Wheeler Hot Springs: New Owners Confront Old Issues by Mark Lewis

From The Ojai Quarterly, Spring 2011 issue.

Most Ojai visitors arrive from the south on Highway 33 and turn right at the Y, heading toward the Arcade or the Ojai Valley Inn. But there was a time, not all that long ago, when many of these drivers would turn left instead, and smile gratefully at the highway marker proclaiming that Wheeler Hot Springs was only six miles away.

Most Ojai visitors arrive from the south on Highway 33 and turn right at the Y, heading toward the Arcade or the Ojai Valley Inn. But there was a time, not all that long ago, when many of these drivers would turn left instead, and smile gratefully at the highway marker proclaiming that Wheeler Hot Springs was only six miles away.

“It was almost a pilgrimage for me,” said Arthur von Wiesenberger, co-publisher of the Santa Barbara News-Press, as he recalled his regular Sunday trek over Casitas Pass and up the Maricopa Highway to take the waters at Wheeler. “I looked forward to Sunday,” he said. “There was a special energy there. I’d come back and face the week rejuvenated.”

Wheeler nostalgia is not confined to out-of-towners. Many local residents flocked to the resort to soak in its spring-fed hot tubs and enjoy a massage, followed by dinner and perhaps a jazz concert. “It was awesome when it was open,” recalled Jerry Kenton, co-owner of the Deer Lodge. “I used to go there on dates. It was great.”

When the resort closed in 1997, many people assumed that it would eventually reopen under new management. But a decade passed and nothing happened. Then, late in 2007, Wheeler began to show signs of life.

No announcement was made, but the resort had acquired new owners: Daniel Smith, a dentist who lives in Malibu and practices in Agoura Hills, and his wife, Maureen Monroe-Smith, who according to her Linked-In profile is an editorial assistant at Momtastic.com and the owner of Zuma Canyon Vineyards. For a while, to judge from the construction activity at the site, they seemed to be putting a lot of money into the place. But three-and-a-half years later, Wheeler has yet to reopen, and the new owners have yet to make their plans public.

“They try to keep it real private,” said Kenton, who co-owns a rental property right across the highway from Wheeler. “He [Smith] doesn’t want any publicity.”

The Kenton property is listed for sale with Sharon MaHarry of Keller Williams Realty, so MaHarry is often on the site. She said she never notices any activity at Wheeler, and has no idea what the Smiths have in mind.

“It’s a mystery to everybody in town,” she said.

Nevertheless, Smith was reasonably forthcoming when the Ojai Quarterly telephoned him last October to ask about his plans.

“We’ve been doing a tremendous amount of work to improve the property,” he said. “Unfortunately, the county has made it extremely difficult to re-open it.”

Smith said he would consider doing a sit-down interview on the Wheeler site. But when we got back to him a few weeks later to set it up, he asked us to hold off on our story.

“We’re at kind of a crucial point here,” he said. “At this stage, I don’t really think we want to put people on the property. What we’re doing is not really defined yet. We’re just not sure on direction yet.”

If the OQ would wait for a month, Smith said, he would tell us what was going on. So we waited more than a month, until January, and then we called him back. He did not return our calls.

It seems that the Smiths have run into a bit of bad luck at Wheeler. (See below.) But they are hardly the resort’s first owners to find themselves in this predicament. For more than a century, Wheeler Hot Springs has been luring visionary developers into the Santa Ynez Mountains only to break their hearts. Yet Ojai would not be what it is today without Wheeler, and the other hot-springs resorts that once graced the area. Lanny Kaufer, whose family operated Wheeler on and off from 1969 through 1993, notes that the resort will continue to loom large in Ojai’s history, even if it never reopens.

“The hot springs were the major draw that brought people to Ojai in the first place,” he said. “That’s what put Ojai on the map.”

Deer Hunter Discovery

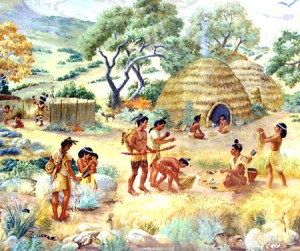

The Chumash phrase for hot springs translates into English as “tears of the sun.” It is often assumed

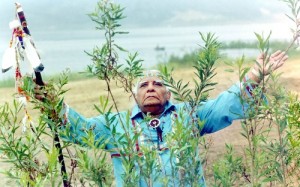

in Ojai that the Wheeler hot springs were sacred to the Chumash, but this cannot be confirmed: No archeological evidence for the Indians’ presence at the site has turned up thus far, and Chumash elder Julie Tumamait-Stenslie knows of no ancestral stories about the springs that have been passed down to her generation.

“The stories were lost,” she said. “We don’t know of anything documented. You want to trace legends and lore, but I’ve always come up to a dead end.”

Nevertheless, there was a Chumash village nearby, so it seems reasonable to theorize that the Indians knew of the springs, and that they considered the site a special place. There are those in Ojai who would go further, and assert that a Chumash curse afflicts anyone who tries to exploit the springs for commercial purposes. Tumamait-Stenslie said she does not know whether her ancestors put a hex on the place. What she does know is that over the years, the site has been extraordinarily unlucky for its would-be developers, and for other people as well.

She did not name names, but anyone who delves into Wheeler’s tangled history can identify many people who came to grief there — beginning with Wheeler C. Blumberg, for whom the springs are named. Wheeler was born in Clarence, Iowa in 1863. His father, Abram, was a lawyer. When Wheeler was 9, the family moved to Los Angeles for the sake of his mother’s health. She had read a book by the travel writer Charles Nordhoff, who touted Southern California’s climate as a cure-all. When her health failed to improve in L.A., she and Abram decided to try their luck at a new town site that R.G. Surdam was developing in Ventura County.

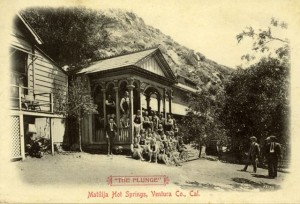

These were the great days of the famous spa towns such as Vichy, Marienbad, and Saratoga, where upper-crust tourists “took the cure” by soaking in thermal springs and sipping mineral water. Surdam no doubt had pricked up his ears in 1872 when he heard that hot springs had been discovered in Matilija Canyon. Someone else already was developing a health resort at the springs, but Surdam was free to found a town in the nearby Ojai Valley. He found a useful ally in Abram Blumberg, who agreed to build a hotel on the present site of Libbey Park. It was Wheeler’s mother who suggested naming the town Nordhoff, in honor of the writer. But the Blumbergs did not linger long in the town they co-founded. By 1887, Abram had sold the hotel and opened his own health resort, Ojai Hot Springs, in Matilija Canyon.

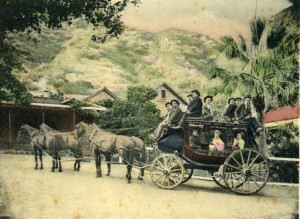

Abram advertised his springs far and wide as a cure for pretty much whatever ailed you, including syphilis and cancer. Wheeler drove the stagecoach that met their guests at the train station in Ventura and brought them to the resort. Wheeler was notorious in Nordhoff for his reckless driving. “Women and dogs had to scramble out of the way when he came barreling through,” said Wheeler’s grandniece Ginger Morgan.

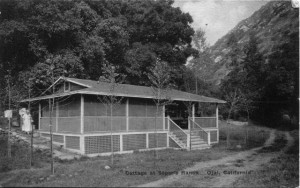

The road from Nordhoff to Matilija Canyon terminated at Lyon Springs, a smaller resort further up the canyon from Abram’s place. Beyond that point, there was nothing but an old Indian trail into the mountains. Wheeler Blumberg went up that trail with a rifle one day in 1888, and shot a deer near the North Fork of the Matilija Creek. The deer hit the ground near a bubbling hot spring. A second hot spring burbled nearby. Right there and then, in the middle of that unspoiled wilderness, Wheeler had his epiphany. He filed a homestead claim on the springs site; extended the road from Lyon Springs to his new property; and installed a spring-fed swimming pool, a bathhouse, and fourteen guest cabins. By 1891, Wheeler’s Hot Springs was open for business.

The springs were not the only attraction: Wheeler also offered fishing, hunting, camping, trail riding, swimming, and nightly dances. He even used hydropower from the creek to power his own electrical plant, which bathed the resort in electric light while the rude village of Nordhoff still got by with kerosene lamps.

Wheeler’s Hot Springs was a success from the start. But in 1894, Wheeler began to behave erratically. “It seems that he thought his wife’s heart was on the wrong side and he began

Wheeler’s Hot Springs was a success from the start. But in 1894, Wheeler began to behave erratically. “It seems that he thought his wife’s heart was on the wrong side and he began

pounding on her chest to put it right,” wrote Patricia L. Fry in The Ojai Valley: An Illustrated History. Wheeler was committed to an insane asylum, but he soon recovered and was back at his resort.

The Blumberg family sold Ojai Hot Springs after Abram’s death in 1899. (It was later renamed Matilija Hot Springs, and it’s still there, although currently not open to the public.) Wheeler held on to his own resort, which continued to prosper. It was not all smooth sailing: In 1904, the Anti-Saloon League of Southern California caused a sensation when it engineered Wheeler’s arrest for selling liquor without a license. But those temperance crusaders could not keep him down for long. He built a sizeable house on a cliff overlooking his resort, and tried to persuade his adult children to live there with him and be his partners.

“I don’t care to have outsiders in with me, so I thought it best if it all seemed satisfactory to all of you to incorporate it in the family,” he wrote to his eldest son, Clarence.

But then Wheeler suffered another breakdown — and this time, it made news all over Southern California.

“Wheeler Blumberg, proprietor of the springs bearing his first name, has been a raving maniac in the hands of the sheriff since he was incarcerated in the county jail yesterday morning,” the Los Angeles Times reported on May 21, 1907. “Blumberg is a desperate man, and for days he has produced a reign of terror at his springs resort, where he locked himself in his room with two or three guns and pistols and with big knives. He shot 15 holes through the walls of his room, and would occasionally make sorties outside, when everybody about the place would take to the hills.”

A posse managed to capture Blumberg alive and bring him to Ventura, where he was stuffed into a straitjacket, heavily sedated, and strapped to a couch in a padded cell. The sedative had little effect: According to the Times, he continued to scream at the top of his lungs and strain desperately against his bonds until the following morning, when he died “from utter exhaustion.” He was 43 years old.

The Fires Up Above

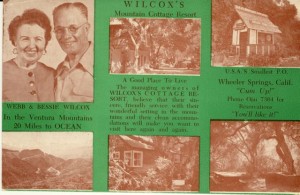

After Blumberg’s death, the resort’s name contracted from “Wheeler’s” to “Wheeler,” as control passed to the founder’s son-in-law. Webb Wilcox was a young man from Illinois who had hired on in 1903 to drive the resort’s stagecoach. Two years later he married the boss’s daughter, Etta Blumberg. By 1913, when he was named postmaster of the newly established Wheeler Springs Post Office, Wilcox was clearly the man in charge.

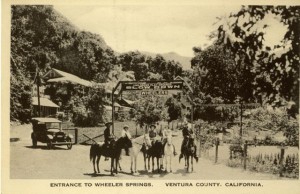

The stagecoach era had passed. The railroad now delivered the resort’s guests all the way to Nordhoff, where they boarded a big Stanley Steamer motor coach for the short, scenic drive out to Wheeler Springs. The resort was thriving and so was the town, and this was not a coincidence.

“Being situated as Nordhoff is, the railway station for the three great health resorts — Matilija Hot Springs, Lyon Springs, and Wheeler Hot Springs — our beautiful and fertile valley gets a great deal of advertising and comes to the notice of many people who would not otherwise come this way,” The Ojai newspaper noted in 1913.

Wheeler clearly was the newspaper’s favorite: “Situated in another canyon, a little at one side of the main Matilija Canyon, but reached by a pretty mountain road, is the famous Wheeler Springs, under the management of that prince of good fellows, Webb Wilcox. Hot and cold mineral springs, fine trout fishing, commodious camp grounds and good treatment have been prime factors in establishing the fame of Wheeler’s Springs. While this place has not been open as a resort for so many years as the other two, it has been popular from the first. As seasons pass the crowds increase, and the resort is becoming more and more popular for winter guests.”

Then in June 1917, a carelessly maintained campfire near the resort touched off the epic Matilija-Wheeler Fire, one of the worst forest fires in California history. The town, which had just changed its name to Ojai, almost saw its brand-new Arcade go up in flames.

“With 200 men we worked like demons for five days and five nights before we got the best of that blaze,” the legendary forest ranger Jacinto Damien Reyes recalled years later. “But it was not until 30,000 acres was a blackened waste. In that fire we had a terrific battle to save the buildings of the Wheeler Springs resort and while we were busy at that the fire burned out of the forest and into the town of Ojai.”

The flames roared over Nordhoff Ridge and down into the town, but were stopped short of the Arcade. Even so, the fire killed five people, destroyed 70 houses and other structures, and forced many terrified residents to flee the valley in panic. Future historian Walter Bristol recorded his reaction: “The glow of the flames reflected by the smoke-filled air made the scene an inferno never to be forgotten by those who witnessed it.”

Ojai rebuilt, the forest regenerated, and Wheeler Springs continued to attract tourists from all over Southern California–and sometimes from further afield. During the 1920s, heavyweight-boxing champion Jack Dempsey stayed there while he trained at Pop Soper’s, just down the road.

In 1926, Webb Wilcox reaped a potential bonanza when the state agreed to pay for the proposed Maricopa Highway to connect Ventura with Bakersfield. The new road would allow Wheeler to draw visitors from the north as well as the south. Thinking big, Wilcox sold a half-interest in Wheeler to R.F. Just, proprietor of the Battle Creek Sanitarium of Long Beach. They planned to build a similar sanitarium at Wheeler. Apparently that plan fell through, because in August 1929 the Times reported Wheeler’s sale to resort developer L.W. Coffee, the future founder of Desert Hot Springs.

Coffee envisioned Wheeler as a mountain resort along the lines of Lake Arrowhead. He drew up plans to subdivide part of the property for vacation homes. But his investment was poorly timed. Two months later, the stock market crashed, the nation tumbled into the Great Depression, and Coffee’s plans came to naught. In 1934 the Times reported that Wheeler was “back under sole management of Mr. and Mrs. Webb Wilcox.”

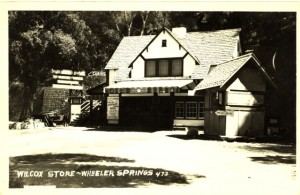

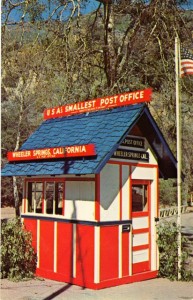

Not for long. With the recently completed Maricopa Highway running right through the middle of Wilcox’s property, he found himself in possession of some prime highway frontage. In 1935, he built a new “Cottage Resort” just east of the road. Essentially a motel, it consisted of a handful of cottages perched precariously atop a terrace carved into a steep hillside, supported by a massive retaining wall that reared up dramatically from the highway. At the base of that wall he built the Webb Wilcox Cafe, and next to the cafe he installed his tiny Post Office building, which was little more than a glorified shack. (“Ripley’s Believe it or Not” designated this structure “the U.S.A.’s smallest Post Office,” and Wilcox — ever the promoter — placed a sign to that effect on its roof.)

Having created a new fiefdom east of the highway, Wilcox disposed of his interest in the old resort, which was on the west side of the road. And with that, Webb Wilcox parted ways with Wheeler Hot Springs. By 1943, if not earlier, it had been acquired by one L.E. Needham, who apparently had little luck with it.

Wheeler was hit hard by the great flood of 1938, and again by World War II, when gasoline rationing kept many would-be tourists at home. (It is said that during the war years, an enterprising Nordhoff High School student operated a weekend bordello in the resort’s vacant cabins.) When the war ended, the picture seemed to brighten, due in part to the construction of Matilija Dam. Wheeler faced less competition after the new dam obliterated Lyon Spring and blighted the prospects of Matilija Hot Springs. But the polio scare was a severe blow, because people were afraid to patronize resorts with swimming pools.

A bigger blow was imminent. Three decades had passed since the 1917 fire, and the brush had grown back. In September 1948, a butane leak in a shed near the Wheeler swimming pool touched off another catastrophic blaze. Once again, the citizens of Ojai looked up to see flames descending upon them from Nordhoff Ridge. A sudden shift in wind direction saved the town from destruction, but not before 13 homes were destroyed, and a man died of a heart attack while fighting the flames.

Wheeler Springs survived, but the resort was on a downward spiral. In 1953, a retired Los Angeles produce wholesaler named Sam Sklar acquired control and announced plans to put up a 400-room hotel. It was never built, and Sklar soon went bust. The next owner was none other than Art Linkletter, the famous radio and television personality. Inspired perhaps by the opening of Disneyland in 1955, Linkletter spent a lot of money on a new Wheeler Springs attraction called Kiddie Land, adding rides and other features that appealed to children. He failed to prosper.

“We saw Linkletter several years after at a party and asked him about Wheeler,” wrote Fred Volz, the longtime Ojai Valley News editor, in a column. “He just grimaced, turned away and started to talk to a friend. We later heard he dropped a bundle.”

Meanwhile, Webb Wilcox continued to preside over his “Cottage Resort.” Etta Blumberg Wilcox died

in 1941, and Rose Blumberg (Wheeler’s widow) in 1947, but the Blumberg clan was still represented in the neighborhood by Etta’s younger brother Carl, who lived in Wheeler’s old house on the cliff. “It was filled with antiques,” said Ginger Morgan, who recalls many family gatherings there. “It was nice.”

The house passed out of the family after Carl’s death in 1959. As for Wilcox, he finally retired in 1960 and moved into a trailer house near his old cafe, which now had new owners. None of his children had stayed in the area, so when Wilcox died in 1962 at the age of 81, it marked the end of an era. That same year, Wheeler Springs lost its status as a U.S. Post Office, due to a lack of business. The resort was still open, but its glory days were long past.

The Turning of the Wheel

For Evelyn Landucci, it was love at first sight. The year was 1969, and Evelyn, a devotee of the Human Potential Movement, wanted to establish a New Age “growth center” in Southern California. She and her husband, Frank Landucci, had driven up from Los Angeles to check out Wheeler Hot Springs as a possible site.

“My mother had been going to Esalen,” said Lanny Kaufer, Evelyn’s son from an earlier marriage. “She envisioned an Esalen South.”

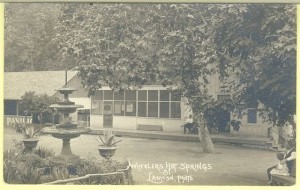

The Esalen Institute in Big Sur was an old hot springs resort reborn in the early ’60s as a New Age retreat. Wheeler Springs in 1969 was mostly a trailer park plus a few dilapidated relics left over from the resort’s heyday, including a lodge, a cafe, a dancing pavilion, the swimming pool — and Webb Wilcox’s old postal shack, still topped by that sign proclaiming it “the U.S.A.’s smallest Post Office.” All in all, the resort was not an impressive sight. But the hot springs still burbled, the mountain scenery remained unspoiled, and some of the buildings looked salvageable.

“It seemed like the perfect spot for what they had in mind,” Kaufer said.

The karma was not perfect, given that Wheeler’s previous owner, Rollen Haslam, had shot himself to death at the resort a few years earlier. But the Landuccis took the plunge and acquired Wheeler Springs from Haslam’s widow. (Or technically from Art Linkletter, who still owned the mortgage.) A few weeks after escrow closed, the canyon was scoured by the great flood of ’69, which turned the creek into a raging torrent. When the waters receded, the resort was pretty much gone.

The Landuccis soldiered on, with help from the Small Business Administration. The SBA was dubious about funding a “growth center,” so instead the Landuccis rebuilt the ruined lodge as a gourmet Italian restaurant, which opened in 1975. Their children — Lanny, Michael, John and Gilda — pitched in to help. “It was a family operation,” said Lanny Kaufer, who waited on tables.

One of their regular customers was the rock star Jimmy Messina (of Loggins & Messina), who owned a ranch in the area. Messina urged the Landuccis to divert the hot springs water from the old swimming pool to a spa stocked with redwood tubs. “They’re all the rage these days,” he said. The Landuccis took his advice and added spring-fed tubs to the mix. Between the restaurant, the spa, and the big dances they hosted, Wheeler Hot Springs was now back on the map, especially for people who lived in the area. But the Landuccis needed to expand their reach.

“The business was doing well, but not nearly as well as it could have in its fully realized form as a resort,” Kaufer said. “They had always intended to have overnight guests and knew that was the key to success. Without it, Wheeler was predominantly a weekend business. And although they were making slow progress, it was a time-consuming, expensive process to try to get the county’s approval for their plans.”

Enter Roger Bowman, a Wheeler regular with an entrepreneurial bent. He offered to help the Landuccis find a buyer for the place, and ended up buying it himself around 1980.

He put a lot of money into retooling the restaurant and spa as “Bowman’s at Wheeler Hot Springs.” His then wife, Ojai clothing store owner Barbara Bowman, contributed her designer’s touch to the project. “When we had it, it was fabulous,” she said.

The Bowmans emphasized the site’s presumed connection to the Chumash. They marketed their restaurant and spa as “built on an ancient Indian healing ground,” where the Chumash once visited the springs “to cleanse and purify their spirits.”

“The thought to incorporate an Indian motif had nothing to do with marketing,” Roger said. “It was the natural feeling of the property. This is where Barbara came into play. She was able to capture and embellish that feeling. It wasn’t just using an Indian motif. It was to be much higher order, much more spiritually oriented, than that.”

Early on, while researching the Indian connection, Roger encountered a devotee of Chumash lore who warned him that the place was cursed. This amateur shaman offered to help Roger ward off the evil spirits by performing an esoteric ceremony involving an eagle feather and an abalone shell. Roger politely declined.

“Do I believe in curses? Well, obviously I don’t, because I ignored the rite and went into it,” he said. “Maybe I should have listened to him.”

The Bowmans’ version of Wheeler Springs offered a vivid contrast with their neighbor across the highway. The old Webb Wilcox Cafe had long since evolved into the Wheel, a lively roadhouse operated by Mary Sullivan. It too was packed on weekends, especially on Sunday afternoons when Jerry Pugh’s rock band, Studebaker, played its regular gig. “I played there for 11 years straight,” Pugh said. “It was good times.”

The Wheel’s clientele mostly arrived on motorcycles, and they drank a lot of beer and ate a lot of Wheelburgers. They also made a lot of noise, especially on certain holidays. The neighbors noticed.

“On St. Patrick’s Day you knew you wouldn’t get any sleep,” said Joe Barthelemy, the proprietor of Serendipity Toys. Joe and his wife, Lilly, had bought the old Blumberg house in 1977, expecting to raise their family in tranquil surroundings. Lilly had enjoyed playing pool in the Wheel back in the early ’60s when she was a teenager. Those were the days when Johnny Cash had a house down in Casitas Springs, and he is said to have been a regular at the Wheel’s bar. But by the ’80s, the Wheel was a much noisier — and rowdier — place. “It just got worse through the years,” Lilly said.

The Wheel was a less-than-ideal neighbor for Roger Bowman as well, but he had a bigger problem. His restaurant and spa were doing well, but the 85-acre Wheeler site was very expensive to maintain. “Just to clean the palm trees cost $10,000,” Barbara Bowman noted. So, like the Landuccis before him, Roger Bowman sought the county’s approval to take in overnight guests. His plan was to put in yurts, in keeping with the resort’s esoteric motif. “We needed to expand to have the property be financially viable,” he said. But county officials resisted, due to concerns about waste disposal.

Bowman also had to fend off a wrongful-death suit involving a gruesome after-hours accident at Wheeler in which a fast-moving car ran into a chain strung across a roadway, with fatal results. Bowman said he ultimately prevailed, but fighting the lawsuit took its toll. As his Wheeler losses mounted, Bowman grew increasingly frustrated. “It was a lot of work and a lot of money,” he said. Around 1983 he shut it down and reconveyed the property back to the Landuccis, to their chagrin.

In retrospect, Bowman thinks that amateur shaman may have had a point about the Wheeler site. “It has an ongoing history of people encountering disasters there, and I was just one of a series of them,” he said. Yet in a way, he was lucky: “I only lost money.”

The Curse Continues

The Landuccis were not thrilled to have Wheeler Springs back on their hands. But Evelyn’s youngest son, John Kaufer, stepped into the breach. Having worked in the film industry, he envisioned a resort that would appeal to Hollywood types and other well-heeled Angelenos. The spa reopened in 1985, and among the employees was Julie Tumamait-Stenslie.

“I was a receptionist there,” she said. “John wanted to build cabins. He was starting to get the restaurant on the map and get the L.A. crowd up.”

According to an Ojai Valley News account, John signed the papers to take control of Wheeler on July 1, 1985. Just a few hours later, people at the resort began smelling smoke. Tumamait-Stenslie was there that day with her then-husband Jerry Pugh. “We had just had a hot tub and massage,” Tumamait-Stenslie recalls. “We looked up and saw a wall of flames coming down from the north.” They raced across the highway to rescue Studebaker’s equipment from the Wheel.

The Wheeler Fire, as it is known to history, was touched off by an unknown arsonist just north of the resort. Once again, as in 1917 and 1948, a fire that began at or near Wheeler Hot Springs quickly burned its way to the top of Nordhoff Ridge and threatened Ojai with destruction. Firefighters put up a desperate fight and the town was saved, with no loss of life. But at least one ghost was evicted from his old haunt. Among the structures that burned was Wheeler Blumberg’s old house, the one he had shot full of holes back in 1907. As the flames closed in, Joe and Lilly Barthelemy and their family were forced to evacuate. When they returned the next day, only the chimney was left standing.

Wheeler Springs itself survived (as did the Wheel), so John Kaufer proceeded with his plans. The restaurant reopened with a new feature: performances by well-known jazz musicians. “And it really took off, and began to attract people from Los Angeles,” Lanny Kaufer said.

But the Wheeler Fire had not yet claimed its last victims. On a rainy Friday afternoon in October 1987, a problem developed with the line that supplied the resort with water from a cold spring in the hills above. John and two employees, Cristina Gilman and Kenny Farchik, trudged up to take a look. Looming over them was a big oak tree. It looked healthy from the front, but its uphill side had been gutted by the fire of 1985. As John and his helpers grappled with the water line, they heard a loud crack as the oak abruptly collapsed on them. “The tree leaped like a dragon,” Farchik told the News. Gilman was killed instantly. John died the in the hospital the next day. He was 31 years old.

“From that point on, my parents just wanted to sell the business,” Lanny Kaufer said.

Enter Tom Marshall. As described in a Los Angeles Times article in 1993, Marshall was a Brooklyn native with a checkered past as a stockbroker and restaurant promoter. His biggest claim to fame was as a co-founder of Broadway Joe’s, a short-lived chain of restaurants associated with Joe Namath. By 1987, Marshall had reinvented himself as a Hollywood producer, although one with few films to his credit. That fall, not long after John Kaufer’s death, Marshall heard about Wheeler Hot Springs and drove up from L.A. to steep himself in a tub. He was smitten by Wheeler’s beauty and serenity–and by its possibilities. After a long courtship, he struck a deal with the Landuccis to sell him the place in 1993, although they retained a major financial interest.

Marshall, like all his recent predecessors, wanted to restore Wheeler to its original status as a full-fledged destination resort. His was the same vision, essentially, that had inspired Wheeler Blumberg when he first stumbled over the hot springs a century earlier. Marshall wanted to add cabins, a banquet hall, and meeting rooms; expand the restaurant and spa; and build a bottling plant so he could sell Wheeler-branded mineral water. Arthur von Wiesenberger, who was (and still is) a bottled-water expert, did some consulting for Marshall at the time. “I think Tom was trying to bring [Wheeler] to a different level,” von Wiesenberger said: Less rustic, more upscale.

That would take money. Marshall’s first plan was to sell stock in his venture. When that didn’t pan out, he turned to private financing. His biggest and least likely investor was the Dewar Foundation of Oneonta, N.Y. Dewar had been founded decades earlier by an heiress whose money came from the company that evolved into IBM. In 1993, Dewar’s guiding spirit was Frank Getman, an Oneonta mover and shaker who shared Marshall’s enthusiasm for Wheeler’s potential. Getman steered $1.5 million of Dewar’s money into Wheeler, and threw in some of his own.

But Marshall, like his predecessors, encountered resistance from Ventura County officials, and meanwhile his cash-flow problems mounted. At some point he apparently stopped paying his withholding taxes. Then his paychecks started bouncing. In the fall of 1996, he was charged with passing bad checks to his employees, and the Internal Revenue Service seized Wheeler Springs to auction it off for unpaid payroll taxes.

To forestall that move, Marshall had Wheeler declare bankruptcy.

According to news reports at the time, Marshall resolved the bad check charges by pleading guilty to one misdemeanor count and paying a $330 fine. He later left town, and the Ojai Quarterly could not determine his current whereabouts.

Several people interviewed for this story portray Marshall as the villain of the piece, and wonder how he managed to evade prison. His former attorney, Paul Blatz, is more charitable. “I don’t think he was a crook,” Blatz said.”I think he just got over-extended.”

The resort limped along under Chapter 11 status until Jan. 23, 1997. On that day the federal bankruptcy trustee shut it down, putting some 60 employees out of work. “The cash-flow problem was difficult,” the trustee’s attorney told the Ojai Valley Times. “That doesn’t mean the place will be closed forever.”

Enter Eliot Spitzer

When the dust settled, the new owner of Wheeler Hot Springs was the Dewar Foundation, which had no interest in running a resort. Dewar immediately starting looking for a buyer, with no success. Meanwhile, Frank Getman ran into the Wheeler curse in the person of New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer. In June 1999, Spitzer’s office sued three Dewar board members, including Getman and his son Michael, for allegedly mismanaging the foundation’s assets by investing in Wheeler Springs.

“It is the responsibility of my office to protect the assets of charities which are created to do good in our communities,” Spitzer said in a press release. “Because these individuals acted irresponsibly, they do not deserve, nor can they be trusted to oversee the millions still left in the care of this foundation.” In particular, Getman and his fellow board members were accused of “imprudent loans to a risky start-up mineral water business in California–Wheeler Hot Springs.”

This was a humiliating experience for Frank Getman, a prominent citizen in Oneonta. In 2002 he resolved the matter by resigning as Dewar’s president and agreeing to pay the foundation $500,000. The settlement included a provision that would allow Getman to recoup some of that money if Wheeler ultimately sold for more than $2 million. That was considered highly unlikely: Spitzer’s office said the Wheeler property was not worth more than $750,000.

Years passed, and Spitzer found bigger fish to fry. His high-profile probes of Wall Street heavyweights propelled him into the New York governor’s mansion. Meanwhile, Dewar kept trying to unload its Wheeler white elephant. According to Michael Getman, they came very close to a sale several times over the years, but something always went wrong at the last minute.

Meanwhile, rumors periodically swept Ojai that some potential white knight was kicking the tires out at Wheeler Springs. “I heard a brewing company was going to buy it,” Julie Tumamait-Stenslie said. “Then I heard Oprah was going to buy it.” One rumor she knew wasn’t true was that the Chumash would buy Wheeler with profits from their Santa Ynez casino. “They’re not interested,” she said.

At one point, Roger Bowman was contacted by a friend who asked his opinion of Wheeler as a potential investment. Bowman said he described the site’s fraught history, “and concluded that from my point of view, the property has certain barriers it presents to owners. I have concluded that this was due to Indians protecting against commercial enterprise on their ritual ground.” His friend did not pursue a deal for Wheeler.

For a few years, Mary Sullivan at the Wheel had that stretch of Maricopa Highway all to herself. In 1998 she brought back Studebaker as the house band, but that didn’t last long. Jerry Pugh did not care for some of the shady characters who now hung around the Wheel and its cottages. “It wasn’t the same element,” he said. Sullivan was now over 70 and in declining health. She seemed less up to the challenge of running a respectable biker bar, and things began to get out of hand. “There were some horrifying things that happened at that place,” Tumamait-Stenslie said.

County health inspectors finally closed it down in November 1999 when they discovered that it no longer had a source of potable water. Sullivan apparently could not afford to fix the water problem so she retired, after 30 years at the Wheel. The property soon acquired a new owner, Bob Hope. (No, not that Bob Hope.) He and his wife, April, live with their family in a house up the hill from the bar. But the Wheel has never reopened.

Eventually, Wheeler Hot Springs acquired a new owner too. It sold in the fall of 2007 — for $3.3 million. Improbably, the Dewar Foundation ended up making a tidy profit on its investment. Frank Getman died in 2009, but not before seeing his faith in Wheeler vindicated. (Getman had the further satisfaction of seeing Eliot Spitzer brought low by the sex scandal that forced him to resign as governor in 2008.)

Which brings us back to Dan Smith and Maureen Monroe-Smith. Like Marshall and Bowman before them, the Smiths first encountered Wheeler Springs as customers rather than as potential investors. “My wife and I used to go there all the time when it was open,” Smith told the OQ last fall (before he stopped returning our calls).

Disappointed when Wheeler closed, the Smiths eventually became curious as to why it had never re-opened. Maureen did copious research, and the couple ended up buying the place. Dan said their plans for it include making Wheeler energy self-sufficient by generating their own electricity at the site. They also plan to market bottled water with the Wheeler Springs brand. And, unsurprisingly, they want to add overnight accommodations.

But before they can even reopen the restaurant, they will have to bring the resort up to code. “They would have to put up some sort of sewage treatment plant,” said Steve Offerman, an assistant to County Supervisor Steve Bennett.

Working with the county on this issue “has been a very difficult process,” Smith said, echoing the complaints of previous owners. But county officials note that they have received no formal application regarding Wheeler. “The ball’s still in their court,” said Winston. “It is all dependent upon what they propose.”

Across the street, Bob and April Hope have the same problem as the Smiths. They want to reinvent the Wheel as a bed-and-breakfast place, and Bob said he has long since fixed the potable water problem that drove Mary Sullivan out of business. But to reopen the Wheel would require a new septic system, and the Hopes and county officials do not see eye-to-eye on how that should be accomplished. The Hopes want to use a kind of septic system which they said is legal in Malibu and in Santa Barbara County, but not here. “Ventura County won’t even look at it,” Bob said bitterly.

In separate conversations, both Bob Hope and Dan Smith alluded to the possibility that they might resolve their problems by combining their properties (and thus reuniting what Webb Wilcox tore asunder back in 1935). “If they were united it would be easy,” Smith said. But he scoffed at the $3 million that Hope (at the time) was asking for the 40-acre Wheel property. “It’s a little unreasonable,” Smith said.

That’s how things stood last October, when Smith (in a second, much shorter conversation) declined to provide a tour of his property and (as it turned out) cut off any further communication with the OQ. Four months later, the Smiths’ neighbors know of no new developments since the fall concerning Wheeler Springs. Which is not to say that there have not been any.

“No one really knows what’s happening across the street,” April Hope said. “They’re very, very tightlipped.”

Maureen Monroe-Smith finally broke radio silence in mid-January when she responded to a Facebook message. But her reply only added to the mystery surrounding Wheeler. At the moment, she wrote, “there is really nothing for us to report back to you on any future plans for the property. [And] our partners in this property are not granting site visits to anyone at this time.”

Who are these partners? Apart from the Smiths, the only other person listed in Ventura County property records for the Wheeler address is Rickey M. Gelb, a prominent commercial real-estate developer based in the San Fernando Valley. When contacted by the OQ, Gelb said that he owns 50 percent of Wheeler Hot Springs LLC, while the Smiths, who are the managing partners, own the other 50 percent.

The three partners originally acquired Wheeler Springs at the height of the real estate bubble in 2007, only to see the economy tumble into the Great Recession. Gelb said that after laying the groundwork for reviving Wheeler as a full-fledged resort, he and the Smiths hoped to bring in another partner “who has the expertise to bring it to the next level.” But the recession interceded, and now the project is “on hiatus.”

“I’m not sure what we’re going to do with it, to tell you the truth,” he said. “We don’t have the dollars to bring it to a finished product.”

Further complicating the situation, Gelb added, is that the Smiths have separated. “That did slow things down,” he said.

The Smiths decline to be interviewed, so there is no way to determine whether they would agree with Gelb’s assessment. Nor do they appear to have taken any of their neighbors into their confidence. So the mystery endures, and Wheeler Springs remains padlocked.

“It’s like a chess game,” April Hope said. “Everybody’s waiting to see how it plays out.”

Wheeler Springs Hopes Eternal

The highway sign is still there at the Y, but it tells a lie: Wheeler Springs is not really six miles away. For all practical purposes, there’s nothing there.

“It would be fantastic for Ojai if that thing came back to life,” Sharon MaHarry said. “People would come from all over, as they once did.”

To Barbara Bowman, the solution is clear: The county should ease up and work with Wheeler’s owners, “rather than putting stumbling blocks in the way.” She points to the Ojai Valley Inn, the town’s biggest employer and a magnet for visitors who spur the local economy. “That’s a huge draw for Ojai,” she notes. “We could use another one like it.”

Wheeler Hot Springs “could be an outstanding destination point,” she said. “It was a big draw in our day, and Ojai is much more famous now.”

But Julie Tumamait- Stenslie recoils from the idea of a Wheeler aimed at upscale out-of-towners. That would price out the locals. “Make it a place where anyone can come,” she said. “Build something that is actually community based and a healing center that can actually benefit people.”

If that sounds impractical, she said, then consider Wheeler’s track record: In recent decades, owner after owner has tried to turn the place into a full-fledged resort of one kind or another, and all have failed. “There it sits, with nothing going on. There’s something there that prevents it from becoming a 5-star place or a 4-star place.”

There’s also something there that keeps tempting new owners to try their luck, despite the history. Even if Gelb and the Smiths end up falling short, someone else will surely pick up the dice. Eventually, someone might even succeed in reopening the place. Then all the old Wheeler Springs regulars would come out of the woodwork and head up Highway 33, eager to reconnect with whatever it is that makes the resort special. Even after a 14-year hiatus, Wheeler still exerts its pull. Were it to reopen tomorrow, von Wiesenberger said, “I’d be coming back up there next week.”