Jeff Mann is among the Ojai Studio Artists participating in this year’s OSA group exhibit at the Ojai Valley Museum. In conjunction with the exhibit, we present Ojai Quarterly arts columnist Anca Colbert’s piece on Mann, which ran in the OQ’s Spring 2015 issue: Drawn to Drawing(s): Anca Colbert on Jeff Mann

The Mason Chronicles (2)

The San Antonio School

By David Mason

“Amid much rejoicing, San Antonio’s new school building was formally presented to the district last Friday night. The whole community has been watching with interest the erection of this attractive structure, which makes of the San Antonio corner another beauty spot for our valley.”

– The Ojai, April 8, 1927

The year was 1887, and President Grover Cleveland, in his first of two terms as president, was still enjoying his honeymoon with the former Frances Folsom. The White House was a hub of social activities, while in a little valley in California, a new school was being formed. The importance of this rather small school may not have made the national news, as the White House wedding had, but to the people of Ojai, it was another step in the development of the valley.

The San Antonio School was established in 1887 and was formed as an independent school district. An even smaller school, The Sagebrush Academy at the foot of the grade road, had closed down because most of the students lived in the upper valley and they wanted a school closer to home, so they had created the Summit.

The few children living in the East End of the valley were then left without a school to attend, except for some small private schools that were scattered around the area.

At first, the students gathered and held their classes under a large oak tree. Then an old granary that was no longer in use on a nearby ranch was put into operation as a classroom. Finally, three acres on the southeast corner of Grand Avenue and Carne Road were purchased from the Beers family for $25, and the first San Antonio schoolhouse was built. The schoolhouse was a lovely Victorian structure, put up in record time using volunteer carpenters, and when completed it was an impressive building, especially for such a small, rural community. It had a fancy bell tower and a flagpole with the American flag flying high in the sky.

Fred Udall Jr., an early student, wrote about his years in attendance at San Antonio School:

“Even the Pledge of Allegiance was simpler in those days, but we put a great deal of sincerity into saying it. As I recall, it went something like this: ‘I pledge allegiance to the flag, and to the republic for which it stands. One nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.’ Our teachers asked us to think about the words we were reciting as we faced the flag before starting the school day. We didn’t need to name the country in the pledge, we knew we were Americans.”

By the late 1920s, classes had outgrown the stately Victorian schoolhouse, so the school board commenced to make plans for building a new and larger school. The school board, wanting a special type of building, hired Roy Wilson, a Santa Paula architect.

Wilson came with his family to Los Angeles in 1902 and settled near the Arroyo Seco, in an area known today as Highland Park. Roy left school after the seventh grade and took various jobs to supplement the family’s income. One of those jobs was as a draftsman for local architect, Edwin Thorne, who inspired him to learn more about architecture, and Roy was persuaded to move to Berkeley to study at the university.

Upon his arrival in 1906, the great San Francisco Earthquake hit and destroyed much of the city. His formal education was abruptly cut short and through his help in the re-building of the city, practical experiences became his teacher.

In 1914, Wilson discovered the small town of Santa Paula, purchased 40 acres of land and planted a citrus orchard. He opened a small architectural office in Santa Paula, and in 1924 became the first licensed architect in the county of Ventura. Many of the outstanding buildings that add to the beauty of The Ojai are the creations of this talented man.

Among his structures are the Ojai Elementary School building; the Nordhoff High School campus, now Matilija Junior High School; Bill Baker’s Bakery; various buildings at Krotona; and the science building at The Thacher School. Many of our 1920s-style Spanish mansions are also the work of this great architect.

One of the San Antonio School trustees was originally from England, and he was in favor of the new building being built in the English Tudor style, because the style would then remind him of his homeland. The school board voted in favor of that style, so Wilson was instructed to design a building that would have the look of being English, in contrast to the more familiar Spanish style that was being used in

Ojai Valley.

When completed in 1927, the architecture was indeed unique, yet harmonizing with the surroundings, and would symbolize a school district within the community whose choice it was to preserve its own individuality, but whose earnest desire it was to work with the other buildings for the good of all. The interior of the building was roomy and pleasant and adequately equipped. The two classrooms, separated by a large folding divider, could be opened up to make an auditorium. The stage area was the largest in the valley at that time. The overall effect was delightful, and it served the East End of the valley well.

The school year of 1929 opened with an enrollment of 28 students in the entire school. When I went to school there, from 1949 to 1951, my class consisted of five students, two boys and three girls. My class, however, was not as small as my mother’s class. She attended San Antonio when it was still in the Victorian building, and she had two students in her class.

The little English Tudor school finally gave up its independence in 1965 and joined the Ojai Unified School District. The school building continues to bring a lot of joy to people in the Ojai Valley. The Ventura County Cultural Heritage Board wanted to declare this building a county landmark, but was turned down by the school board. Perhaps someday, this worthy building will have the honors bestowed upon it that it so rightfully deserves.

The above column originally appeared in The Ojai Valley News in 1999. Republished with permission.

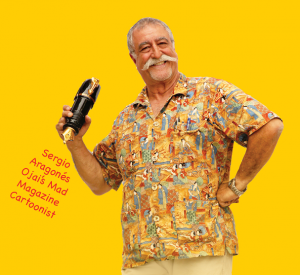

Ojai People: Sergio Aragones

Ojai’s Cartoonist in Residence

By Jerry Camarillo Dunn, Jr.

To look at him, you might think he’s just another guy loafing around an Ojai coffee shop, staring into space. But if you could peer inside his head, you’d see that he’s hard at work.

Sergio Aragones is a cartoonist.

That chortling you hear as he doodles on his napkin? It means Sergio just thought of another gag for MAD Magazine, where he’s been a creative force of nature for more than 50 years.

It all began in 1962, when the fledgling cartoonist left his home in Mexico to try his luck in America. He arrived in New York with twenty dollars in his pocket and a portfolio of funny drawings under his arm. After learning that cartoonists visited the city’s magazines on Wednesdays to sell their work, he started making the rounds. “Your cartoons are crazy!” everyone said. “You have to take them to MAD. That’s where they belong.”

MAD was the nation’s top market for silly pictures, but the 24-year-old cartoonist screwed up his courage and appeared at the magazine’s office. The editors took his samples into a little room . . . and there was a deafening silence. But at last Sergio heard guffaws of laughter echoing off the walls. His cartoons were a hit, and they’ve been off the wall ever since.

The editors assembled some of Sergio’s wordless gags into a two-page story about the U.S. space effort. One drawing showed a space capsule in orbit with a dismayed astronaut in the window, watching a paper airplane sail past.

“I wanted to sell MAD more drawings,” Sergio recalls, “and I saw all the empty areas around the borders of the pages.” So began the legendary “Marginals,” gags that Sergio tucks into the white spaces throughout the magazine. The only thing not marginal is the humor.

Sergio characterizes himself as a “writer who draws,” and each Marginal is a short story in itself — like the drawing of a bearded psychiatrist so absorbed in taking notes that he doesn’t notice his patient leap off the couch and out the window.

MAD’s editors thought the Marginals were a cute idea but couldn’t last long. They told Sergio, “Well, we’ll publish them until you run out of ideas.” Since then his work has appeared in every issue except one. (“The post office screwed up.”) Over nearly five decades, he has drawn thousands upon thousands of his trademark wordless gags.

In fact, Sergio is reputed to be the world’s fastest cartoonist. He is definitely the most honored, having won every major award including the National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben, which is the Oscar of the field.

Even as a schoolboy in Mexico, where his father eventually relocated the family after leaving Spain for France during the Spanish Civil War, he was always drawing funny pictures in class, which entertained his pals and exasperated the teachers. (“Sergio, pay attention!”)

He also developed his imagination by playing make-believe, but in a way most kids could only dream about. His father was a movie producer at Mexico City’s Estudios Churubusco. “Whatever movie they were shooting, that’s what I played. If it was cowboys and Indians, I’d go to the prop department and get myself a big hat and a set of guns,” Sergio says. “The western town was my favorite. In front of the cantina was a railing for the cowboy actors to tie up their horses. When there wasn’t a movie being made, I loved to go there and challenge invisible bad guys. I’d come banging out through the cantina doors, get shot, flip over the railing with my legs in the air, and land in the dusty street. Then I’d do it again and again — because I was a kid!

“Your imagination really goes wild on a movie set. I think it helped my cartooning later on, in thinking up ideas.” His formal schooling continued at the University of Mexico, where Sergio studied architecture. “But my friends were actors, artists, and directors,” he says. “I learned pantomime from Alexandro Jodorowsky,” the avant-garde filmmaker. “I wanted to study pantomime so I could apply it to my cartoons. I love cartoons without words! They’re like silent movies.”

When Sergio announced his intention to be a cartoonist, his father was terrified because cartoonists don’t always make a great living. At age seventeen, though, Sergio started selling his work professionally when an art teacher sent his drawings to the Mexican humor magazine Ja-Ja. “I realized that cartoons have to be published for people to enjoy them,” he says. He also realized that America offered a much larger market than Mexico for his drawings.

Soon after his arrival in the U.S., Sergio began writing scripts for comic books — ranging from House of Horrors to Young Romance — for the top publisher in the field, DC Comics. By the early 1980s, he decided to launch his own comic book.

Groo, the Wanderer is a takeoff on the “sword and sorcery” genre, particularly Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian. Sergio’s writing partner, Mark Evanier, describes the main character as “an ugly, large-nosed buffoon of surpassing ignorance who constantly misunderstands his surroundings. Possessed of superlative skills in swordsmanship (the only task in which he’s remotely competent), he delights in combat but . . . unfortunately he is also indiscriminate and incredibly accident-prone, and despite generally good intentions causes mass destruction wherever he goes.”

With Groo, Sergio took up a new artistic challenge. He explains the differences between his two chosen formats: “Comic books are a mix of storytelling and drawing — sequential art, panel after panel. A cartoon is a compressed idea; you simplify it to the maximum. You can tell a story in a whole comic book, or take panels off until you have just one. Then take the dialogue off, and in one panel, without words, you have a whole story! That’s why I think pantomime is very impressive.

“A comic book, on the other hand, is like a mini-movie. You write, direct, act it out, tell the characters what to do, design the scenery and the costumes. I feel fortunate to have my own little universe.”

Sergio’s artwork in Groo may start with a “splash page” depicting a medieval village, hundreds of people in different kinds of garb, animals, wagons, tools, and weapons. All the details are painstakingly researched for accuracy in National Geographic and the cartoonist’s library of visual reference books.

Sergio also sneaks in his own feelings about issues of the day. “A comic is a great vehicle for helping: pollution, deforestation, women making less money than men, and other social problems. You realize you have a good platform for making a comment, and you use it.

“I wanted to criticize television in an issue of Groo, and it took me forever to figure out how to do it. There was no television back in barbarian days, so I finally used puppetry, a Punch and Judy show. Groo, with his violent tendencies, invents violence on television, not to mention TV dinners and commercials.”

The whole town gets hooked on puppet shows. In one scene a kid tries to get his parents to look at the beautiful sunset. Shhh! they hiss. We’re watching! “Kids love the silliness of the whole thing,” says Sergio, “but they also see how damaging television can be. I hope they ask questions of their parents.”

These days Sergio also works as a guest artist for The Simpsons comic books, writing and drawing whole issues by himself. And he’s writing a series of tales from his own life, a sort of comic-book memoir called Sergio Aragones Funnies. “I’m fortunate that I’ve met a lot of remarkable people,” he says. The stories depict his encounters with everyone from Richard Nixon to a high lama in Tibet. One story tells about meeting the famous cellist Pablo Casals in Acapulco.

Always curious, Sergio has traveled broadly and radiates the sophistication of a citizen of the world. Spanish and French were his first two languages. (His old friend Mark Evanier jokes that Sergio “does to English, his third language, what Picasso did to faces.”)

For many years he visited far-flung places such as Kenya, Paris, Hong Kong, Tahiti, and Venice with the staff of MAD. The publisher, Bill Gaines, organized a free trip every year for the magazine’s regular contributors — the cartoonists, writers, and editors listed on the masthead as “The Usual Gang of Idiots.” Once, when they traveled to Haiti, Gaines had the whole group driven directly to the house of the magazine’s one and only Haitian subscriber, where he formally presented the baffled man with a renewal card.

But Sergio’s heart belongs to Ojai. “I had always lived in a big city,” he says, “Mexico City, New York, Los Angeles. When my daughter, Christen, was very young and we came from L.A. to Ojai in 1982 for her to attend Oak Grove School, I never thought I could live here. But it took me no time to realize how comfortable, how conducive to thinking, it was. I loved it almost immediately.”

Sergio donates his time all over town, generously speaking to school kids and drawing cartoons for posters, the Ojai Library wall, and just about any group that asks. “You feel so much a part of the town,” he says. “It’s fun belonging.”

Sergio is a familiar figure around Ojai, usually dressed in shorts, his guayabera shirt untucked and pockets bulging with pens, his gray hair in a ponytail, his familiar moustache as wide as his smile. Greetings follow him down Ojai Avenue, and everyone feels they know him.

His warm feelings for the town led him to mount a retrospective exhibition of his work at the Ojai Valley Museum in 2009. “My art doesn’t really fit in a museum,” he points out. “I felt people might not understand the drawing of a cartoon, so I was always reluctant to exhibit. But Ojai is like showing my work to friends and family.”

The museum’s exhibit hall looked as if there had been an explosion in a comic book factory. An astonishing variety of Sergio’s work was on display, starting with his boyhood sketchbooks and continuing through his nearly 50 years at MAD, as well as his stint as a performer on television’s classic comedy show Laugh-In, illustrations for national advertisements, and cases displaying his hundreds of comics and books. (His recent anthology, MAD’s Greatest Artists: Sergio Aragones: Five Decades of His Finest Works, is already in its third printing.)

The cartoonist did one thing that museums definitely frown on: He drew all over the walls. “One of the basic ideas for a MAD Marginal is the corner cartoon, where the borders of the magazine connect,” he explains. “Something is coming from one way, something is coming from the other way, and you know what’s going to occur if they meet: A criminal is trying to hold somebody up on the corner, and a bunch of policemen are coming from the other corner. Your imagination fills it in.

“Well, there were a lot of corners at the museum. I could draw on a physical corner, putting a cartoon on each side, and visitors could see what was going to happen. It was perfect!”

On a narrow wall Sergio arranged three of his framed awards in a vertical line. But he hung the fourth one cockeyed and halfway down to the floor. Then he took a black marker and drew cartoon “speed lines” down the wall to show that the frame was falling. Below that, he drew a guy getting whacked on the head with a corner of the frame.

Sergio often subtly incorporates Ojai in his MAD cartoons: the Arcade, Starr Market, a kid on the street wearing an Ojai T-shirt. “Every chance I get!” he says, chortling.

If you see Sergio Aragones around town, say hello — that is, unless he’s sipping coffee and doodling on a napkin. Then you know he’s at work. “Well, it’s not really work,” he says. “Cartooning is a state of mind . . .”

(This story originally appeared in the Fall 2011 issue of The Ojai Quarterly. Republished here with permission.)

Art Town: How OSA Put Ojai On The Map

By Mark Lewis

(A somewhat shorter version of this essay originally appeared in “OSA: 3 Decades,” a book published in 2013 by the Ojai Studio Artists. Republished with permission.)

Ojai has always prided itself on being a mecca for artists. But up until 1984, the truth was far less impressive. People who came to town expecting to see artworks often were disappointed, because the works were inaccessible, hidden away in the artists’ studios. The Ojai Valley was filled with art, but for all intents and purposes it was invisible.

“It was like the best-kept secret in Southern California,” says longtime Ojai gallerist Hallie Katz, co-owner of Human Arts.

That began to change when a group of local artists banded together to launch an open-studio tour, which became an annual event. Three decades and 31 tours later, Ojai has come of age as a haven for artists and a travel destination for art lovers — and the Ojai Studio Artists have been instrumental in turning the perception into reality.

The OSA story begins in 1983, when the painter Gayel Childress took charge of the moribund Fine Arts Branch at the Ojai Art Center. The venerable building on South Montgomery Street housed California’s oldest continually operating non-profit community art center, but its dilapidated gallery space offered an uninspiring venue for art shows. At the time, there were relatively few galleries in town, and the Ojai Valley Museum did not concern itself with contemporary art. Apart from the Art Center, artists who wanted to show their work generally had only one option: The parking lot of the Security Pacific Bank (now the Bank of America), which on Sundays hosted an outdoor art market.

Childress’s first priority was to raise money to fix up the Art Center’s dowdy-looking lobby and decrepit gallery, to give local artists a better showcase. Two Arts Branch members, painters Bert Collins and Marta Nelson, had an idea. They recently had taken a tour of private homes in Los Angeles as part of a fundraising event for the L.A. Philharmonic.

“We thought, ‘Hey, what if we did that here with our studios?’ It was kind of like, ‘Hey, let’s put on a show,’ “Nelson says.

Childress, Collins and Nelson organized the first “Ojai Artist Studio Tour,” which took place on Nov. 3, 1984. Eighteen local artists opened their studios to visitors, who paid $5 to take the self-guided tour. The organizers billed it as “A Day In Art Country.”

“It was supposed to be a one-time thing,” Nelson says. “But it was so successful that we thought we’d do it again.”

The second and third annual tours were even more successful. Now known as “The Artists Of The Ojai Studio Tour,” the event attracted the attention of Sunset Magazine, which praised it for providing visitors with ready access to celebrated artists like Bert Collins, George Stuart and Beatrice Wood. (A list of other prominent artists associated with OSA at one time or another during its history would include the potters Otto and Vivika Heino and the photographer Horace Bristol.) After only three years, the studio tour was already well on its way to becoming an Ojai institution.

“It was the work of naive enthusiasm,” Childress says. “We had no idea what we were doing. But we were so passionate about it that we made it work.”

By 1986, putting on the tour had become almost a full-time job for Childress, Collins and Nelson, leaving them little time to paint. They had accomplished their initial goal, which was to refurbish the Art Center. After the third tour, they handed the event over to a local impresario, John Hazen Perry, who had big plans to take it to the next level.

Under Perry’s guidance, the 1987 tour featured an impressive, expensively produced brochure that was almost akin to an exhibit catalog.

“Everything he did was kind of epic,” recalls his daughter, Rain Perry. “That was his style.”

Perry aimed to turn the event into a full-fledged arts festival by adding music and dance. So he produced a multimedia extravaganza at Matilija Auditorium to coincide with the tour. Thirty-five artists opened their studios to the public that year, but Perry’s new features cost a lot more than they brought in, and the tour lost money.

“The vision was beautiful and breathtaking,” Rain Perry says, “but his ability to stay within a budget was not.”

Exit Perry, after only one year at the helm.

The tour then passed to Ojai Events Ltd., which consisted of several local business owners (including Les Gardner of the Attitude Adjustment Shoppe) who tried to operate the tour for a profit. But this group had little experience managing artists.

“We were out of our element,” Gardner says. “And it was a very difficult group to work with.”

In what turned out to be a controversial move, the new producers brought in an outside art expert to jury the tour and thus raise its artistic standards. Unsurprisingly, this created ill will among those artists who did not make the cut. Things did not go smoothly for Ojai Events Ltd., and in 1988 the tour lost money for a second consecutive year.

Meanwhile, some of the artists were beginning to take matters into their own hands. One day in 1988, the printmaker Linda Taylor and the potter Vivika Heino were lamenting the tour’s decline, and wondering how it could be restored to its original purpose: to showcase art and benefit the community.

“We could do this ourselves,” Heino told Taylor.

That conversation planted the seed. About 20 artists, including the tour’s three co-founders, convened on the back deck of Taylor’s Drown Street home to form a new artists’ cooperative. They decided to adopt standards for membership, to ensure that everyone in the group would be a professional artist whose work had been recognized for its quality. And they decided that they would operate the group on a nonprofit basis, using the proceeds to support the arts in Ojai.

At this point, Ojai Events Ltd.was still operating the annual studio tour. But Gardner and his partners bowed out after the 1989 event. “It became a lot more hassle than it was worth,” he says.

But the fledgling artists’ cooperative was not yet in a position to take over the tour. So in 1990 there was only an informal mini-tour, featuring four artists with studios in the East End or the Upper Valley — Gayel Childress, Audrey Saunders, Nancy Whitman and Beatrice Wood. Meanwhile the artists’ cooperative struck an alliance with the Ojai Valley Chamber of Commerce, which agreed to act as the tour’s financial receiver in return for a cut of the proceeds. And so the event was reborn in 1991 as the Ojai Studio Artists Tour – the 11th annual tour but the first under the OSA name, which it has proudly carried ever since.

In 1993, OSA began awarding scholarships to promising local students to help them further their arts education. (By 2013, the total amount awarded would reach surpass $100,000.) The group also began its outreach program, under which OSA members welcome budding artists into their studios for instruction and inspiration. Other regular beneficiaries of OSA’s largesse include the Ojai Library, which has reaped a bounty of donated art books over the years; and the Art Center, which continues to benefit from its historic connection with the art tour. (OSA also organizes a group show in the Art Center gallery each October in conjunction with the tour, and mounts another group show each spring at the Ojai Valley Museum.)

“We don’t do the tour just to show our artwork and to have people come; it’s because we have a purpose,” Bert Collins says. “We’re doing it to raise money to support arts in the community.”

Khaled Al-Awar, who owns Ojai’s Primavera Gallery, credits the OSA tour with boosting the community’s reputation as a destination for art lovers.

“People love to say that they’ve met the artist,” he said. “It personalizes the art.”

In 1994, OSA acquired a copycat competitor, the Ojai Art Detour, which holds its own studio tour each October on the same weekend. (Unlike OSA, whose members must be voted in, the Detour is open to any artist who lives in the valley and wants to participate.)

In 2006, OSA acquired its 501(c) 3 designation as a non-profit organization, severed its connection with the Chamber of Commerce, and began operating the tour entirely on its own. The Great Recession that began in 2008 posed a daunting challenge, yet OSA has endured. Each year, more than 50 members open their studios to visitors as part of the annual tour. Taking the Detour participants into account, more than 100 art studios in the Ojai Valley typically are open to the public each year during the second weekend in October, reflecting the enormous growth of Ojai as an arts mecca since the original 1984 tour first put the town on the map.

The OSA story reveals how a group of talented, temperamental artists have managed to work together to create an enduring legacy: Ojai as a special place where school-age artists are nurtured, emerging artists are supported, and mature artists are celebrated.

“We established Ojai as an art town,” Linda Taylor says. “It’s been a lot of work, but we showed the community that Ojai is an art town.”

Â

The Mason Chronicles (1)

Ojai Was The “Journey’s End” For The Gorham Family

By David Mason

“Plans are completed and the contract let to A. Pefley for the construction of a unique and attractive foothills residence. H.M. Gorham, a banker of Santa Monica, will occupy the new villa, to be constructed entirely of cobble stones and moss-be-whiskered rocks, with tile and slate roof.”

-The Ojai, April 21, 1916

In a large formation of rocks piled high overlooking the East End of the Ojai Valley lies a silent giant.

Emerging from the earth and dominating the serene landscaping is a life-size stone whale. Its features are so detailed that it is hard to imagine that it is a sculpture done by Mother Nature during one of her more playful moods.

The area is a shady retreat with a freshwater stream that runs nearby. The early Indian population of this valley must have felt the reverence that prevailed in this area, for they would spend much time in the shadow of this great wonder.

Harry M. Gorham also must have felt the serenity when he first arrived in the Ojai. He was a man who could very well have afforded any other location in the world to build his home, but he chose the Ojai Valley.

Gorham was born in Cleveland, Ojai in 1859. He attended school there and was preparing to attend Harvard, but his plan did not materialize. Gorham’s uncle, John P. Jones, was a U.S. senator from Nevada, and he persuaded young Gorham to go to Virginia City to take a job in the Comstock silver mines, which Jones owned. The year was 1877.

The Comstock Lode would hold Gorham’s interest for 26 years, during which time he progressed up the ladder of success to superintendent of mines. He assumed a great deal of company responsibility because of the absence of his uncle, who was busy with the senatorial affairs and his vast real estate holdings in Santa Monica, Calif.

After a brief illness, Gorham left the mines and went to Southern California to join his uncle in his business ventures there. Gorham eventually became president of the Bank of Santa Monica.

Senator Jones’ daughter Marian developed great skills in tennis, winning the National Women’s Championship for two years. Gorham’s son Hal shared his cousin’s interest in the sport and in 1905 they both came to Ojai to compete in the interscholastic singles division of the Ojai Tennis Tournament. Harry Gorham, a widower, always attended the matches in which his son participated, and he became interested in the Ojai Valley during the tournament here.

Gorham met Mrs. Florence Rogers during one of his trips to the Ojai Valley. She was born in Cairo, Ill., and as a young lady, she had also been very active in the game of tennis. She attended Vassar at the age of 12 and achieved an outstanding scholastic record. She had met her first husband, Emery Rogers, a Harvard man, in Chicago, and after they were married they lived in Boston. Two children were born to them, a boy named Emery and a girl named Constance and called Connie. They were a very happy and proper family until Mr. Rogers died at a very young age of tuberculosis.

After the loss of her husband, Mrs. Rogers took an extensive trip to Europe. Her thoughts were that they would live in a different country each year and perhaps never come home.

As the children grew older, Mrs. Rogers became concerned that her son was falling under corruptive influences. She had this notion that he was going to get himself a mistress and steal off to live “la vie boheme” in some Paris garret. So she set about hunting down a stern, rigorous prep school to pack him off to.

Rogers cabled her mother and asked her to check into a school she had heard about that was in the small town of Nordhoff (now Ojai), called The Thacher School. After receiving the word back that the school was held in high regard, the Rogers family left Europe in 1907 on the first boat home.

Arriving in the Ojai Valley, the family found a small village with a post office and a few stories clustered together. The houses were scattered about the sagebrush-covered valley.

The family stayed at the Pierpont Cottages while waiting to get young Emery into Thacher. The school had a waiting list, but Mrs. Rogers was determined that her son would go there.

Since most of the people of the valley depended upon horses for transportation, she ordered an elaborate cart from Ireland for the family to use.

Shortly after she settled in the valley, she met Harry Gorham and they fell madly in love. They married a short time after their first meeting.

In 1908, the newlyweds built Casa de Paz on McAndrew Road, but when young Emery finished his schooling at Thacher, the Gorhams sold the house and moved to Santa Monica.

By 1916, with the purchase of the Whale Rock Ranch in the Ojai Valley, the Gorhams had decided to build a small stone cottage for a weekend retreat. They named it Journey’s End.

The house was built entirely of rock, hand-selected from the property. When finished, it commanded a view of the entire valley. It had one large room, with a fireplace that doubled as a source of heat and a means of cooking.

The beams for the house were put into place with the use of donkeys and ropes, under the supervision of Mrs. Gorham.

The extensive use of tile manufactured by the Gladding McBean Co. added color and character to the strong appearance of the stone. To quote the front-page headline of The Ojai: “New Modern Home to Beautify Valley.” That, indeed, was a true statement.

Young Emery Rogers joined the Army during World War I, and from his description of Major Carlyle H. Wash, his commanding officer, Mrs. Gorham decided that since the major was also a graduate of West Point, he might be the perfect gentleman for her daughter Connie. They were married in 1919.

The newlyweds moved with the military from base to base until 1921, when Wash was assigned as air attache to the American embassy in Paris, where they lived for three years. Carlyle Wash would continue his success in the Army, eventually becoming a general.

In 1932, when Mr. and Mrs. Gorham left Santa Monica to live at Journey’s End permanently, they added a small kitchen, bath and bedroom.

During World War II, General Wash was killed, along with his staff, in a plane crash during a storm. Connie and her young daughter Patsy returned to the Ojai Valley and to Journey’s End.

A second home was built on the property for Connie in 1948 by Ojai designer Austen Pierpont. It was built on the hillside with a balcony. The single-story home had a red tile roof and a sweeping view of the valley.

Connie Wash became quite active in events that were taking place in and around the valley. During the war, she was the tri-counties chairwoman of the Camp and Hospital Committee of the American Red Cross. She was also a hardworking member of the Ojai Chamber of Commerce and the East Ojai Valley Association. She spearheaded the movement to replace the street signs with the wooden signs that we now enjoy.

The Ojai Garden Club elected her president, and she helped to get the other members more involved in the city. She was a strong supporter of the Ojai Music Festival.

In 1969, another wing was added to the original Gorham house to make it larger. Through it all, the house retained its charm.

Today, the beautiful Journey’s End is an estate that has withstood all the elements, having been featured on the television show “20/20″ with the 1985 fire sweeping around it. The home has continued to be protected and loved by the same family.

In 1986, the county’s Cultural Heritage Board declared this property Ventura County Landmark No. 103, with the hope and desire that the Whale Rock and the romantic Journey’s End will remain for many future generations to come and enjoy.

As for the large whale, it still looms over the countryside and is now shaded by the many live oaks that cover the area. To all of the Ojai Valley, it remains a place held in high regard, deep respect, love and awe.

The above column originally appeared in the Ojai Valley News on Dec. 3, 1999. Republished with permission.

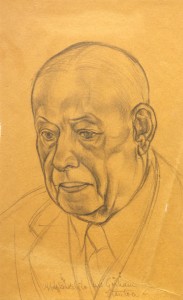

Focus on Photography: Going Behind the Portraits

In conjunction with the museum’s current exhibit, “Fine Portraits, Fine People,” we present Anca Colbert’s recent Ojai Quarterly essay on the art of photographic portraits, which focuses on Ojai’s own Guy Webster.

A portrait! What could be more simple and more complex, more obvious and more profound.

– Charles Baudelaire, 1859

By Anca Colbert

The celebrated Paris Photo Show came to Los Angeles for the second year last April. The event, held at Paramount Studios in the heart of Hollywood, attracted the interest of the press, celebrities and a public eager to look, get informed and collect new artworks. “Portraits of Our Time,” a monumental limited-edition book of Annie Leibovitz’s work just released by Taschen Books, was drawing crowds and creating a sensation at their booth.On the heels of the two previous fairs held in January, the Photo L.A. show and the Classic Photo show, the huge success of this international event confirms the strength of the photographic art market, and the growing importance of Los Angeles as a city that supports this young and popular art form.

In the Spring 2014 Issue of the Ojai Quarterly we considered the accelerated evolution of photography as a technique and as an art, and the difference between a snapshot and a photograph. We continue our series on photography by taking a closer look at photographic portraits.

Painted portraits were part of art culture for centuries. To this day, Da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” remains the most celebrated and mysterious of all paintings. But ever since the birth of photography around 1850, portraits in the most accessible and democratic of all art forms have captivated a wider audience, always hungry for more images, and in recent times with an ever-increasing appetite for personalities. From Nadar and Stieglitz to Gertrude Kasebier, Man Ray, August Sander, Cartier-Bresson, Henri Lartigue, Brassai, Diane Arbus, Mapplethorpe, Cindy Sherman, Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, we all have our favorites.

So, what’s the fascination with portraits? And what exactly are they? Are portraits able to capture the psychological character of the sitter? How “personal” is that image of a person? Portraiture is commonly regarded as a window into the soul of the sitter. But is it? Could it be a window into the soul of the photographer?

Photographic portraits, which fast surpassed the popularity of traditional painted portraits once the technology was available, are perceived as a way to capture reality. But how much do they, really? Whether in studio settings or in photojournalism circumstances, a psychological layer adds a twist to the situation, as Richard Avedon plainly put it: “A photographic portrait is a picture of someone who knows he is being photographed.” As we look at a portrait, we look at the dynamic interaction between an artist and a sitter, and at the energy in that space between them.

Photographic portraits are an interpretation of the reality of the person being photographed, as imagined by the photographer, and as perceived by the viewer. It’s all illusion, played by a trio.

Ojai is famous for being home to artists and creatives. Among the distinguished photographers who have lived and worked here are Horace Bristol (renowned for his photos of Dust Bowl migrants), and more recently Cindy Pitou Burton, Donna Granata and Guy Webster.

Guy Webster moved to Ojai 34 years ago. While he still commutes to his studio in Venice for weekly shoots of celebrities, he loves his family life in this heavenly valley, where he rides one of his many motorcycles every day. Guy loves speed, and motorcycles are his lifelong passion.

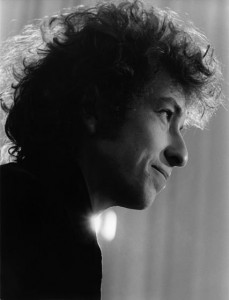

One of the early innovators of rock ‘n’ roll photography, Guy started by shooting album covers and billboards in the 1960s for groups that included the Rolling Stones, the Mamas and the Papas and the Beach Boys among numerous others.

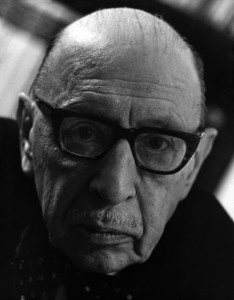

As the primary celebrity photographer for hundreds of worldwide magazines, Webster has captured a vast range of talent in the world of music and film, from Igor Stravinsky to Truman Capote, Alan Ginsberg, Zubin Mehta, Alan Watts, Sean Connery, Mick Jagger, Jack Nicholson and Michelle Pfeiffer to his longtime Ojai friends Malcolm McDowell, Mary Steenburgen and Ted Danson.

Born and raised in Beverly Hills, Guy became a photographer by accident. It was 1961; he had just graduated from Yale and gotten into the Army. While stationed in Carmel, he volunteered to be a photography instructor without knowing anything about photography. He spent the night reading up on the subject, and the next day started teaching it! Later, back in Los Angeles, he had connections with some rock ‘n’ roll groups and record companies. The photograph that made him famous was the 1965 record cover of the album California Dreamin’ for The Mamas and The Papas: he shot them in a bathtub. After that, Guy says everybody in Hollywood wanted him to photograph them; it was the beginning of his stellar 50-year career.

The essence of photography is light and shadow. Guy Webster’s portraits speak that language fluently. I brought up my keen interest in the light quality of his portraits, particularly in his black and white work; he was pleased to tell me about his love for Italian painters, Caravaggio in particular. Caravaggio’s illumination of his subjects, known as Tenebrism, is a technique similar to chiaroscuro by which strong contrasts of light and dark are used to add emotion and drama to an image as if seen through a spotlight effect or illuminated by a candle. Other Baroque painters used that technique with memorable results, notably Rembrandt, Rubens, La Tour and Vermeer.

Guy Webster’s portrait of his friend John Nava offers an interesting reflection: double take on the painter living in Ojai, world renowned for his portrait work. Webster catptured the interplay of light and shadow in his old farm house in Spain, every subtle transition in the fabric of the shirt and on the wood of the chair, and the profile of the painter gazing intensely at what we cannot see.

In his early portraits of Barbara Streisand and Bob Dylan, it’s interesting to note the light glowing around their throat area, a subtle indication of their golden voices.

Columbia Records sent Guy on an assignment to photograph Igor Stravinsky at his home: he captured the composer, whom he immensely admired, in a very close-up frontal shot and at an angle focusing the light on the composer’s large forehead, clearly intending to give a hint of his genius.

A savvy storyteller, Guy exudes intelligence and calm. There is kindness, even sweetness, to his portrait work with celebrities — no doubt a reflection of his own temperament projected onto his sitters.

“A portrait is not a likeness. The moment an emotion or fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.”

— Richard Avedon

The Peter Fetterman Gallery in Santa Monica has been one of the finest galleries to exhibit classic and modern photography in the Los Angeles area since opening their space at Bergamot Station twenty years ago. Fetterman has a penchant for portrait photography, and his recent show “Portraits of the 20th Century” focused precisely on this theme. I asked Peter to share some thoughts about one portrait in the show that particularly moved me, the one of Martin Luther King Jr. by Dan Budnik:

“I have always had a great personal interest in civil rights photography. In my research for images for MLK for a civil rights exhibition, I came across this one. It was 1994. I had never heard of the photographer. He had fallen through the cracks. I found him, met him and discovered an untapped great archive. This is the greatest King portrait ever, taken moments after he had finished his greatest speech, ‘I have a Dream.’ Tears come to my eyes as I write this now, so many years later.”

In my book of art life, to be moved to tears by an image is always a good sign. Art has that power to touch us deeply. As the fascination with portraits retains its appeal with art lovers and remains an essential form of expression for professional photographers, photography continues its irresistible ascension as the visual art form of our times.

Anca Colbert is an Ojai-based art consultant and curator; the editor and publisher of Arts About Town, a guide to the arts life and activities in Ojai; and the arts columnist for the Ojai Quarterly. This column first appeared in the Quarterly’s Summer 2014 issue. Republished with permission.

Gene Lees in Ojai: Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars

By Mark Lewis

Ojai prides itself on its small-town charm, but it is not so small that everyone actually knows everyone. A person can live here for three decades — as Gene Lees did — without being widely recognized. So when Lees died in April 2010 at the age of 82, his friends mourned, and his Foothill Road neighbors took note, but his passing was not big news in his adopted hometown. The Ojai Valley News did not run an obituary.

Elsewhere, it was a different story. The New York Times hailed Lees as “a prolific jazz critic and historian who approached his subject with a journalist’s vigor and an insider’s understanding.” The Washington Post eulogized him as “a multi-talented writer who left a lasting mark on jazz as a biographer, an opinionated critic, and graceful song lyricist.” The Los Angeles Times quoted former New Yorker Editor Robert Gottlieb, who described Lees as “a strong presence in jazz.”

All the obituaries dutifully reported that Lees had died “in Ojai, Calif.” None explained how it was that a legendary jazz writer had ended up in this bucolic valley, so far from the big-city clubs where his favorite musicians plied their trade. A hint can be found in Lees’s most famous lyric, even though he wrote it years before he first set eyes on Ojai.

EUGENE Frederick John Lees was born in Hamilton, Ontario, on February 8, 1928. As a young man he dreamed of becoming a painter. Instead he went into journalism, first in Canada and later in Kentucky, where he served as a music critic for the Louisville Times. By 1959 he was in Chicago, editing the jazz magazine Down Beat.

After leaving Down Beat in 1961, Lees volunteered to tag along with the Paul Winter Sextet on a State Department-sponsored tour of South America. Lees was intrigued by what he had heard of bossa nova music, and he wanted to trace it to its source. When the tour reached Rio de Janeiro, he contacted the songwriter Antonio Carlos Jobim, and they quickly became friends. On the bus trip from Rio to the tour’s next stop, Lees jotted down some English-language lyrics for Jobim’s “Corcovado.” (The original lyrics, of course, are in Portuguese.) This is how the Lees version begins:

Quiet nights of quiet stars

Quiet chords from my guitar

Floating on the silence that surrounds us

Quiet thoughts and quiet dreams

Quiet walks by quiet streams

And a window looking on the mountains and the sea, how lovely

When the tour ended, Lees headed for New York City. He had written a novel, which he hoped to sell to a publisher, and he also had aspirations as a lyricist.

“That first year in New York was one of the most difficult of my life,” he recalled in his book Friends Along the Way: A Journey Through Jazz. “I couldn’t, as they say, get arrested. I couldn’t sell my prose, I couldn’t sell my songs. At any given moment I was ready to quit, scale back my dreams to the size of the apparent opportunities, leave New York and find some anonymous job somewhere.”

Then things started to click.

“I was the pianist on the first recording of one of his songs,” recalls the composer Roger Kellaway, a longtime Ojai resident. “The song was called ‘Fly Away My Sadness,’ and the vocalist was Mark Murphy.”

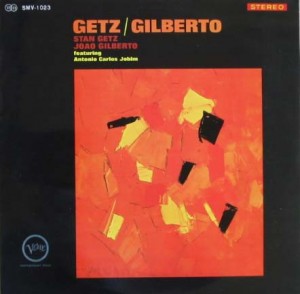

A few months later, Tony Bennett recorded “Quiet Nights (Corcovado)” for his hit 1963 album I Wanna Be Around. Then came Getz/Gilberto, an epic event in jazz history. Released in March 1964, this album by Stan Getz and Joao Gilberto transformed the bossa nova craze into an international phenomenon. The hit single was “The Girl From Ipanema,” for which Lees did not supply the lyrics. But he did write the album’s liner notes, and the LP also featured Astrud Gilberto singing Lees’s version of “Corcovado.” (The English version eventually would become better known as “Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars.”)

Lees had made a successful transition from journalist to songwriter. His lyrics for his friend Bill Evans’s tune “Waltz for Debby” became another standard. But there was a cloud on the horizon, because 1964 was also the year of Meet the Beatles. Rock ‘n’ roll was the coming thing, and sophisticated jazz-pop songs — the kind Lees wrote — would soon be on their way out.

“Oh my God, he hated the Beatles,” recalls his widow, Janet Lees, chuckling at the memory of Gene’s bitter fulminations against rock music.

The next few years constituted a kind of Indian summer for jazz singers, who continued to score occasional Top 40 hits. Lees had the privilege of watching Frank Sinatra record “Quiet Nights” for the classic 1967 album Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim. Lees also supplied the lyrics to “Yesterday I Heard the Rain” for Tony Bennett, and he translated “Venice Blue” for Charles Aznavour.

“Venice Blue” also was recorded by the rocker-turned-crooner Bobby Darin, whom Lees considered a talented singer. This association with Darin “was probably about as close to the pop industry as he ever got,” Kellaway said of Lees, his old friend and frequent collaborator.

Kellaway himself was more adaptable; he went on to work with the likes of George Harrison. But Lees could not accommodate himself to the new order.

“Had Gene been born sooner, he would surely have been as famous and successful as the top songwriters of the ’30s and ’40s,” the Wall Street Journal critic Terry Teachout wrote after Lees’s death. “But he came along after the cultural tide of jazz had started to ebb … Not surprisingly, he despised rock, which he believed had laid waste to the lost musical world of his youth.”

As he turned 40 in 1968, Lees faced diminishing prospects as a songwriter. His personal life was also unsettled after two failed marriages (one of which had produced a son). Then Lees met Janet Suttle. By 1971 she was Janet Lees, and they were living in Toronto, where Gene ran Kanata Records. (Among the albums he put out during this period was his own Bridges: Gene Lees Sings the Gene Lees Songbook.)

As he turned 40 in 1968, Lees faced diminishing prospects as a songwriter. His personal life was also unsettled after two failed marriages (one of which had produced a son). Then Lees met Janet Suttle. By 1971 she was Janet Lees, and they were living in Toronto, where Gene ran Kanata Records. (Among the albums he put out during this period was his own Bridges: Gene Lees Sings the Gene Lees Songbook.)

Things were looking up on the songwriting front, too. The legendary director Joshua Logan was developing a new Broadway musical called Jonathan Wilde. Composer Lalo Schifrin, already famous for his Mission: Impossible theme, was writing the music. Logan brought Gene in as the lyricist. “Logan told Richard Rodgers, ‘I’ve found the next Hammerstein,’ ” Janet Lees recalls.

The job required Gene to make frequent trips to Southern California, where Schifrin was based. Eventually, Gene and Janet made a permanent move from Toronto to Tarzana, where they bought a house. To their great disappointment, Jonathan Wilde was never produced, due to a legal dispute between Logan and the show’s original writers. But Gene kept busy with other projects, such as collaborating with Roger Kellaway on the songs for an animated film, The Mouse and His Child. There was still a market in Hollywood for the sort of lyrics he wrote, even though rock music and disco now completely ruled the Top 40.

But Lees’s career was about to enter an entirely new phase. And the turning point can be traced to a weekend trip he and Janet made to Ojai.

LEES already knew Ojai fairly well. “He used to come up here and work with Lalo Schifrin, who had a house behind the Presbyterian Church,” Janet said. But on one particular weekend, sometime in the late ’70s, something special happened. The clock-radio alarm in their motel room was tuned to the only station in town: KOVA-FM, owned by jazz expert Fred Hall. On Sunday morning, Gene awoke to sounds he did not readily associate with small-town living.

“I heard first Count Basie, then Jack Jones, and a man who discussed them with great knowledge,” Lees later wrote. “This brought me to full wakefulness, and when I heard the station’s call letters, I telephoned and spoke to him. That’s how I met Fred. He invited me to visit the station, which I did later that morning.”

Ojai in those days was something of a jazz hotbed. The famous trumpet player Maynard Ferguson lived here. The annual Ojai Music Festival always included a jazz component, organized by Fred Hall and Lynford Stewart. Later on in the ’80s, Wheeler Hot Springs began to host performances by the likes of Ray Brown, Mose Allison, Charlie Byrd and the Manhattan Transfer. At the heart of it all was Hall, whose radio show “Swing Thing” reached a national audience via syndication. Gene and Janet immediately hit it off with Fred and his wife, Gita. The Leeses also fell in love with Ojai, a place where quiet nights of quiet stars are almost a nightly occurrence. At some point, Gita asked the obvious question: “Why can’t you live here?”

The answer, essentially, was “No reason at all.” The Leeses left Tarzana behind and rented a house on Signal Road. Later they moved into an apartment complex in the Mira Monte neighborhood, before eventually settling in house high up on Foothill Road. Gene, Fred and Lyn Stewart teamed up to produce the “Jazz At Ojai” concerts in Libbey Bowl. And Gene turned from writing jazz lyrics to writing jazz essays.

The catalyst was the 1981 death of his friend Hugo Friedhofer, the distinguished film composer. To Gene’s immense frustration, he could not persuade the New York Times to run an obituary. The giants of his era were passing, and nobody seemed to be noticing. It was time for Lees to return to his roots as a journalist, to memorialize their achievements.

“That’s when Gene started the Jazzletter,” Janet said.

Lees put out his newsletter from 1981 until he died. It featured eloquent essays on a wide range of topics, not all of them jazz-related, but all of them beautifully written and brimming with passion. It became an institution in the jazz world, cherished by its subscribers.

“The Jazzletter was wonderful,” Kellaway said. “There were long, long dissertations on whatever he chose as a subject.”

He filled the Jazzletter with biographical essays, many of which were collected into books. He also wrote full-length biographies of Oscar Peterson, Woody Herman and Johnny Mercer. (At his death, Lees was putting the finishing touches on a life of Artie Shaw, which may yet be published.) Long or short, most of these profiles featured Lees himself in a supporting role, since he was always part of the story.

“Gene actually knew personally everybody that he wrote about,” Kellaway said. “He knew Basie and Tommy Dorsey. He knew everybody.”

At first, Lees continued to work as a lyricist while putting out the newsletter. In the early ’80s he acquired an unlikely collaborator: Pope John Paul II, who as a young priest had been given to writing poetry. Two Italian composers had set these poems to music, and Lees was hired to translate them into English lyrics. The result was a song cycle that was performed in a special concert in Germany, with vocals by Sarah Vaughan. The concert was recorded, but no major record company was interested, so Gene and Janet put the record out themselves with the title The Planet is Alive … Let it Live!

After that experience, Lees focused more on prose than poetry. His readers — and his friends — were seldom in doubt about where he stood. He liked to drink and he liked to argue, and the combination was not always pleasant for the people around him. Nevertheless, the jazz critic Doug Ramsey enjoyed jousting with Lees.

“He had strong opinions about everything,” Ramsey wrote in his Lees obituary. “We argued. Arguing was half the fun of knowing Lees. Every argument with Gene was a win for me because I had learned from him.”

Lees suffered from ill health during his final years, but he kept on writing — and not just about jazz legends from the past. One younger singer he admired was Diana Krall, who returned the compliment by recording his best-known lyric as the title song of her most recent album, Quiet Nights.

During Gene’s three decades in Ojai, the town lost some of its jazz chops. Fred and Gita Hall sold the radio station and later moved away. Wheeler Hot Springs closed, and the Ojai Festival stopped featuring traditional jazz. But Ojai remained well known in the jazz world as the home of Gene Lees and the Jazzletter. (Gene and Janet also deserve credit for bringing the violin virtuoso Yue Deng to live in Ojai, after they took her under their wing and introduced her to jazz.)

When Gene died on April 22, 2010, Janet was stunned by the outpouring of tributes from jazz writers and musicians across the globe. Eulogies were printed as far away as London, where the Times called Gene “one of the most dazzling lyricists in popular songwriting, and the Boswell to a generation of jazz musicians.”

“I just didn’t think of him as being so well-known all over the world,” Janet said.

In Ojai, not so much. Yet it was here that the man who wrote “Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars” finally found his own Corcovado, after first finding the person to share it with. Here’s how the song ends:

This is where I want to be

Here with you, so close to me

Until the final flicker of life’s ember

I who was lost and lonely

Believing life was only

A bitter tragic joke, have found with you

The meaning of existence, oh my love

This article originally appeared in the winter 2011 issue of the Ojai Quarterly. Republished here with permission. Janet Lees died in 2013. Gene Lees’s Artie Shaw biography has not been published. (Posted by Mark Lewis, December 2014)

Jailhouse Rocked

The Ojai murder case that put Johnny Cash behind bars at Folsom Prison

By Mark Lewis

Ojai is not renowned for famous murders. But there was one local case, involving an accused murderer named Earl Green, that deserves at least a footnote in the history books, because it set off an unlikely chain of events which eventually led to the making of Johnny Cash’s legendary “At Folsom Prison” live album.

Cash never did any hard time in his life, but Green did – in Folsom Prison, no less. And Cash never actually shot a man in Reno “just to watch him die” – but Green crushed a man’s skull with a baseball bat near Ojai, just for $9 and a wristwatch. That at least was the DA’s version of events; Green claimed he acted in self-defense. The jury bought the DA’s version and sent Earl to death row. But he ultimately evaded the gas chamber and ended up in Folsom, serving a life sentence. As a result, years later, Green was able to play a key role in bringing Cash there to perform. In fact, if Green had never picked up that baseball bat, Cash’s Folsom concert might never have happened.

The story begins on Labor Day 1954, when Earl Compton Green Jr. and his friend Joseph Oliver LaChance drove from Pasadena to Ojai to apply for work at a local resort.

Green, 27, was an ex-Marine and a convicted felon from Florida, who recently had moved to Pasadena with his second wife and her 3-year-old daughter by an earlier marriage. He found work as a kitchen helper at the Annandale Golf Club under an assumed name. There he met LaChance, 49, an ex-con from Canada who worked at Annandale as a guard.

Green already was itching to move on from Pasadena. He was afraid that his mother-in-law, who resided there, would report him to the Florida authorities for breaking the terms of his parole by leaving the state. (He had served three years for armed robbery. Apparently the mother-in-law did not consider him a suitable match for her daughter.) LaChance had an idea: Why not move to out-of-the-way Ojai, where no one would know who he was?

LaChance apparently had worked at an Ojai resort in the past (probably Matilija Hot Springs), and he offered to use his contacts there to find jobs for both Green and himself. On Labor Day they drove in LaChance’s car to Ojai, stopping several times along the way to have a few beers. When they arrived at the resort, they were told that the man they wanted to see would be away from his office for two hours. So they had a few more beers and drove out to Matilija Lake to kill some time while they waited.

The police theory of what happened next is that Green saw an opportunity to rob LaChance, so he bashed him twice on the back of his head with a bat when the older man stooped down to get a drink of water. Green’s version is that they had driven up there to do some target shooting, but instead LaChance made an aggressive pass at him.

“We got there and he didn’t want to shoot gun, he wanted to play around,” Green told Johnny Cash biographer Michael Streissguth many years later. “And so I hit him with a bat I picked up, and I hit him too hard and I killed him.”

(Streissguth, who filmed a lengthy interview with Green in 2007 for a documentary film about Cash, has graciously shared the interview transcript with the Ojai Quarterly.)

Green took LaChance’s wristwatch and the $9 he found in the man’s pockets, and drove off in LaChance’s 1951 Chevy sedan. He stopped in Pasadena just long enough to pick up his wife and her young daughter, then set off on a cross-country crime spree. He pawned the watch; sold the car somewhere in Ohio; robbed a supermarket in Richmond, Ind.; then committed another robbery in Ocala, Fla. Then he headed west again, moving from town to town, keeping one step ahead of the law. The police finally caught up to him in March 1955 by setting up a roadblock on Route 66.

“They run me down in Amarillo, Texas,” he told Streissguth. “They knew what kind of car I was driving and that’s how they got me.”

In the car they found Green, his wife and stepdaughter and an 18-year-old male accomplice, along with a .22 rifle and a sawed-off shotgun. Green put up no resistance. He had gotten away with $6,000 in cash from that Indiana supermarket robbery, but had less than 75 cents on him when he was arrested.

Three months later, on trial for his life in a Ventura County courtroom, Green admitted killing LaChance, but claimed temporary insanity. Being propositioned by a man, he said, had prompted a violent reaction, essentially in self-defense. The jurors didn’t buy it; they convicted him of first-degree murder and sentenced him to death.

All capital murder cases automatically were appealed, but Green had little reason to think that his conviction might be overturned. He spent the next 16 months on death row in San Quentin, waiting for his date with the gas chamber down in the prison basement.

“I thought, ‘This is it, man,'” Green recalled. “I’ve seen three men go down. They shook my hand and then they took them down the day before [their execution].”

But Green would never take that fatal trip to the basement. In October 1956, the California Supreme Court affirmed his murder conviction but overturned his death sentence, on the grounds that the trial judge had erred in his instructions to the jury. Reversing an 82-year-old precedent, the court stunned the state’s legal community by ordering a new trial to determine Green’s punishment.

Improbably, Green had a new lease on life. But Ventura County District Attorney Roy Gustafson still wanted his scalp, and Green had every reason to fear that the next jury, properly instructed, would send him right back to death row. So he developed a new strategy. He acted so bizarrely that he was declared incompetent to stand trial. This is not easy to do – if it were, then every capital-murder defendant would try it. But Earl Green pulled it off. “Green broke down and was declared hopelessly insane,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

He was sent to the Atascadero State Mental Hospital, where doctors eventually determined that he was fit to stand trial. Unwilling to face another jury, he escaped from Atascadero, but was soon recaptured. Hauled up before a judge in yet another Ventura County courtroom, he once again went into his crazy act. And once again it worked, earning him a return ticket to Atascadero. Then he surprised everyone by admitting that he had been faking insanity all along to avoid the gas chamber. “Green told Gustafson he was sorry he had caused so much trouble and was especially sorry about pretending to be God,” the Times reported.

So, back to death row? Not this time. Green had worn down Ventura County justice officials with all his antics, and they had little desire to put him on trial again. After a brief hearing in February 1958, a judge gave him a life sentence, and at the age of 30 he was sent to live out the rest of his days in Folsom Prison.

“Well, you know Folsom was for hardened criminals,” Green told Streissguth. “Those that were there were on the end of the line. No looking for parole or anything; you run out your life in prison. And it was a prison within a prison. It had them big old six-foot [thick] walls. And then you went through them and went down through the inner part, and there was another wall! And that was the inner prison, I was told.”

Green found Folsom more congenial than San Quentin in at least two respects: It had no gas chamber, and it was not dominated by inmate gangs. A man could “do his own time” at Folsom, meaning that if he minded his business and kept his nose clean, he could stay out of trouble with the guards and with his fellow inmates: “If you won’t bother them, they won’t bother you.”

Green steeled himself for the likelihood that he would pass three or four or even five decades behind those walls. His wife had borne him a son conceived before his arrest, but Earl told her to get a divorce, take the child and forget all about him. She took his advice; apparently he never saw her or the boy again. Nor did he maintain contact with his older son from an earlier marriage. He drew a curtain on the past, and settled in to do his time.

Green found solace by returning to his Christian roots. Raised as a churchgoer, he had fallen away from grace during his hell-raising years. But after his arrest, he had struck up a friendship with the Rev. Floyd Gressett, a Ventura pastor who ministered to county jail inmates. Gressett had visited Green on death row in San Quentin, and continued the visits after Earl landed in Folsom as a lifer.

Green also spent a lot of time in Folsom’s Greystone Chapel, which served both Protestants and Catholics. “I went there for my benefit to get spiritual uplifting,” he said.

To help the time pass more quickly, Green kept busy by playing country music with friends.

“I took up the bass guitar while I was in there,” he said. “I had my mother send me one, an electric guitar. And I learned the bass and I had me a little band. … And it was something that I did on my own to [keep from] going insane. I bet if you sat there watching walls all day you would go insane.”

One day he noticed a new inmate playing a guitar by himself in the prison yard. This was Glen Sherley, who was doing time for armed robbery. Glen was a decade younger than Earl, but the two men had similar musical tastes, and they hit it off. “So we got together and played, and he played me a lot of his songs,” Green recalled. Impressed with their quality, Green urged Sherley to try and sell them to a music publisher. Glen shrugged off the suggestion. “He thought nobody would do nothing with them songs,” Earl recalled. “He didn’t think nobody would do anything for him.”

The years passed and Green thrived in prison, to the extent possible. By 1964, he was serving as the in-house DJ, “the Voice of Folsom Prison,” spinning songs that inmates could listen to on headphones in their cells. Green was big Johnny Cash fan, and he knew that Johnny had performed several times for the inmates at San Quentin. (A young Merle Haggard attended at least one of those shows while serving time for burglary.) If Cash could play San Quentin, why not Folsom?

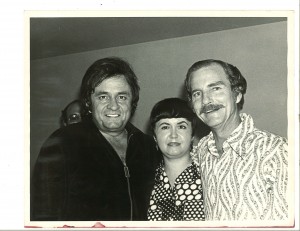

Green knew from Floyd Gressett that Cash was now living in the Ojai Valley, and sometimes attended services at Gressett’s nondenominational Avenue Community Church in Ventura. As Gressett later related the story to Ventura Star-Free Press reporter Gene Beley, it was Earl Green who now kicked off the chain of events that eventually brought Johnny Cash to Folsom Prison.

“One time when I visited Green,” Gressett said, “he asked me what the possibility was of Johnny visiting the inmates.”

Gressett relayed Green’s invitation to Cash, who eagerly accepted. Green helped sell the idea to the Folsom authorities. It took awhile to set up, but the unpublicized concert finally took place in November 1966, with Green himself serving as soundman. “He come on and did a terrific show and of course he was accepted [by the inmates],” Green said. “They just clapped and clapped and clapped for him.”

The show’s success seems to have inspired Cash to revive a pet project. For years he had wanted to record a live album at one of his prison shows, but his Columbia Records producers always vetoed the idea. Then, early in 1967, Cash was assigned to a new producer, Bob Johnston. When Cash pitched the prison idea to Johnston, he embraced it and made it happen. And so, on Jan. 13, 1968, Cash returned to Folsom with a truckload full of Columbia Records sound equipment to record “At Folsom Prison,” the live album that would transform his career.

Earl Green did not attend that second concert; he had been transferred to a minimum-security prison in Vacaville three months earlier. Nevertheless, he managed to play a key role in the proceedings. While still at Folsom, he had urged Glen Sherley to write a song for Cash. Sherley came up with “Greystone Chapel,” which echoed Green’s own discovery of salvation behind bars:

It takes a ring of keys to move here at Folsom

But the door to the House of God is never locked

Inside the walls of prison my body may be

But my Lord has set my soul free

Green recorded Sherley singing the song in the chapel, and slipped the tape to Gressett, who eventually played it for Cash. Johnny loved the song, and he performed it during his second Folsom concert, after pointing out Sherley in the audience as the man who wrote it. This performance was included on Cash’s live album, thus launching Sherley as a professional songwriter while he was still behind bars.

In 1971, Cash helped bring about Sherley’s parole and brought him to Nashville as a songwriter for Cash’s publishing firm, the House of Cash. Johnny also made Glen a featured performer in his touring stage review, “The Johnny Cash Show.” As a free man, Sherley went on to write “Portrait of My Woman” for Eddy Arnold, and he also recorded some albums of his own. Charismatic, talented and ruggedly handsome, Sherley seemed set for stardom in his own right.

Meanwhile, Earl Green had beaten the odds again: Despite his life sentence, he had become eligible for parole. Gressett asked him if he wanted to seek Cash’s help, but Green rejected the suggestion. He did not want anyone to pull any strings for him. He earned his freedom the hard way, by demonstrating over the years that he was no longer the man who had swung that baseball bat at Joseph LaChance’s head back in Matilija Canyon.

Paroled sometime in the early ’70s – the exact date is uncertain – Green followed his friends Sherley and Harlan Sanders (another parolee-turned-songwriter) to Nashville, where Green worked briefly as a DJ for a local radio station. He also worked (very briefly) at the House of Cash, in a make-work job that Johnny offered him “out of the kindness of his heart, like he felt I needed the money, which I did.”

Green never tried to reconnect with his long-lost sons, but he did marry again, and he helped his new wife, Sheila, raise her sons from a previous marriage. Green also tried to help his friend Glen Sherley, whose Cinderella story did not have a happy ending.

Ironically, Sherley’s main problem apparently was his pep-pill habit, the same addiction that had almost cut short Cash’s career, not to mention his life. Sherley grew sullen and withdrawn, and began to make threatening remarks that intimidated Cash’s other employees. “Back then he was taking them pills and John found out about it and that’s when John kicked him out,” Green said.

Spiraling downward, Sherley gave up on his once-promising Nashville career and returned to California. He had gone through all his money, he had few prospects, his wife had left him. One day in May 1978, he picked up a gun and blew his brains out. He was 42 years old.

“It was just sad, because Glen got on those pills so bad that they just controlled him,” Sheila Green told the Ojai Quarterly in a recent interview.

No such fate awaited Earl Green. He was content to work in a machine shop, and later as a sort of a handyman for the country stars Ricky Skaggs and Sharon White. “I was nanny to their children, and Earl, he did a little bit of everything,” Sheila said.

Sheila said she tried unsuccessfully to get Earl to write his memoirs “because so many things happened in his life. It would have made a real good book.”

Earl preferred not to dwell on the past. But he always remained very proud of the role he had played in helping to bring Johnny Cash to Folsom Prison.

“We stayed friends with Johnny,” Sheila said. “We went to dinners at their house.”

Earl also remained a churchgoer, and he remained married to Sheila for 37 years, until his death in Nashville in 2011 at the age of 84. Spared from the gas chamber, and from permanent confinement in Folsom, he had turned his life around and made it count for something. And that, more than the famous Johnny Cash concert, was his most impressive accomplishment.

“Of course I’m not the person who went into prison,” he told Streissguth. “I’m the person who come out of prison. And I changed. And I did that myself.”

(This story originally appeared in the spring 2013 issue of the Ojai Quarterly.)

Memoirs by Monica Ros, founder of Monica Ros School

In Her Own Words by Monica Ros

Transcription of Mrs. Monica Ros’s handwritten notes from approximately 1984-1986, including her autobiography, the school history, her teaching philosophy and the founding principles of the Monica Ros School.

EARLY DAYS

In what I consider, and I think my sisters would have agreed, our best remembered and formative years were spent when we lived in the then undeveloped area of Willoughby on the outskirts of the North Shore Line.

My name before marriage was Monica Horder. Margaret and I were born in Burwood, Australia in 1904 – 1901 respectively and from there we moved to Croyden, both suburbs on the eastern train line, and in 1910 we moved to a large two story house set in the middle of three acres of ground and named Greenacre. The house in Willoughby had been built by a gentleman, a Professor Pitt-Cobett (not sure of spelling) from England who taught at the Sydney University, and who lived at Greenacre in lonely state with his serving-man perhaps with nostalgia for England.

Patricia, known as Pat, our sister, was born in Croyden in 1909 so she was only a baby when we moved. How we loved that sweet and charming house! It was hung with convolvulus creepers and the front door, set in a small porch, looked out on the grass oval with a tall Italian cypress in the center. The gravel drive circled the grass and led straight to the front gate. On either side of the drive was a half-acre of rough grass (one became a tennis court later) and all was surrounded by an arboretum of trees and shrubs. There was a horse and carriage stable but we only aspired to pasturing our grandfather’s beloved old horse Graff for several years which we rode occasionally round the acre paddock. Mother developed a half acre of flower gardens on the east side of the house and from our bedroom window, on the same side, was a distant view of the Middle Harbour Hills and a bit of blue water.

Another feature of the area at that time was the extensive Chinese market gardens and I remember seeing these industrious people jog-trotting with their pails of water balanced on a pole over their shoulders. The water was derived from deep wells in the fields which in turn produced mosquitoes in appalling numbers which I remember doing battle with each night even in a mosquito net shrouded bed.

The extension of Edinburgh Road beyond our house was then a sandy, stony road, which wound down by a bush track to the waters edge. As children we were often taken on boating picnics, a rowboat being hired from a man who accommodated picnickers. We were often accompanied by cousins and by several young uncles, our mother’s younger brothers who taught us to row. Our father, who was a Londoner and twenty years older than our mother, did not feel at home on boating picnics and did not join us, but he liked us to have the fun. He did love Greenacre and I think the setting suited him with its overtones of an English country home.

Our mother had graduated from the Sydney University (not a very usual distinction for a woman then) and was a serious minded, gentle person and avant-garde in her thinking of the day. She married my father when she was twenty-one. She was really suited for an intellectual life, but devoted her energies to home making and seeing that her three girls have a happy childhood. At the same time she was able to follow her own interests and devoted time to writing papers and to the study of philosophical subjects and social change along with close friends of the same mind. While all were involved with husbands and families they shared this mutual desire to pursue philosophical, literary and social interests of the day. Naturally some of this rubbed off on us.

Our father, while primarily a businessman and so hard working, never interfered or opposed mother’s interests, but was devoted and proud of us all.