand that potential guests would have to write in advance, send current financial statements and wait to be notified if reservations would be coming their way or not. Many waited, but few were chosen.

The hotel built cottages on the grounds for even more guests, and during its prosperous years that would still not accommodate the many requests for reservations.

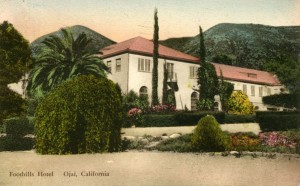

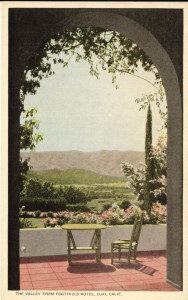

Built entirely of wood in a fire-danger area, the two-and-a-half story hotel made an impressive sight. High enough on the ridge to have a commanding view, across the manicured acres of the golf course, of the valley below, and with the majestic mountains as a backdrop, it was a place where travelers could gather to relax, play golf, or even ponder an investment in the young community.

The summer of 1917 was really not much different from most Ojai summers. It was hot, and the fire season had once again arrived, a time that most valley residents dread even to this day. And as luck would have it, a fire broke out in Matilija Canyon, because of carelessness by a camper, and quickly swept the hills and headed to the valley.

Many believed that Ojai was doomed, and the flight to safety began early in the evening. Of the 60 or more structures lost, the Foothills Hotel was one of them.

The fire was so consuming and the high winds were blowing so relentlessly that during the day feather mattresses were flying out of the windows of the hotel and helping the spread the fire to the valley below.

That fire, like so many before and since, ended with thoughts of the people being, “We must unite and begin to rebuild.”

E.D. Libbey, Ojai’s greatest benefactor, sent a telegram conveying his sympathy for the loss and said, “From such devastation and ruin will spring renewed energy and courage.”

Within days, the architects Mead and Requa, who had earlier designed the arcade and post office tower, were preparing plans for an even greater Foothills Hotel. The town newspaper proclaimed that there would be “no unnecessary delay in the building and furnishing of the handsome hostelry to be.

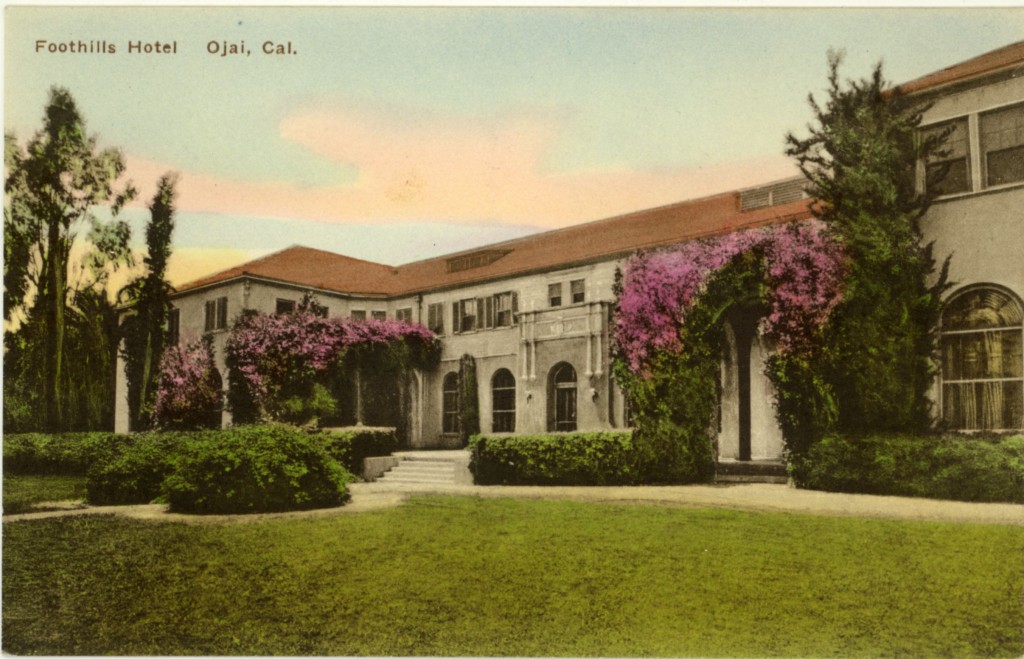

Built on the same foundation, the new hotel was a two-story, white stucco building, a model of completeness and easily surpassed anything of its size on the coast in modern appointments and equipment. A large and commodious lobby with a huge fireplace occupied the center of the lower floor of the main building. Large, easy armchairs, sofas and settees were invitingly arranged around the room.

To the left of the fireplace was the manager’s office, so situated that a clear observation could be had of all parts of the lower floor. To the back of this was a very cozy private breakfast or luncheon room, where special and private dinners could be served.

To the east of the lobby was the ladies parlor—large, roomy and comfortable, with a magnificent view of the valley below. Adjoining this was a parlor for maids and attendants across the hall, leading in from the east entrance, were the lavatories.

In the west wing of the lower floor was the large and spacious dining room, partitioned from the lobby with a glass panel arrangement, which could be folded back, converting these two rooms into a large ballroom.

To the north of the dining room was the kitchen, with its large range, modern steam dish-washing machine, and, with all the other modern appliances, it was one of the finest kitchens on the coast. Adjoining the main kitchen was the bakery and pastry kitchen.

To the east of the kitchen was a very inviting dining room for the help, maids and chauffeurs. The upper floor was given over entirely to 18 guest apartments with their individual baths.

Four cottages were located near the hotel that consisted of two and three bedrooms and baths, living rooms and sleeping porches. Just in front of the hotel were the tennis courts and golf course.

It was open only during the winter months, and because of the remoteness and lack of some services, many visitors simply wanted to make the hotel a temporary destination for resting from the rigors of life in the big cities, and for escaping from colder climates.

Much of Ojai’s social life centered around the hotel. Many delightful nights of entertainment were held and were open to the public in the spacious lobby. The most prominent was the first Frost-Coolidge Music Festival, which started in 1926. Many consider the event to be the inspiration for the present Ojai Music Festival.

The festival was announced to the valley through the local newspaper, The Ojai, in August of 1925 and was held in April of 1926. It was front-page news. “One of the greatest musical events that has ever taken place in America came to a close on Sunday evening with the final concert of the Ojai Musical Festival.”

It surpassed all expectations, great as they were; and the five concerts stood out as unquestionably the most wonderful thing that had ever happened in Ojai.

The Ojai newspaper continued to rave, “To have entertained at one time a group of world-famous musicians, any one of whom is able to command the attention of the music world, wherever he or she may be, to have heard during a period of three days three such famous aggregations as the London String Quartet, the San Francisco Quartet and the Little Symphony of New York under Georges Barrere, are experiences almost unknown in musical history.”

The lobby of the Foothills Hotel provided an auditorium so perfect that both audiences and artists confessed surprise. From the rearmost seat inside and the furthermost seat outdoors, every note was clear and distinct.

More than 500 people attended each concert, the greater number from the Ojai Valley itself, and about one-third coming from outside the valley.

One of the striking things about the festival was the arrangement of the programs. Only experts, such as Mrs. Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge and Mr. Franklin Jefferson Frost, could have planned five such complete and self-contained concerts.

Each was a gem; each brought out a special phase of music; each gave scope for a particular branch of instrumentality; and each gave the audience an opportunity to hear a different artist or group of artists. It was felt that the Ojai Music Festival would become a yearly event.

The hotel would continue to attract high society until the Depression of 1929, when the hotel’s popularity began to decline. It would continue to operate, but the years had taken their toll; and the Foothills Hotel was no longer the well-polished resort it had once been. The visits of eastern and Hollywood elite had all but ceased. Countless tales exist, some true, some legendary, and some nearly forgotten—of the notables who experienced the Foothills Hotel.

By 1942, the hotel was sold to the California Preparatory School, started in Pasadena as a military academy and then moved to Ojai. The hotel and cottages were remodeled for the use of the school, that would accommodate 100 students.

The property was sold again in 1955 for the establishment of Camp Ramah and enlarged to accommodate 200 students of the Jewish faith. Camp Ramah, needing more space, purchased El Rancho Rinconada and disposed of the beautiful Foothills Hotel.

The historic Foothills Hotel became but a memory in 1976 with the help of a demolition crew, and once more an Ojai treasure was gone.

By David Mason, Foothills hotel was a legendary grand dame of the area, Ojai Valley News, June 4, 1999