The Little Brick Schoolhouse by Patty Fry

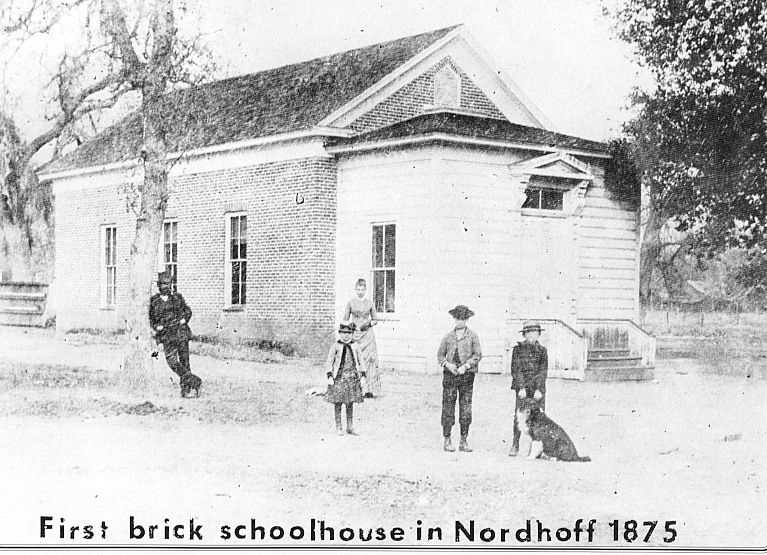

In 1874, Andy Van Curen circulated a petition for another school that would be closer to the newly established village. As soon as school superintendent F.S.S. Buckman approved it, Abram Blumberg started making the bricks for the structure near where the main tennis courts are today in Libbey Park. A note in a July, 1874 issue of the Ventura Signal, states, “A brick kiln will be burned on the Ojai during the summer.”

One night a mountain lion sauntered through the drying area behind Blumberg’s Nordhoff Hotel and left a paw print in a brick. Blumberg gave this keepsake to his daughter, Inez.

While the bricks were being made, the townspeople immediately erected a temporary schoolhouse on Matilija Stree west of John Montgomery’s house. Soule and Pirie offspring reported in later years that after having lessons in this crude structure for a few months, the students considered the new brick schoolhouse a “palace.”

The oblong brick schoolhouse consisted of one classroom and two anterooms. It had a sixteen-foot ceiling and four windows on each side allowed sunlight in. A drum in the center of the classroom provided necessary heat. The students sat in pairs at double desks and there was a bench in front of the teacher’s desk for reciting. Mrs. Joseph Steepleton, who had previously conducted a private school in her home, accepted the teaching position for the newly established Nordhoff School District.

The oblong brick schoolhouse consisted of one classroom and two anterooms. It had a sixteen-foot ceiling and four windows on each side allowed sunlight in. A drum in the center of the classroom provided necessary heat. The students sat in pairs at double desks and there was a bench in front of the teacher’s desk for reciting. Mrs. Joseph Steepleton, who had previously conducted a private school in her home, accepted the teaching position for the newly established Nordhoff School District.

The original wooden schoolhouse was moved to the top of the grade and became known as the Ojai School District. In about 1883, upper valley residents built a larger schoolhouse two miles east, reportedly on the boundary of Hobart’s and Robinson’s properties. This school operated independently until 1965.

Jerome Caldwell and F.S.S. Buckman were among those who taught at the little brick schoolhouse. Anna Seward taught there during 1884. She introduced calisthenics and music to the children. Agnes Howe was the teacher between 1885 and into the 1890s. Howe once claimed that the single room schoolhouse had more bats than children and she spearheaded an incentive program to rid the place of the bats.

In 1882, when enrollment reached sixty students, a brown bungalow was added to the brick schoolhouse.

Teachers were responsible for school maintenance. They asked the older students to sweep the floors and build fires for heat. Students carried water from nearby streams or cottages and everyone drank from a pail using a community dipper. The children liked to play stick ball, pum pum pull away and marbles for keeps. There was also great interest in baseball, riding and hiking in those days, recalled Miss Howe.

Clara Smith, a well known figure in county education, taught at the village school and served as its first principal until tragedy struck in 1892. Her fiance, Scottish-born Robert Fisher, a blacksmith by trade, died suddenly of typhoid fever on the day they were to be wed.

Clara, the daughter of community leader, Daniel Smith, first taught school in Nebraska at the age of 15. She was so devoted to education that she once walked from Nordhoff to Ventura to take a teacher’s exam. Her career progressed from teaching at most local schools, as well as some outside the county, to serving as County Director of Rural Education and Assistant Superintendent of Schools. Clara Smith retired from the school system in 1935.

Teachers weren’t in abundance during the early years, as was illustrated by an incident occurring in 1895. When Agnes Howe fell from a bicycle and sprained her ankle, the school closed for a week while she healed.

In 1889, 14-year-old Charlie Wolfe, son of Judge and Mrs. Irvin W. Wolfe, died at the school when he fell from a tree he was climbing. His twin sister had died at birth.

In 1893, Miss Beal’s primary grades had six more students than seats. It was obvious that the community had outgrown its little brick schoolhouse.

When parents initiated plans to build a bigger and better school, others reminisced about how well the brick building had served the community. Not only had it been the fountain of education for their children for twenty years, but also a church, a meeting place and a social hall.

Every new religious group used it as a place of worship while building its church. It was the very heart and soul of the village. Within those brick walls the townsfolk held their entertainment, made new friends and cemented relationships. That is where community leaders made their decisions, some of which affect our lives today.

But progress is progress and the fact was that the town had outgrown their school and a new one was built to accommodate the education of the valley children.

After the community abandoned the old schoolhouse, the brown bungalow was moved to 570 North Montgomery Street and Ezra Taylor, who ran a machine shop in town, moved his family into the brick building. It was home to the A.E. Freeman family around 1910. Mr. Freeman, a local grocer, reportedly added the second story and began the transformation that camouflaged the original brick outer walls. G.L. Chrisman bought the Freeman home in June of 1916 and the Alton Drowns lived there during the 1920s and 30s.

After the community abandoned the old schoolhouse, the brown bungalow was moved to 570 North Montgomery Street and Ezra Taylor, who ran a machine shop in town, moved his family into the brick building. It was home to the A.E. Freeman family around 1910. Mr. Freeman, a local grocer, reportedly added the second story and began the transformation that camouflaged the original brick outer walls. G.L. Chrisman bought the Freeman home in June of 1916 and the Alton Drowns lived there during the 1920s and 30s.

In 1946, Major Richard Cannon bought the former schoolhouse and opened the Cannon School there. One year later, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Cataldo converted the school into the Ojai Manor Hotel and began renting seven rooms. Although these owners had altered the little brick schoolhouse beyond recognition, until the 1980s, a keen eye could detect Blumberg’s misshapen, aged bricks as foundation beneath the time-honored facade at 210 Matilija Street. The old bricks are still visible on the inside kitchen wall.

In the 1980s, Mary Nelson removed the old Old Manor Hotel and opened it as a bed and breakfast. In 1999, the old schoolhouse, once again beautifully remodeled, has resumed as a bed and breakfast under the name, The Moon’s Nest Inn [now The Lavender Inn].

The above is excerpted from Patty Fry’s book The Ojai Valley: An Illustrated History. In 2017 the book was updated by Elise DePudyt and Craig Walker. It is available in the museum’s store and through Amazon.com.

The above is excerpted from Patty Fry’s book The Ojai Valley: An Illustrated History. In 2017 the book was updated by Elise DePudyt and Craig Walker. It is available in the museum’s store and through Amazon.com.