Ojai’s Cartoonist in Residence

By Jerry Camarillo Dunn, Jr.

To look at him, you might think he’s just another guy loafing around an Ojai coffee shop, staring into space. But if you could peer inside his head, you’d see that he’s hard at work.

Sergio Aragones is a cartoonist.

That chortling you hear as he doodles on his napkin? It means Sergio just thought of another gag for MAD Magazine, where he’s been a creative force of nature for more than 50 years.

It all began in 1962, when the fledgling cartoonist left his home in Mexico to try his luck in America. He arrived in New York with twenty dollars in his pocket and a portfolio of funny drawings under his arm. After learning that cartoonists visited the city’s magazines on Wednesdays to sell their work, he started making the rounds. “Your cartoons are crazy!” everyone said. “You have to take them to MAD. That’s where they belong.”

MAD was the nation’s top market for silly pictures, but the 24-year-old cartoonist screwed up his courage and appeared at the magazine’s office. The editors took his samples into a little room . . . and there was a deafening silence. But at last Sergio heard guffaws of laughter echoing off the walls. His cartoons were a hit, and they’ve been off the wall ever since.

The editors assembled some of Sergio’s wordless gags into a two-page story about the U.S. space effort. One drawing showed a space capsule in orbit with a dismayed astronaut in the window, watching a paper airplane sail past.

“I wanted to sell MAD more drawings,” Sergio recalls, “and I saw all the empty areas around the borders of the pages.” So began the legendary “Marginals,” gags that Sergio tucks into the white spaces throughout the magazine. The only thing not marginal is the humor.

Sergio characterizes himself as a “writer who draws,” and each Marginal is a short story in itself — like the drawing of a bearded psychiatrist so absorbed in taking notes that he doesn’t notice his patient leap off the couch and out the window.

MAD’s editors thought the Marginals were a cute idea but couldn’t last long. They told Sergio, “Well, we’ll publish them until you run out of ideas.” Since then his work has appeared in every issue except one. (“The post office screwed up.”) Over nearly five decades, he has drawn thousands upon thousands of his trademark wordless gags.

In fact, Sergio is reputed to be the world’s fastest cartoonist. He is definitely the most honored, having won every major award including the National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben, which is the Oscar of the field.

Even as a schoolboy in Mexico, where his father eventually relocated the family after leaving Spain for France during the Spanish Civil War, he was always drawing funny pictures in class, which entertained his pals and exasperated the teachers. (“Sergio, pay attention!”)

He also developed his imagination by playing make-believe, but in a way most kids could only dream about. His father was a movie producer at Mexico City’s Estudios Churubusco. “Whatever movie they were shooting, that’s what I played. If it was cowboys and Indians, I’d go to the prop department and get myself a big hat and a set of guns,” Sergio says. “The western town was my favorite. In front of the cantina was a railing for the cowboy actors to tie up their horses. When there wasn’t a movie being made, I loved to go there and challenge invisible bad guys. I’d come banging out through the cantina doors, get shot, flip over the railing with my legs in the air, and land in the dusty street. Then I’d do it again and again — because I was a kid!

“Your imagination really goes wild on a movie set. I think it helped my cartooning later on, in thinking up ideas.” His formal schooling continued at the University of Mexico, where Sergio studied architecture. “But my friends were actors, artists, and directors,” he says. “I learned pantomime from Alexandro Jodorowsky,” the avant-garde filmmaker. “I wanted to study pantomime so I could apply it to my cartoons. I love cartoons without words! They’re like silent movies.”

When Sergio announced his intention to be a cartoonist, his father was terrified because cartoonists don’t always make a great living. At age seventeen, though, Sergio started selling his work professionally when an art teacher sent his drawings to the Mexican humor magazine Ja-Ja. “I realized that cartoons have to be published for people to enjoy them,” he says. He also realized that America offered a much larger market than Mexico for his drawings.

Soon after his arrival in the U.S., Sergio began writing scripts for comic books — ranging from House of Horrors to Young Romance — for the top publisher in the field, DC Comics. By the early 1980s, he decided to launch his own comic book.

Groo, the Wanderer is a takeoff on the “sword and sorcery” genre, particularly Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian. Sergio’s writing partner, Mark Evanier, describes the main character as “an ugly, large-nosed buffoon of surpassing ignorance who constantly misunderstands his surroundings. Possessed of superlative skills in swordsmanship (the only task in which he’s remotely competent), he delights in combat but . . . unfortunately he is also indiscriminate and incredibly accident-prone, and despite generally good intentions causes mass destruction wherever he goes.”

With Groo, Sergio took up a new artistic challenge. He explains the differences between his two chosen formats: “Comic books are a mix of storytelling and drawing — sequential art, panel after panel. A cartoon is a compressed idea; you simplify it to the maximum. You can tell a story in a whole comic book, or take panels off until you have just one. Then take the dialogue off, and in one panel, without words, you have a whole story! That’s why I think pantomime is very impressive.

“A comic book, on the other hand, is like a mini-movie. You write, direct, act it out, tell the characters what to do, design the scenery and the costumes. I feel fortunate to have my own little universe.”

Sergio’s artwork in Groo may start with a “splash page” depicting a medieval village, hundreds of people in different kinds of garb, animals, wagons, tools, and weapons. All the details are painstakingly researched for accuracy in National Geographic and the cartoonist’s library of visual reference books.

Sergio also sneaks in his own feelings about issues of the day. “A comic is a great vehicle for helping: pollution, deforestation, women making less money than men, and other social problems. You realize you have a good platform for making a comment, and you use it.

“I wanted to criticize television in an issue of Groo, and it took me forever to figure out how to do it. There was no television back in barbarian days, so I finally used puppetry, a Punch and Judy show. Groo, with his violent tendencies, invents violence on television, not to mention TV dinners and commercials.”

The whole town gets hooked on puppet shows. In one scene a kid tries to get his parents to look at the beautiful sunset. Shhh! they hiss. We’re watching! “Kids love the silliness of the whole thing,” says Sergio, “but they also see how damaging television can be. I hope they ask questions of their parents.”

These days Sergio also works as a guest artist for The Simpsons comic books, writing and drawing whole issues by himself. And he’s writing a series of tales from his own life, a sort of comic-book memoir called Sergio Aragones Funnies. “I’m fortunate that I’ve met a lot of remarkable people,” he says. The stories depict his encounters with everyone from Richard Nixon to a high lama in Tibet. One story tells about meeting the famous cellist Pablo Casals in Acapulco.

Always curious, Sergio has traveled broadly and radiates the sophistication of a citizen of the world. Spanish and French were his first two languages. (His old friend Mark Evanier jokes that Sergio “does to English, his third language, what Picasso did to faces.”)

For many years he visited far-flung places such as Kenya, Paris, Hong Kong, Tahiti, and Venice with the staff of MAD. The publisher, Bill Gaines, organized a free trip every year for the magazine’s regular contributors — the cartoonists, writers, and editors listed on the masthead as “The Usual Gang of Idiots.” Once, when they traveled to Haiti, Gaines had the whole group driven directly to the house of the magazine’s one and only Haitian subscriber, where he formally presented the baffled man with a renewal card.

But Sergio’s heart belongs to Ojai. “I had always lived in a big city,” he says, “Mexico City, New York, Los Angeles. When my daughter, Christen, was very young and we came from L.A. to Ojai in 1982 for her to attend Oak Grove School, I never thought I could live here. But it took me no time to realize how comfortable, how conducive to thinking, it was. I loved it almost immediately.”

Sergio donates his time all over town, generously speaking to school kids and drawing cartoons for posters, the Ojai Library wall, and just about any group that asks. “You feel so much a part of the town,” he says. “It’s fun belonging.”

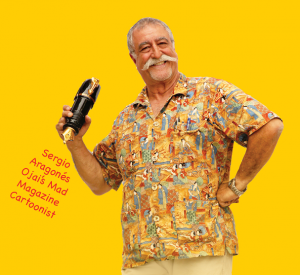

Sergio is a familiar figure around Ojai, usually dressed in shorts, his guayabera shirt untucked and pockets bulging with pens, his gray hair in a ponytail, his familiar moustache as wide as his smile. Greetings follow him down Ojai Avenue, and everyone feels they know him.

His warm feelings for the town led him to mount a retrospective exhibition of his work at the Ojai Valley Museum in 2009. “My art doesn’t really fit in a museum,” he points out. “I felt people might not understand the drawing of a cartoon, so I was always reluctant to exhibit. But Ojai is like showing my work to friends and family.”

The museum’s exhibit hall looked as if there had been an explosion in a comic book factory. An astonishing variety of Sergio’s work was on display, starting with his boyhood sketchbooks and continuing through his nearly 50 years at MAD, as well as his stint as a performer on television’s classic comedy show Laugh-In, illustrations for national advertisements, and cases displaying his hundreds of comics and books. (His recent anthology, MAD’s Greatest Artists: Sergio Aragones: Five Decades of His Finest Works, is already in its third printing.)

The cartoonist did one thing that museums definitely frown on: He drew all over the walls. “One of the basic ideas for a MAD Marginal is the corner cartoon, where the borders of the magazine connect,” he explains. “Something is coming from one way, something is coming from the other way, and you know what’s going to occur if they meet: A criminal is trying to hold somebody up on the corner, and a bunch of policemen are coming from the other corner. Your imagination fills it in.

“Well, there were a lot of corners at the museum. I could draw on a physical corner, putting a cartoon on each side, and visitors could see what was going to happen. It was perfect!”

On a narrow wall Sergio arranged three of his framed awards in a vertical line. But he hung the fourth one cockeyed and halfway down to the floor. Then he took a black marker and drew cartoon “speed lines” down the wall to show that the frame was falling. Below that, he drew a guy getting whacked on the head with a corner of the frame.

Sergio often subtly incorporates Ojai in his MAD cartoons: the Arcade, Starr Market, a kid on the street wearing an Ojai T-shirt. “Every chance I get!” he says, chortling.

If you see Sergio Aragones around town, say hello — that is, unless he’s sipping coffee and doodling on a napkin. Then you know he’s at work. “Well, it’s not really work,” he says. “Cartooning is a state of mind . . .”

(This story originally appeared in the Fall 2011 issue of The Ojai Quarterly. Republished here with permission.)