The Age of Reformation: Ethel Andrus and the Founding of AARP

by Craig Walker and Bret Bradigan

from The Ojai Quarterly

As Jack Fay remembers it, it was just a quiet business dinner with six people in a small meeting room at the Ojai Valley Inn. The air wasn’t charged with the momentous changes about to take place. Instead, they discussed legal incorporation issues and health insurance premiums.

As Jack Fay remembers it, it was just a quiet business dinner with six people in a small meeting room at the Ojai Valley Inn. The air wasn’t charged with the momentous changes about to take place. Instead, they discussed legal incorporation issues and health insurance premiums.

Dr. Ethel Percy Andrus organized the meeting. She represented the Grey Gables in Ojai on behalf of the National Retired Teachers Association, and Fay was her lawyer. The others at the meeting were Ruth Lana, Andrus’ long-time lieutenant; Dorothy Crippen, Andrus’ cousin; Leonard Fialco, the assistant to the sixth person present, Leonard Davis, an ambitious if yet only modestly successful insurance broker from Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

During that Ojai evening in 1958, the American Association of Retired Persons was born. And what it meant to grow old in this country changed dramatically. At first, the AARP was structured as a mechanism by which the National Retired Teachers Association, founded in 1947 by Andrus, could sell health insurance to the general public. The NRTA had been selling policies to retired teachers since 1956, and it had proven both profitable and popular. Insurance companies had turned Andrus down 40 times in the past 11 years. Yet in those pre-Medicare days she knew that people over 65 deserved the security and dignity that comes from knowing that they could rely on a doctor’s care.

When Andrus started the NRTA in 1947, 75 percent of people over the age of 65 lived with their relatives and 55 percent lived below the poverty line, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. In 1940, life expectancy was 60.8 years for men, 65.2 for females. In 2007, life expectancy figures were 75.4 and 80.4 respectively.

Some of the increase in lifespan can be attributed to medical advances, which the AARP has advocated and funded. Some could also be plausibly attributed to the dynamic lifestyle that Dr. Andrus pioneered and of which she was a living example: a lifestyle based on exercise, travel, lifetime learning, second careers, political and social activism, volunteering and community service.

Despite its modest origins in Ojai, the AARP now has 40 million members and is considered one of the most powerful nonprofit organizations in the United States. Its magazine has the largest circulation of any periodical. Its lobbying arm in Washington, D.C, is considered the most formidable. The organization extends into every area of aging, from leading-edge research to group travel discounts.

Fay, a former Ojai mayor and city councilman, is still practicing law. He is the sole survivor of that meeting since the death of Davis in 2001.

“As the meeting broke up, Davis took me by the shoulder and whispered to me, “You’ll never get anywhere in life if you don’t think big,” Fay recalls. “And I thought that was a heck of a good idea. So, I started thinking big. It didn’t work for me, but it did work for Davis.”

Leonard Davis convinced Continental Casualty to start up a pilot program for selling policies to everyone over the age of 65, not just retired teachers. It proved an immediate success. It went nationwide, with Davis as the sole broker. “He had the whole country as a fertile field to sell his health insurance,” Fay says. “So he made the best of it.”

Davis put up $50,000 in startup money. Dr. Andrus founded Modern Maturity magazine, now AARP Magazine, which lobbied for the interests of the elderly and, perhaps not coincidentally, served as an excellent marketing vehicle for the health insurance policies in those pre- Medicare years.

Within a year, the number of policies written went from 5,000 to 15,000. Within a few decades, Forbes magazine listed Davis as one of its 400 wealthiest Americans, with a personal fortune estimated at $230 million at the time he sold his Philadelphia-based Colonial Penn Group in 1984.

“I remember that evening vividly,” Fay says, “But I don’t think any one of us realized the import. Who could have predicted it?”

If anyone could have predicted it, it would likely have been Dr. Andrus, who founded the NRTA in 1947 before moving to Ojai from Glendale in 1954 to open a revolutionary new retirement home for teachers at Grey Gables.

A daughter of the progressive movement

She was born in San Francisco in 1884, the daughter of what she described as “a struggling young attorney” and “his proud and admiring helpmate.” She graduated with a bachelor’s degree from the University of Chicago in 1903 and began her long and storied teaching career at the Lewis Institute, the first junior college in the country, now the Illinois Institute of Technology.

She volunteered regularly at the nearby Hull House, founded by prominent reformer Jane Addams, who in 1930 became the first woman to win the Nobel Prize. At the time of Andrus’ volunteer service, however, the Hull House, founded just a few years earlier in 1897, was still an open experiment in social democracy, providing spiritual and educational uplift for its neighborhood of newly arrived immigrants in some of Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods. Each week, as many as 2,000 people came to the settlement house for night school classes, kindergarten classes, its famed public kitchen, its art gallery, gym, bookbindery, drama groups and library.

Dr. Andrus might be seen as a product of the Progressive Movement, which arose in the late 19th century as a socially responsible response to the abject poverty in which many of the new wave of immigrants lived, as well as against the greed of the Gilded Age of robber barons and growing economic inequality. Crusading journalists like Ida Tarbell and Frank Norris brought attention to the dangers and humiliations faced by factory workers and farmers. In 1906, during Dr. Andrus’ service at the Hull House, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, about Chicago’s meatpacking plants and stockyards, was published. With its nauseating descriptions of filthy practices and labor abuse, it led to such reforms as the Pure Food and Drug Act. The story of a Lithuanian immigrant and his family living in squalor and abuse, The Jungle intimately described many of the people for whom Addams, and Andrus, sought to provide a ladder out of poverty.

“I learned there to know life intimately and to value folks of different races and creeds,” Dr. Andrus wrote. “I saw there wonderful examples, not only of rehabilitation but of resurrection as well.”

Return to California

Her father’s failing health and eyesight brought her back to California. She took a teaching position at Santa Paula High School, which may have been her first exposure to Ojai, though she is said to have selected Ojai for her endeavors after giving a talk at Nordhoff High School in 1953.

In 1916, she was offered the assistant principal position at East Los Angeles High School. The following year, the principal retired and she was offered the job. At age 32, Ethel Percy Andrus had become the first female principal of a large, urban high school in the state of California.

With her flaming red hair and intense purpose, Andrus cut a memorable figure. One of her students, the actor Robert Preston of The Music Man fame, said, “The big iron scroll at Abraham Lincoln High School through which we passed said “Opportunity.” Isn’t it amazing that we didn’t know until we walked out: Opportunity had red hair!”

The lessons Ethel Percy Andrus learned at Hull House would serve her well over the next 28 years.

The school was notorious for its high rates of social dysfunction and juvenile delinquency. Despite the grand homes on the bluff overlooking the Los Angeles River, the district was also crowded with coldwater flats and tarpaper shacks from immigrant influxes: Chinese, Japanese, Italian and Mexican families particularly.

Lincoln Heights, considered the oldest neighborhood in Los Angeles, was always ethnically diverse, and racial clashes were common. It was the setting for the infamous Zoot Suit Riots, which began in 1942 because a Hispanic youth named Jose Diaz was allegedly murdered in Sleepy Lagoon in nearby Williams Ranch.

Asians, Latinos and Italians mixed with affluent founding families as well as Russian refugees from a Christian sect. Andrus wrote, “They lived in the flats near City Hall. They were an interesting people, led by an epileptic and financed by the elder Leo Tolstoi.”

Lincoln’s Legacy

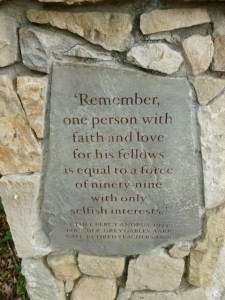

Dr. Andrus’ first task was to find some concepts to unify these immigrants and starchy patricians into a community. “Our faith became an obsession,” she wrote. “We must keep our many nationalities conscious and proud of their racial and national background, of the contributions made to the American dream, and to the insistent obligation they, the youngsters, must themselves accept in raising their own coming families with a double loyalty; respecting their own roots and the traditions alike of America and the land and faith of their forefathers.”

Every school day, at auditorium call, the students repeated these words: “I hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal. God hath made of one blood all races of men, and we are his children, brothers and sisters all.”

Her father’s hero was Abraham Lincoln. Her nephew was named Lincoln. Lincoln was also the hero of her mentor, Jane Addams, whose father was one of the founders of the Republican Party and a personal friend of the Great Emancipator. In 1919, Dr. Andrus was instrumental in having the neighborhood renamed from East Los Angeles to Lincoln Heights, and the 2,000-student school renamed Abraham Lincoln High School.

One of the anecdotes told about Lincoln was that after he gave a conciliatory speech about the Confederacy, a woman in the audience said, “But Mr. President, we must destroy our enemies!” Lincoln replied, “Yes, ma’am. But do I not destroy my enemies when I make them my friends?”

Dr. Andrus took that story to heart, always working to defuse tensions in the multiethnic community and build a shared sense of purpose. She forged strong connections. She worked with Los Angeles County Community Hospital to train nurses at the school. She encouraged civic associations like the Optimists to sponsor education awards and scholarships. Former athletes came back as coaches. Standout students went to college and came back as teachers. Besides Robert Preston, among her renowned alumni were actor Robert Young (who played Marcus Welby, M.D.) and Cardinal Robert Mahoney.

It didn’t take long before Dr. Andrus’ reforming zeal stirred up controversy, and delivered results. For example, she dropped Latin and Greek, and added vocational courses. “The discipline and faith routinely ingrained by the school reduced juvenile delinquency and brought a citation from the Superior Court,” wrote Scott Hart in “The Power of Years,” an Andrus biography commissioned by the NRTA and the AARP.

Among her proudest achievements was founding the Opportunity School with but one other certificated teacher, but with a staff of vital teachers: engineers, salesmen, preachers and the like. It later became the Lincoln Heights Adult Evening School,” she wrote. It served as a focal point for a community fractured along ethnic and economic lines.

Dr. Andrus said, “It was not a revolutionary idea–except in practice–to realize that the sons and daughters of folk pouring in from every corner of the globe had now some kind of common background, something to hold them together, a community pride.”

A lifelong learner, Dr. Andrus received her M.A. in 1928, and, in 1930, became one of the first women to receive her Ph.D. from the University of Southern California.

She also brought her faculty together into a tight-knit team. Ed Wenig, her drama teacher, moved to Ojai after his retirement to help her with the NRTA. Wenig became an esteemed local historian as well as a columnist for Modern Maturity magazine.

Wenig’s daughter, Patty Atkinson, was five in 1956 when the family moved to Ojai. “She was an imposing woman–she commanded a lot of authority,” Atkinson says of Andrus. Atkinson says her father adored Dr. Andrus, serving on many boards with her, including the NRTA, and helping with her many writing and publishing ventures after moving to Ojai.

Atkinson remembers her father, who had quite a peripatetic career including a stint teaching in the Philippines before joining forces with Dr. Andrus, talking about the day in 1942 that the Japanese students were rounded up to go to internment camps. “As the buses passed the school, the entire student body stood outside and waved,” she recalls. That measure of human respect was directly due to Andrus’ influence.

She also says her father would herd the students into assemblies and stage radio plays while the faculty held meetings. Often, Wenig would have to frisk students for weapons as they filed into the auditorium.

Even as Lincoln High School became nationally recognized for excellence, Dr. Andrus’ methods were studied and encouraged by the National Educational Association, her priorities changed to the very local near the end of the school year in 1944.

“My resignation came to Lincoln and myself as a sudden surprise,” she said. That morning the nurse attending my mother told me of her belief that my mother was to be a hopeless invalid. On the way to school, I determined that I could give to her the loving care she had given to my father during his blindness.”

Dr. Andrus was 60 years old, with a full life of significant achievements. But it was while caring for her mother that she became acutely aware of the problems faced by aging people. And so she launched the second, and most enduring, role of her career.

The Chicken Coop

In the AARP’s current television ads, the camera lens takes in a decrepit chicken coop, with the narration: “The unlikely birth place of a fundamental idea… Ethel couldn’t ignore the clear need for health and financial security, and it inspired her to found AARP.”

The chicken coop incident came not long after her retirement. While she was caring for her mother, Dr. Andrus kept busy with professional associations. She was named director of welfare for the Southern Section of the California Teachers Association, charged with seeing to the material needs of thousands of retirees.

It was a job she took personally, having learned that her pension, after 40 years in education, was $61.49 a month plus another $23.93 a month in an annuity, barely even a living wage. While she could rely on family money and other sources of income, she realized that very few teachers had such privileges waiting for them after their careers were over. Most retired teachers in those days were women, who were left especially destitute when widowed.

One day a local grocer asked Dr. Andrus if she would check on an old woman he hadn’t seen in several days. He gave Ethel the woman’s address. The people who lived there didn’t recognize the name, but then said, “Oh, you must mean the old woman living out back.” That’s when Andrus discovered that one of her retired teachers was living in a chicken coop. The woman was gravely ill, but had no money to visit a doctor. It was a moment that would charge Ethel Percy Andrus’ life with a new purpose.

She set about this new mission with great deliberation. The first step was to organize teachers nationwide in an effort to boost their collective clout. On Oct. 13, 1947, the 125 members of the California Retired Teachers Association present in Berkeley voted unanimously to form the National Retired Teachers Association.

That long journey eventually led to Ojai. Dr. Andrus began stumping the country, giving talks about the issues of aging, about the great gifts that elderly people could contribute to society, and about the means and mechanisms by which that pent-up potential would be realized. She brought an evangelical zeal to the task, repudiating the well-meaning social workers, retirement home activity directors, and even retirees themselves who fill the days of retired people with recreational activities like bingo or shuffleboard.

Older people need purpose in their life, meaningful and productive work, Dr. Andrus said. She objected to the term ‘senior citizen’ as isolating and demeaning. “We wouldn’t call 45-year-olds junior citizens,” she would say.

Friends and associates noticed a marked difference in Dr. Andrus. “She might talk with nostalgia of

the halls of ivy, and hours later with iron firmness about a business matter. Her ability to listen equaled her gift for quick brisk speech, everyone left her company feeling good about themselves,” according to The Power of Years.

Fay says that being in her presence “was an amazing feeling. She was an idealist and a visionary, and her lieutenants, Dorothy and Ruth, did the nuts and bolts work, and I did the legal work. She was a leader in the true sense of the word. She had great charisma, very articulate, although soft-spoken. She had such an aura about her, that I’ve been with her on several occasions when as soon as she walked into a room, silence came over it, and they looked at her in awe.”

One of the goals she set for the NRTA was to provide a model facility for active retirement. As she began casting about for a location, she might have remembered Ojai for its warm, dry air and bright sunshine from her days as a teacher in nearby Santa Paula; or she might have had conversations with local residents about the idea after giving a talk at Nordhoff High School, then located on El Paseo Drive.

Quiet Town, Big Changes

The morning after her Nordhoff talk in 1953, she saw two buildings for sale; a house on the corner of Montgomery Street and Grand Avenue, and a three-story building behind it. The property, Grey Gables, already had several small apartments, common living areas, a library and a large music hall. The NRTA put in an offer.

She had a grander vision of what retirement living could be than anything that had come before. Dr. Andrus foresaw a nursing home where the elderly might receive 24-hour care, and where they would actively work, volunteer and participate in the life of their community.

The city was skeptical. There were two other applicants for the site: Sam Sklar, who had recently bought Wheeler Hot Springs, and planned to operate the Gables in conjunction with his resort; and Alcoholics Anonymous, looking for a rest home for people in recovery. “The City was also not eager for us, grudgingly granting us the license which was essential to the sale only after being forced to decide between the claims of Alcohol[ics] Anonymous, a resort of uncertain moral standards and a retirement home. Finally, at long last, the City Council felt our institution was the least worst, and Grey Gables was in the forming,” Andrus wrote. Obstacles loomed, however.

The previous owners proved difficult. “The Sanfords were unpredictable; they wanted badly to sell, but

they hated the necessity of foregoing their dream,” Andrus wrote.

But the sale was a necessity. The Sanfords were about to be foreclosed on, owing $80,000 on the property. (Alee Sanford had her own, parallel vision for the property when she built it in the late 1940s, as a resident teachers’ club and library, with subsidized housing for local teachers.)

The first five years were a whirlwind of activity. Dr. Andrus brought Lana to Ojai as her trusted advisor, and they set to work “often substituting sheer energy for cash, and nervous energy for cash,” she later wrote. They created the menus, arranged the activities and attended the phones 24 hours a day.

The first resident, Emma McRedie Turner, from Chicago, arrived on July 17, 1954. “I was absolutely alone here, but the patrol car came by regularly,” she was quoted as saying in The Power of Years. Within 10 years, it had 85 residents.

“We of Grey Gables are certain that this project will be a pilot one, the first perhaps of many to prove to the world that retirement can be a dynamic adventure in gracious living,” Andrus wrote.

Jack Fay remembers his initial encounter with the red-haired dynamo. “In 1955, I first met Dr. Andrus at a City Council meeting, where I was representing an applicant for a land-use proposition, and she was there with her attorney, opposing my client, and it was a very contentious hearing, but not with her. I was just fine with her. I lost that case. She won it. Within a week, Andrus called me and said, ‘I wish you’d be my attorney.’ So I said, ‘Fine!'”

Little did I know what I was getting into. Dr. Andrus brought a large crew of people with her to Ojai from her former home in Glendale, including Ruth Lana, herself a former teacher. Ruth’s daughter, Lora, spent several years in Ojai, first as a student at Happy Valley School, then as an employee of the NRTA and AARP. “I remember opening these countless envelopes and shaking out the $2 [AARP membership fees] inside,” she said. The AARP grew from its first member in 1958 to about 400,000 in 1962, when the membership office was moved to Long Beach. The organization continued to be headquartered in Ojai until 1965, when the entire operation was moved first to Long Beach, then to Washington D.C.

Early residents of Grey Gables were attracted by Ethel’s vision of an active life of service, and so the Gables soon became an important asset to the community. Its residents served on local boards, tutored in the schools, taught classes at the Art Center and volunteered throughout the valley.

In 1959 the Ojai City Council, which had originally balked at the project, awarded Ethel Andrus and her Grey Gables residents a city proclamation honoring their many contributions to the community.

While she was busy lobbying politicians in Washington, D.C. (Lora Lana remembers her mother and Andrus living out of suitcases for weeks at a time), she also kept close touch with her people in Ojai. When a Nordhoff teacher, Herb Smith, and his wife were stricken with polio, Ethel spearheaded the fund-raising effort that paid for their house to be retrofitted for the wheelchair-bound couple.

Andrus cut quite a figure around town, says Anne Friend Thacher, who began working for both the NRTA and the AARP maintaining membership files. “No one called her Ethel. She had this striking red hair and was a very smart person.”

Dr. Andrus also brought her nephew, Lincoln Service, along with his young daughters, Barbara and Suzanne (Sandy) Andrus Service, to Ojai in 1954. The girls were seven and eight. Dr. Service served as the Gables’ medical staff. “We just loved Ojai,” Barbara says. “It was rural, and very beautiful, and very different from Glendale.” Even with Ojai’s laid-back country feel, Dr. Andrus insisted on proper decorum in dress and bearing. “One time she drove me down to Long Beach to go clothes shopping,” Sandy Service says. “We went into several stores where I would sit on the sofa and they brought out clothes for me to try. She would always pick these fancy silk suits. I said, ‘Nana, people in Ojai don’t dress like that.” She said, “A lady is a lady no matter where she lives.”

Thacher was a student at Happy Valley School at the time. Lora Lana was a year ahead of her. Thacher was promoted to secretary and continued to work for both organizations while a student at Berkeley. “They employed a lot of local people. The pay was pretty terrible,” she says. “One of my jobs was to correspond with people who had questions. One of the questions was, “How do you pronounce Ojai?”

Dr. Andrus was known for hiring young people. both to keep the former teachers in touch with youth, and also to allow the residents to use their wisdom and experience to guide young people. “Youth can and should be courted,” she wrote. “Youth will, in dividends of gratitude, pay high for the investment of the oldster’s time, interest and thoughtful attention.”

As the NRTA and AARP grew into national powerhouses, the local offices expanded. In 1954, the NRTA purchased Sycamore Lodge, a motel next to Grey Gables that fronted Grand Avenue; later, several apartments were added on the back and west side of the property. The Acacias nursing home was built in 1959.

Dr. Andrus set out the vision for the Acacias in an article for Modern Maturity in 1959, shortly after its purchase:

“The Acacias hopes to be more than a nursing facility, more than a convalescent home; it is a health center that will demonstrate the potency of helping older people discover the basis of their trouble and through care, friendly concern, and expert service find the right channels to recovery. The Acacias in its freshness and beauty of building and setting is in itself a strong factor in the attainment of this goal; its lines are restful; its colors refreshing; its furnishing modern and effective.”

Though she was instrumental in many causes of the day–working to end mandatory retirement and age-related discrimination, and to establish the now ubiquitous senior discounts–Dr. Andrus did so in an entirely non-adversarial manner. She didn’t lead marches, sit-ins, political campaigns, etc. It was all done through education, research, advocacy and programs by her own membership organizations.

Through the research arm of AARP, she exploded many commonly held myths, stereotypes and assumptions about aging. She used this new knowledge about aging to promote a new image of growing older and retirement … from the end of one’s creative life to the beginning, from isolation to involvement, from deterioration to continued growth, from a time to be feared to a time of opportunity and renewed productivity.

Leonard Davis and Dr. Andrus made a formidable team, lobbying tirelessly for the passage of Medicare in 1965.

Davis died at age 76 in 2001. Despite a few scrapes with regulators and Congressional investigative arms (he lost his lock on being the sole insurance broker for the AARP during the 1970s), he was a generous benefactor to many causes. In addition to the many millions he and his wife Sophie gave to universities, museums and cultural centers, he endowed the Andrus Gerontology Center at the University of Southern California, the first center in the country devoted to training medical staff to treat elderly patients.

Dr. Andrus died July 13, 1967, active to the end, mourned by many and replaced by none. Though she had unlocked the vast wealth held by retired people as they were brought out of isolation and into the mainstream of America, her personal fortune, according to Fay, was valued at less than $100,000.

She was eulogized by President Lyndon Johnson as well as by Ojai friends and neighbors. “In Ethel Percy Andrus,” he wrote, “humanity had a trusted and untiring friend. She has left us all poorer by her death. But by her enduring accomplishments, she has enriched not only us, but all succeeding generations of Americans.”

Ethel_Andrus_story in PDF.