Helen Baker Reynolds (Part V) by Ed Wenig

[This week we quote from the chapter School, in the book “Family Album” by Helen Baker Reynolds.]

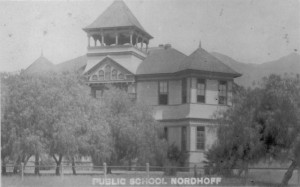

“The grammar school stood just across the road, opposite our side gate. It was a drab, square, two-story building, topped with a cupola housing the school bell, and with two out-houses behind it.

“The schoolyard of hard adobe soil was bare except for one large oak and some pepper tress next to the road, which the girls and the younger children congregated at recess and played tag or drop-the-handkerchief. There also in the spring we played marbles. The marble games were segregated according to sex, since the boys scorned competition with the girls, we being, of course, inferior.

“Playing for ‘keeps’ was forbidden; it was a form of gambling. The ‘bad’ boys sometimes broke the rules,at least, so we suspected. Their ‘smart-alec’ talk about the aggies changing hands was calculated to be not loud enough for a teacher to overhear but audible to the girls nearby, who presumably would be vastly impressed by the enormity of the sin.

“Baseball was the boys’ year-round sport. It was played in the bare yard on the other side of the school, participants daring to slide into base would return at the sound of the school bell, grimy with mud or with dust, according to the season. Because of this invariable result, sliding to base was forbidden. Those who were known to have broken the rule were kept in after school. The crime was not quite bad enough to merit the rawhide strap, but it gave a boy a high standing among his fellows. If often enough, he became an athletic hero.

“I hated school. The freedom of my earlier childhood made long confinement irksome, and the gentle propriety of our home had prepared me not at all for meeting the tough-and-tumble elements which, in our grammar school at that time set the predominant tone.

“On the walls of the outhouse words were scrawled which to me were unfamiliar but which I suspected, with good reason, were simply not nice at all, and some of the children often would giggle at things that made me blush.

“Most of the boys I considered dreadful. They were always yelling and pushing and starting fights in the schoolyard, whereupon Mr. Egerton, the principal, would haul them into the ante room where hung the rawhide strap.

“Mr. Egerton and his rawhide strap assumed in my mind an almost nightmarish quality. Actually he was a virtuous man and a conscientious principal. Toward me he was never harsh. I was even known as Egerton’s pet, being one of the minority who did the assigned homework and more often than not obeyed the rules. I knew at the time that I really ought not to harbor dislike of the principal, but the feeling of aversion persisted nevertheless. It may have been due to my inherent and home-instilled horror of violence, and Mr. Egerton, thanks to a host of obstreperous boys, seemed forever engaged in violence of the rawhide strap variety.

“Slight misdemeanors rated knuckle raps with the ruler; more serious offenses, the rawhide. He would collar the culprit and lead or drag him into the anteroom, from whence would issue horrifying sounds. Most of the boys in the schoolroom and even some of the girls would titter, a few of the boys of the bolder sort letting loose subdued guffaws, but the ‘nice’ girls would look distressed and would try their best not to listen.

“Friday afternoons after recess the whole school had an hour of singing in the assembly hall. Miss Reppy, who taught the primary grades (the one teacher whom the children loved) played the piano accompaniment, and Miss Shaw beat time for our singing, while Mr. Egerton stalked about, keeping order, ruler in hand.

[Editors Note: Mrs. Reynolds entered Nordhoff High School the year it was opened.]

“An excellent faculty had been procured, headed by Mr. Bristol, a competent, scholarly man. The community’s pride in its new school, and the spirit of the teachers, were reflected in the attitude of the 55 students, most of whom were entering high school with more or less serious purpose.

“I loved the school. With ambition and enthusiasm I proceeded to make straight A’s. Every month when I brought home a perfect report card, Father would smile his approval. I never knew at the time, however, what lay behind his invariable remark: “That’s just fine, Helen. That’s just fine. Mother, this little girl is doing all right. Yes, sir, the Ojai Valley is the Best Place in the World.”

The Intangible Spirit of the Ojai, by Ed Wenig