The following article first appeared in a newspaper on November 22, 1961 that, eventually, became the “Ojai Valley News”. It is reprinted here with the permission of the “Ojai Valley News”. The author is Ed Wenig. Wenig wrote a series titled “Intangible Spirit of The Ojai”, but failed to title each of his articles in the series. So the “Ojai Valley Museum” has added “(No. 1)” to the title.

Intangible Spirit of The Ojai (No. 1)

by

Ed Wenig

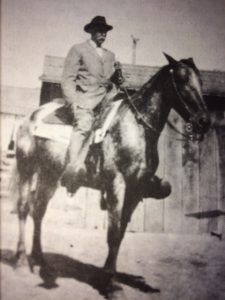

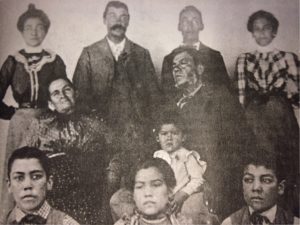

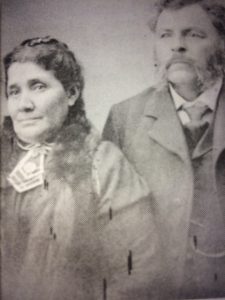

Little six year-old Rudolfo Reyes desperately clung behind his brother Pedro as they rode in a long pack train to their Cuyama home. The year was 1894. Don Rafael Reyes, his wife Maria and their 10 children, all on horseback with a long string of pack animals, were wending their way from Ventura to the Matilija Canyon, up the north fork to Cherry Creek, then over hill and dale to the adobe ranch home. This trail was the only way to reach their destination from Ventura. The present highway was not a reality until the early thirties.

On the large cattle ranch Rudolfo’s older brothers had the exciting job of herding and branding cattle in the spring and fall roundups. Of course, branding in those days consisted of the time-honored method of roping, throwing to the ground, tying, and applying the branding iron to the struggling beast — a far cry from the modern use of the narrowing corral and the chute with the animal locked in fore and aft. Vaqueros from neighboring ranches helped each other. Rudolfo had the original branding iron, in the shape of a wine glass, and also the original registration papers issued to his father, Don Rafael, in 1858.

All the hardships of the early California pioneers were part of the isolated Reyes Rancho, even into the early part of this century. With only a trail over the mountains to Ventura, and a rough and tortuous wagon road to Bakersfield, acquiring the necessities of life and the care of the sick were a problem. The round trip to Bakersfield by wagon to bring 40 sacks of flour took three or more days.

As in the case of most of the old early California ranches, the latch string was always out for strangers who often stayed overnight. Good and bad people were welcome, with no questions asked. Says Rudolfo: “Once a man working for my father turned out to be an outlaw who had killed several men. When he heard “the law” was after him, he climbed up into the attic of the old adobe. Here he waited as the officers came in. His guns were at “the ready” as they searched the ranch. The officers went away and the outlaw skipped out!”