When Vickie Robertson, long-time employee of Ojai Village Pharmacy, discovered that she had been working in the oldest pharmacy in Ventura County, she became a historical sleuth. “Wow,” she said, “I wonder how many people know this,” and began her investigations.

Robertson traced a lineage of pharmacists in Ojai who have owned the business since 1891. As she searched through books, talked to historians, and waded through reels of microfiche at the Ojai Library, she discovered that the store’s line of pharmacists had been unbroken since Dr. Benjamin Levan Saegar first established the Ojai Drug Store in Nordhoff (Ojai’s original name).

In the first issue of The Ojai newspaper (partly owned by Dr. Saegar), dated October 27, 1891, the Ojai Drug Store advertised, “Constantly on hand – a full stock of fresh drugs, cinnamon from Ceylon, ginger from Borneo, perfumes, fancy chocolates and toilet articles, stationery, cigars, tobacco, etc. Physicians prescriptions a specialty and promptly attended to day and night.” The population of the town was 300 people.

As Dr. Saegar was the first person in town to have a telephone and a drug store with soda fountain, his store became a hub of the village. People came to make phone calls for a few pennies, meet their friends, have an ice cream float, and exchange news of the day.

According to historian David Mason, “The Ojai Drug Store also doubled as the newspaper office, and Dr. Saegar was the paper’s first editor. People could drop off articles, ads, and pay for subscriptions while filling their prescriptions.”

In 1911 Dr. Saegar sold the store to W.V. Skillman who owned it only briefly although he did find the time to refurbish the soda fountain. The following year Skillman sold it to S. D. Nill who owned the business until April 1916 when he sold it to entrepreneur and pharmacist John Flanagan.

The Ojai reported, “He (Flanagan) is a thorough business man, and knows the needs of the trade, and that he must be able to deliver the goods at the right prices, to hold the trade, as communities are loyal to home interests if the ‘home interests’ are loyal to the community. Drop around and get acquainted. Mr. Flanagan is a live wire and thrice welcome.” In early 1917 Flanagan expanded his business to a larger space at 202 Ojai Ave at the site of Thomas Clark’s old horse livery.

During this same period, Thomas S. Clark owned the property along Ojai Ave between Signal and Matilija streets to the boundaries of the present Rains Department Store. Clark was also the County Supervisor for Ventura from 1904 to 1936. In 1895 he opened a horse stable and livery on the corner of Ojai Ave and Signal St. In 1910, when automobiles became available, Clark expanded his livery business into an auto livery. He enlarged the building to110 Signal Street, part of his property behind the former horse livery. Clark had the first auto showrooms in the Ojai valley.

During this same period, Thomas S. Clark owned the property along Ojai Ave between Signal and Matilija streets to the boundaries of the present Rains Department Store. Clark was also the County Supervisor for Ventura from 1904 to 1936. In 1895 he opened a horse stable and livery on the corner of Ojai Ave and Signal St. In 1910, when automobiles became available, Clark expanded his livery business into an auto livery. He enlarged the building to110 Signal Street, part of his property behind the former horse livery. Clark had the first auto showrooms in the Ojai valley.

In 1917 Clark sold his auto livery to E.A. Runkle who consolidated the “auto, livery and stage coach” business to the Signal St location enabling Flanagan to move his pharmacy to the corner location on Ojai Ave the following year.

In 1917 while World War I raged in Europe, two major fires descended upon Ojai, one in June and one in September. The June blaze took five lives and destroyed 70 homes, a church and part of the high school. Tom Clark’s home on Matilija and Signal was saved by a bucket brigade. “The second fire (in September) was caused from a gasoline stove explosion in the lunch room of Miss Elvie Presley at 11 o’clock and spread quickly in all directions,” reported The Ojai.

This second fire destroyed much of the downtown area including all the buildings along Ojai Ave up to the present Tottenham Court. Although townspeople and merchants helped move the drug store’s medicines and bottles away from the flames, Flanagan’s loss was considerable. He had over $3 – 3.4K in damages from broken bottles, exploded packages, and melted candy’s, soaps, chocolates and perfumes. Until Ventura County took over the fire department in the late 1920’s, local volunteers and US. Forest Service rangers fought the fires. Ojai was provided with it’s first fire truck in 1918 thanks to the generosity of E. D. Libbey.

Due to the damage and loss all businesses experienced, “The Ojai” urged “all the people of the Ojai to buy their goods more generously than ever before, of our local dealers, who have suffered so seriously and not to permit reduction in prices for slight damage by water, fire or smoke.”

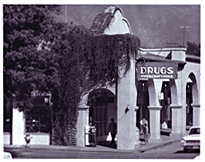

Town benefactor E. D. Libbey built the Arcade and Tom Clark replaced the wooden frame building with massive stones that form the Signal Street walls today. John Flanagan celebrated the opening of his new store on June 27, 1918 with music and dancing. “The residents of the Ojai enjoyed a royal good time,” the Ojai reported. “Ice Cream and sodas were served free to all who cared to indulge and there were plenty of good smokes for the smokers.”

In 1919 George and Ida Crampton took over the Ojai Drug Store from Flanagan. Flanagan left the pharmacy for the automobile business and started the new Dodge car agency in Ventura. After the purchase Crampton invited the town “to an open house to come to his store for a good time. The products of his soda fountain will be dispensed free during the evening,” The Ojai reported. The population of Ojai was 500 people.

In 1924, the Cramptons sold the pharmacy business to R. J. Boardman, who ran it as Boardman’s Drug Store until 1947 when he sold it to Dr. E. K. Roberts and pharmacist Tom E. Clark who named it The Village Drug. (Dr. Roberts was Tom Clark’s brother-in-law).

In 1924, the Cramptons sold the pharmacy business to R. J. Boardman, who ran it as Boardman’s Drug Store until 1947 when he sold it to Dr. E. K. Roberts and pharmacist Tom E. Clark who named it The Village Drug. (Dr. Roberts was Tom Clark’s brother-in-law).

Roberts and Clark owned the business until the early 1955 when they sold it to Mr. Ripley. However, within four years, Ripley sold it to pharmacist Alex Golbuff.

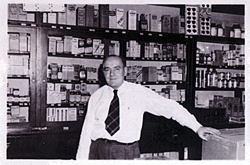

Golbuff ran the business from 9:00 AM to 9:00 PM six days a week and 9 AM to 5 PM on Sundays for twelve years. One day in 1968, as the legend goes, Leonard Badt walked into the pharmacy and said, “I would like to buy this business.” Golbuff, fed up with working so many hours for so many years, said, “Take it!” And Badt did just that.

When Badt purchased the pharmacy business, he also had his eye on owning the land and building as well. He then approached Tom S. Clark’s daughters and asked to buy the property. They promised to sell it to him.

Thomas S. Clark and his first wife Ella Bakeman had nine children. After she died at the age of 55 in 1924, he remarried. When Clark died in 1940, he had willed the buildings on the corner of Ojai Ave and Signal St to his second wife Ida Brambel Clark.

Ojai resident Tom Clark Conrad, whose mother Margaret was one of T.S. Clark’s daughters, said, “My mother and her three sisters bought the property from Ida Clark and then sold it to two other sisters Dortha Clark Roberts and Elizabeth Clark. When Roberts and Clark died, the estate honored the promise made earlier to Leonard Badt and sold him the property. Badt’s two sons still own the building.”

In 1967, Stan Lazarus purchased the “other” drug store, Ojai Pharmacy, then located at 328 E. Ojai Avenue and the current location of Bonnie Lu’s. He bought the business from the Carsner family. A very popular man about town, James E. “Jack” France managed the store. After the tragic death of Leonard Badt in 1982, Lazarus purchased the “Ojai Drug Store” business from Leonard Badt’s estate and merged the two stores renaming it Ojai Village Pharmacy. June Conrad, Tom’s wife, said, “My friend Doris de Groot Mayfield had her first date with her future husband at the soda fountain in that pharmacy in 1942.” This year Ojai Village Pharmacy celebrates 120 years of unbroken pharmacy business in Ojai.

Many thanks to those who made this story possible: David Mason, Patricia Frye, Tom and June Conrad, the Ojai Valley Library, the Ojai Valley Museum, and most of all – Stan Lazarus and Vickie Robertson. Mason said, “It’s a nice thing that she (Robertson) has done and worked it through so long. It’s good for the historic preservation aspect of the valley. The Ojai Museum should have a copy of her findings, and I would encourage her to do other projects.”