In Her Own Words by Monica Ros

Transcription of Mrs. Monica Ros’s handwritten notes from approximately 1984-1986, including her autobiography, the school history, her teaching philosophy and the founding principles of the Monica Ros School.

EARLY DAYS

In what I consider, and I think my sisters would have agreed, our best remembered and formative years were spent when we lived in the then undeveloped area of Willoughby on the outskirts of the North Shore Line.

My name before marriage was Monica Horder. Margaret and I were born in Burwood, Australia in 1904 – 1901 respectively and from there we moved to Croyden, both suburbs on the eastern train line, and in 1910 we moved to a large two story house set in the middle of three acres of ground and named Greenacre. The house in Willoughby had been built by a gentleman, a Professor Pitt-Cobett (not sure of spelling) from England who taught at the Sydney University, and who lived at Greenacre in lonely state with his serving-man perhaps with nostalgia for England.

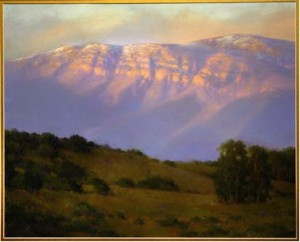

Patricia, known as Pat, our sister, was born in Croyden in 1909 so she was only a baby when we moved. How we loved that sweet and charming house! It was hung with convolvulus creepers and the front door, set in a small porch, looked out on the grass oval with a tall Italian cypress in the center. The gravel drive circled the grass and led straight to the front gate. On either side of the drive was a half-acre of rough grass (one became a tennis court later) and all was surrounded by an arboretum of trees and shrubs. There was a horse and carriage stable but we only aspired to pasturing our grandfather’s beloved old horse Graff for several years which we rode occasionally round the acre paddock. Mother developed a half acre of flower gardens on the east side of the house and from our bedroom window, on the same side, was a distant view of the Middle Harbour Hills and a bit of blue water.

Another feature of the area at that time was the extensive Chinese market gardens and I remember seeing these industrious people jog-trotting with their pails of water balanced on a pole over their shoulders. The water was derived from deep wells in the fields which in turn produced mosquitoes in appalling numbers which I remember doing battle with each night even in a mosquito net shrouded bed.

The extension of Edinburgh Road beyond our house was then a sandy, stony road, which wound down by a bush track to the waters edge. As children we were often taken on boating picnics, a rowboat being hired from a man who accommodated picnickers. We were often accompanied by cousins and by several young uncles, our mother’s younger brothers who taught us to row. Our father, who was a Londoner and twenty years older than our mother, did not feel at home on boating picnics and did not join us, but he liked us to have the fun. He did love Greenacre and I think the setting suited him with its overtones of an English country home.

Our mother had graduated from the Sydney University (not a very usual distinction for a woman then) and was a serious minded, gentle person and avant-garde in her thinking of the day. She married my father when she was twenty-one. She was really suited for an intellectual life, but devoted her energies to home making and seeing that her three girls have a happy childhood. At the same time she was able to follow her own interests and devoted time to writing papers and to the study of philosophical subjects and social change along with close friends of the same mind. While all were involved with husbands and families they shared this mutual desire to pursue philosophical, literary and social interests of the day. Naturally some of this rubbed off on us.

Our father, while primarily a businessman and so hard working, never interfered or opposed mother’s interests, but was devoted and proud of us all.

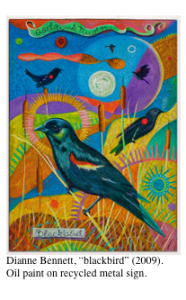

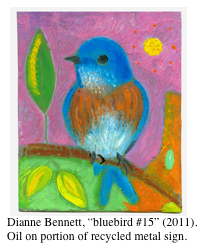

He really loved music and while he had no actual training beyond singing as a young boy in St. Paul’s choir in London he was sensitive, appreciative and supportive of my interest in music and was always happy for me to play the piano for him. Later he bought me a beautiful violin from my teacher who had purchased it in Brussels when on tour. And later, too, he built Margaret a little studio where she could work at home. She studied at the Julian Ashton art school in Sydney. His spending money in this way was indicative of his cooperation with mother to give us the where-with-all, within his means, for us to make progress in our chosen vocations. It was always understood, too, that we were eventually to be self-reliant financially. Otherwise, we were very limited as to clothes, entertainment and lived very simply at home and were rather serious minded though loving a good time, but most unsophisticated socially.

During our years at Greenacre the tennis court was made on one of the large grass areas either side of the driveway – a big expense for our father – which provided reciprocal entertainment at home with friends. There were tennis afternoons and evenings when everyone stayed to supper and an evening of music followed provided by our respective talents. Our cousins at Chatswood were our model. Tennis on Saturday afternoons at their home was wonderful topped off with supper and musical evenings and dancing on the verandah. As we had no brothers, except an older step-brother who was not much at home as he had taken up going on the land, which was a drawback socially for us, but with our cousins we met their fellow school and university friends and so a congenial group was formed. Tennis courts were prevalent in those days which provided a great deal of social life for families in a round of invitations of this kind.

Summer holidays were spent usually at the seashore where a house was rented, sometimes together with our cousins, sometimes separately. Friends were invited to stay and the entertainment was the beach and surfing. Father came during week-ends. I do remember when we were quite young at Greenacre driving in a four wheeler cab with assorted cats among the luggage over French’s Forest to Collaroy on Pittwater or some such place. The Blue Mountain with marathon walks up and down gullies, was another holiday resort.

For ten years or more we lived in this rather self contained and isolated environment though one with cultural motivation. There were always books, reading aloud and an interest in music and art. Our home also provided a source for the love of reading and acquaintance and taste in literature and the arts. Plays were our passion and took up a large part of self-entertainment during the holidays with cousins and friends. The script was usually original and anything at hand provided costumes and stage props. There was a captive audience of mother, aunts and friends. I am sure the work in my school in later years in children’s dramatics stemmed from those early years of remembered delight.

We were taken for one glorious outing a year to the theatre, a never forgotten treat, to see plays such as Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, the Blue Bird, and so on. Once, I remember, we saw a big circus when a client of our fathers presented us with tickets! Later Mother would take me to orchestral concerts and recitals once my interest in the violin was established. A fellow violinist and I would spend afternoons playing violin duets together or spending much time rehearsing in a string ensemble organized by our teacher and so on.

It became apparent as Margaret and I grew older that our interest definitely lay with drawing and music. Our parents were far sighted enough to encourage this, so in spite of limited means – World War I soon disrupted my father’s business – money was put out for drawing and music lessons and private education. Also it was always understood and accepted that we should try to eventually become largely financially independent. Pat, who was much younger than Margaret and myself and while very musical, but on leaving school Pat took up secretarial work, though later reverted to music and the theatre.

SCHOOLING (Young Miss Monica’s)

With the exception of a few years when I attended two different small private schools and until my early teens, schooling was carried out by a governess and later with a small group of children who lived in the same locality. When very young in Burwood I attended a (kindergarten) private infant’s school, as they were called then, a short distance from home. On moving to Boyden, where Pat was born, I had a governess, a Miss Davidson, who came to our home to give me lessons.

Perhaps an anecdote is timely here because it shows Margaret’s flair for language, humor and charm at an early age. Mother had come to the study with Margaret, then barely three, I’m sure, to see me settled in with Miss Davidson. When the time came to leave, Margaret loath to do so was enticed by suggesting that she pick up her teddy bear and take him out doors. “Oh!” she exclaimed, thrust the little beast outside. I can see mother laughing now. As she guided the child out by the door.

Later I joined a family of children, two boys and two girls, for lessons with the same governess. We had lessons in their big nursery play-room. Margaret was still too young to join us being three years younger than I. I have a vague recollection of beginning readers and doing sums, but I do remember vividly when one day I found I could read Guy of Warick all by myself.

Next, when eight or so, I was sent to a school in Strathfield called Meriden. It was a long journey, which involved a walk to the train station where the train took me to Strathfield. I remember very little except that there were lots of girls and I was very shy. One girl became a life long friend and we visited each other’s homes during holidays even when we lived far away from each other. It was certainly a long journey to Homebush from Willoughby and vice versa. We shared the same interest in imaginative occupations.

What schooling Margaret had at this point I do not know. Perhaps Miss Davidson or mother attended to it. About this time, I came down with a severe illness and was in bed eight to ten weeks. It was soon after I was able to get about a little that we moved in 1910 to Willoughby and to live at our beloved Greenacre home. As a result of the long confinement I had to learn to walk again and recall distinctly trying to meet my father as he came home from work. How long the front drive seemed!

When at Greenacre we first attended a private school in Chatswood named Astrea, which entailed a walk to the train, which took us to Chatswood. Some time later it was decided that Margaret’s and my schooling should revert to a small group of children taught at home. We were enrolled with a brother and sister of our own age to have lessons with a governess named Miss Caroline Whitfeld a charmingly, cultivated woman with a gift for stimulating interest in literacy and historical subjects in particular and encouraging creative writing, but always with an eye to grammar and spelling. Later the group of children was enlarged to eight – all girls then some of whom became life long friends – came to Miss Whitfeld’s home for lessons where rudimentary school rooms were created and morning exercise were held in the hallway.

There was French and little plays given for our parents in French. I was always poor at sums, but remember laboring through long division. I believe it was Miss Whitfeld who really drilled the times tables into one. To Miss Caroline Whitfeld we owe a great deal of our early education.

Miss Whitfeld had two sisters living with her and one, Miss Harris, wrote and published teen age stories and also taught drawing in which Margaret and I participated. I do remember still life attempts, but I think possibly the greatest influence Margaret had was from a little girl named Helen Young who had a talent for drawing ponies and horses. We would stand around her at recess and beg her to draw for us. The ponies she told us were brumbies. Recess was taken in a small adjoining field – no play equipment, we had our own games. We sang songs together Miss Whitfeld playing the piano. This socially simple, but educationally sound schooling in a limited way has had a lasting effect on our lives. My cousin, who was one of the group, still writes in her letters to me, when referring to something she had written Miss Whitfeld would not approve of that construction!

This small and protected personal school environment was left behind when in 1916, I first and Margaret later was sent to the Redlands on Military Rd. Mosman, a school which is still flourishing in a northern suburb of Sydney. In my day the principal was Miss Gertrude Rosely whom one thinks of “with gratitude as a guide, counselor, friend and an inspiration to live a good life as well as a teacher of formal education. To quote from a recent retrospect celebrating Redland’s centenary. Miss Rosely resigned in 1945 and the school is now run as a Church of England School. There, a very good teacher, a Mr. Collins, was teaching and I’m sure Margaret must have made her mark when she entered his class, because she continued her studies with him after leaving school.

By then I had taken up the violin for some years. Much time in my school years was spent studying music as well both piano and violin though the violin became my principle instrument. For some years I had been studying violin with a teacher named Mowat Carter who was well known in Sydney. This entailed trips to town for lessons after school. It was a long day via a ferry boat. He was not attached in any way to the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, which was, and still is the foremost school of music there.

Later I attended the Conservatorium the main purpose being to prepare myself for teaching, violin in particular to children. This deep rooted feeling and interest I had for children to have a well grounded, sensitive and appropriate beginning in learning a musical instrument was carried over much later when the Monica Ros School was formally founded in 1944 at the present site with a curriculum that allowed for a child’s creativity, learning, growth and happiness through musical experiences as well as the recognized academic needs.

LATER YEARS

World War I was still in progress, our brother and uncles had enlisted and been sent overseas. Except for that and the stringent economy at home, life seemed to go on for us as usual though I do remember being emotionally distressed and un-nerved at a lot of the news, and especially when cousins and friends enlisted.

World War I was over in 1920 and the main reason for selling Greenacre in 1921 was moving to a small house in Roseville on the North Shore train line. It was more practical as we grew older to be within reach of easier transportation to and from the city since our lives were devoted almost entirely to our respective interests of music and art and the accompanying social interests. Father later bought a house in Roseville on the west side of the train line and we lived there for six or seven years.

When we moved to this house named St. Margaret’s by a previous owner, Margaret had begun her studies with Julian Ashton. I do picture her now how she would start off for the train dressed in the acceptable art-school fashion of a chintz overall type dress, her huge folder of drawings under her arm. As children at Greenacre we spend countless hours in our playroom painting, coloring, drawing and writing stories, but Margaret definitely was always the one who wanted to and could draw. I remember one instance that made her talent clear to me. I had taken a sketch pad and pencil into the garden to make a drawing of the house and it was awful, so dead and mechanical. Margaret came along and in a few strokes produced the house and its charming atmosphere. I knew I would never be able to do likewise however much I appreciated drawing and paintings.

It was while living at St. Margaret’s that Margaret had her illustrated joke accepted by the Bulletin and she was sent to Melbourne by Mr. Wheeler to work on his paper. I do remember she had a new coat and hat for the occasion and I thought how brave she was to go off like this by herself.

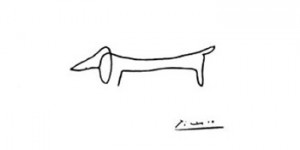

Margaret was pretty with thick brown hair that had a wave and was smaller in stature than I, perhaps 5 ft 4 inches. We were always dressed alike as children and of course at school we wore the school uniform of blue serge skirt and midi or blouse. Our clothes were all made at home and I later took up sewing and made a lot of my own clothes. From an early age Margaret suffered from asthma, often severe attacks, but it never dampened her lively spirit and an innate courageous outlook. At school she was not above practical jokes to the embarrassment of an older, more proper sister when a reprimand was administered. Of my mother’s influence in an artistic way I have no recollection of her ever painting or sketching at home, but I do remember with what admiration I would look at a large canvas hanging in our grandmother’s living-room wall of a woodland scene and stream and being told mother painted that. Otherwise our home atmosphere supplied the rest of our influence. One of our uncles, who became an architect, would write us letters always illustrated with knights in armor which we loved. There was no question about it, Margaret always wanted to be an artist and draw. I think Margaret’s words in reference to her own artistic talent are best said in her own way – books and pictures seemed to go together all my childhood. If I wanted to draw all my life, which I did, then books seemed the proper place for drawings to go.

Music was my love. I was first taught piano by an aunt, my mother’s sister and a good pianist. At five years I had my first piano lesson and showed off by demonstrating how I could play a chromatic scale, though I had no idea what a chromatic scale was but probably liked the sound I played and studied piano on and off for years. Spending hours at the piano practicing and playing through all kinds of music. I don’t know why it was decided I should learn the violin. Thirteen was too late to begin, but I became devoted to the struggle. I was not a well-known violinist as Margaret has written, just a devotee of the instrument and a plodding student. I attended the Conservatorium of Music and along with orchestra, chamber music and theoretical work I studied with a different teacher and it was the beginning of a good understanding of technical differences, which had hampered my playing heretofore. From then on I never swerved from an interest in teaching children and beginners and laying a sound foundation as well as deriving pleasure from learning to play violin or piano. Another teacher at the Conservatorium with whom I studied also specialized in these same teaching ideals especially where young children, were concerned. Children I have always related to.

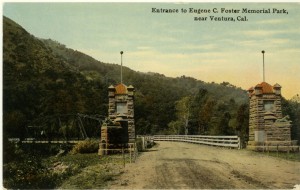

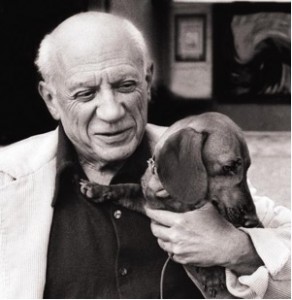

I married Ricardo Ros a Theosophist from Havana, Cuba in Sydney in 1927. At that time we were both members of the Theosophical Society, but we also had a great interest in the teachings of Krishnamurti, so after a trip to Madras, India to attend a Theosophical convention we decided on our return to Sydney to go to Ojai, Calif. Our main interest being to hear Krishnamurti, the now well-known world philosopher and teacher who spoke regularly in Ojai where he had a home. Ojai is where Krishnamurti’s first camp, as it was called, was being held in the spring of 1928. Later we went to Havana, Cuba to stay with my husband’s family. That was during the Machado regime. After almost a year we returned to Ojai in April 1929 and Margaret joined us here in Ojai. She had come over with friends from the theosophical group who at that time were interested to hear Krishnamurti. Margaret had an invitation to visit friends in Holland which she did and then made her way to London.

The first Ojai house we lived in was a charming building on Eucalyptus St., later pulled down for more modern dwellings and rented, I remember, for $25.00 a month in those early depression years. When there was a vacancy we moved to Krotona to live. But then came “the break” which necessitated moving from Krotona and resigning from the Theosophical Society. It was at that time in the early thirties that the depression struck Cuba severely as well as everywhere else, so that my husband’s income was sorely depleted and capital investments were lost in the U.S. also. So it was then I began forming a class of violin students and my husband taught Spanish at Thacher School when Dr. Barnes was headmaster. Among my first violin students in Ojai was John Perkins, son of Margaret Perkins Baker and Louise Butler daughter of Dr. and Mrs. Charles Butler well-known residents of Ojai.

During this period in the early thirties I took time to resume studying violin with Louis Kaufman in Los Angeles and later took piano lessons with Elizabeth Cofee, an excellent piano teacher who had come to live in Ojai with her friend Rebecca Eichbaum. These two women contributed much to the musical life in Ojai for many years. Musical activities for me centered in playing string quartettes at Edward Yeomans home with other Ojai players. Regular gatherings for quartet playing for our own enjoyment were held there. The players being Edward Yeomans Senior, cello, Agnes Gally, Violin, Forest Cooke of Thacher, viola and myself violin. Often, too we supplied music for school programs at O.V.S. and Thacher.

In the summer of 1937, I was able to make a short trip to see my sisters who had left Australia to make their home in London. My husband left for Havana Cuba at the same time. Never a strong person it was there he underwent surgery and when we both had returned to Ojai we went at once to San Francisco where Ricardo underwent radium treatments – the forerunner of chemo therapy, I presume. Back in Ojai we lived in what is known as the Bauer house on Grand Ave. I don’t remember the rent, but it must have been very little compared to today’s rents for owners were delighted to have their properties occupied at all.

My husband only lived a short while dying October 9, 1939. Shortly thereafter I went to Havana to be with his family. That was during the Batista dictatorship. I remember seeing him once with his family at a concert. Jasche Heifetz was playing at the Paliacio de Bellas Artes. Which reminds me of the coincidence when I was in Havana first in 1928. To my amazement a concert was advertised to be given there by Henri Verbruggher string quartet. This quartet had been in residence at the Conservatorium of Music in Sydney for years and one of the players was my former violin teacher.

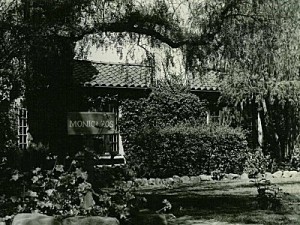

In the late spring of 1940 I returned to Ojai to the same house. I had to set to work to augment my income and the natural thing was to begin teaching music again. Besides piano and violin lessons a group of children came for music classes which consisted of singing songs, rhythmic and dramatic play in which all participated at a level in which a child’s imagination and ability could have free rein and the quality of pretend is uppermost. It was from that time my school was founded in 1942 in Ojai which had its beginnings in classes devoted to the enjoyment of songs, dramatic play, rhythms, dancing at the level of nursery school age children. The house had an exceptionally large living room ideal for free movement and games. I remember some of the first children coming wonderingly through the front door that opening morning: Anne Thacher, Betsey Hart, Priscilla Tippet, to name a few to have music. These classes developed into the first Nursery School in Ojai and then on to Kindergarten and the lower grades.

Here would be a good place to tell of the group of actors who came about that time to live in Ojai. They called themselves the Chekhov Players and were a creative and talented group, Iris Tree and Alan Harkness being two of the guiding lights. The plays which they produced in Ojai were exceptional.

I mention this group because one member named Hurd Hatfield offered to help me with the children’s classes. Story telling, fun and nonsense dancing, painting and dramatizations were all in his line. By this time the first music classes had developed into regular morning activities of a nursery school order. I remember that to commemorate Thanksgiving Hurd painted a large freeze of pictures depicting the Pilgrims who left England and came to America because the King would not let them have any ice cream was the story. No matter. These classes developed into the first nursery school in Ojai and then on to Kindergarten and the lower grades.

It was June 5, 1942, that I took my U.S. Citizenship in the Ventura Courts, Margie (Perkins) Baker being my sponsor. And during that summer of 1942, I traveled to Seattle when I stayed with friends and attended summer courses of nursery school procedures at the University of Washington as well as taking further piano study. Live piano playing to me being a desirable basic instrumental requirement for nursery school music.

Due to the request of parents and of Mrs. Anson Thacher in particular, who was very interested and supportive, the first advertised Ojai Nursery School was established and operated in these surroundings, for until 1944. I remember a sand box and slide being installed and a swing, Mrs. Aino Taylor, wife of John Taylor who was later principal of Nordhoff High School, assisted me as the class grew and Mr. John Ascott, who formerly worked at O.V.S., would come and help the children with wood-work in a little open sided shed lovingly called “the shop.” Seated activities, for the most part, took place on the extensive L shaped out-door porch with ran the length of the house. One dramatic event which took place one night during this time at the Bauer house was a fire in the big living-room. A pet cat, who was sleeping indoors and who woke me up by rushing and jumping about the room, saved the situation. The fire trucks came and in the meantime I had used the garden hose. Fortunately the fire was contained at one end of the room though the piano was damaged by heat and I lost many books. It was thought that sparks from the fireplace caught some clothes that were left to dry, but faulty wiring was also considered. Having music in the non-blackened area is still remembered by Anne Thacher who reminded me of the incidence.

One picturesque occasion worth recalling was the arrival at school in the mornings of Sally and Donna Gorham in a pony cart until the school was moved to McNell Road. Parents brought and called for their children and they came mainly from the east end of the valley.

A forerunner of dramatic performances took place at the school on Grand Ave., too. Del Garst reminded me once how he was the prince galloping to the tower to rescue the princess, and I believe Mr. Ascott constructed the tower from which the princess looked from a window.

The very first brochure of a diminutive size reads Ojai Nursery School. An outdoor school for children 2 to 3 years of age stressing music, rhythms and social training. The monthly fee for 5 mornings was $15.00 and the hours 9 to 12. There was a description of having activities in the outdoors as much as possible either in the garden or on the porch while music and rhythms were conducted in the large living room. Because of the California climate making things possible, outdoor activities were always a feature of the school and continued to be from there early beginnings. I dwell in these things because the atmosphere was established then for a child’s world and needs and was carried over to the next home much later years.

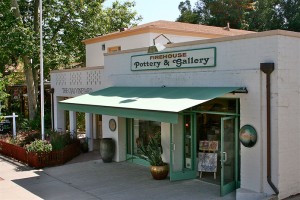

1944 to 1968 – MONICA ROS SCHOOL

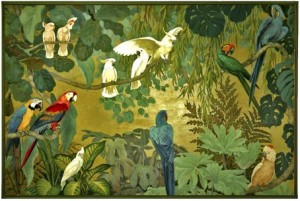

It is fortunate indeed for the Monica Ros School which began as the Ojai Nursery School and Kindergarten on Mc Nell Road to have had its beginnings in a semi-rural community, than present. Tree shaded and rather undeveloped outdoors, where as well as using some basic outdoor equipment the children could run and play freely and enjoy their own creative games. With plenty of rocks on the school grounds but also many trees and shrubs. There was even a bird watching area took and with the climate that favors outdoor activities the out doors became a classroom in many instances where children could develop and enjoy the contact with their surroundings. This love of school surroundings I remember was reflected once when a child exclaimed when a diseased Acacia had to be removed “Oh Mrs. Ros you’re ruining the school.” So it can be said that the basic philosophy, if you want to call it that, actually arose from the happy relationship the children and teachers had with each other and their surroundings. Also, the exciting small houses used as school houses, while inadequate in many way, brought an atmosphere of homelike informality which compensated for a made to order school room, however well designed.

I have always maintained that “right beginnings” were essential to ensure understanding of a subject and to develop necessary skills. This was based in my realization that my own beginnings at one time were inadequate to learn what I needed and when I found that I could learn with a teacher who imparted the necessary guide lines, I vowed then that I would learn to teach with skill and understanding “right beginnings” (at that time, a musical instrument in particular).

I wanted them to have right beginnings, an education that reflected not only appreciation of things to be learned, but to have good values, good relationships and of the finer responses brought about by the exposure to music in particular and all it’s related interests and skills. These skills spoke for itself in the happiness as it was reflected in the children’s flowering during their early years.

Also my wish was always to be able to include children of various socio-economic environments and therefore scholarships were offered, sometimes in part or on a reciprocal basis, to those children who in my judgment would benefit from the school as well as the school from the children. In this respect I do not find in any scrap book one announcement of a fund raising event that did not have as its aim the scholarship fund. It brought a spirit of helpfulness between people and was never regarded in any other light.

To learn with a love of learning, without competition, to take responsibility, to appreciate another’s ability, to cooperate in the enjoyment of the marvelous make-believe of play-acting with costumes and music and dancing was my wish for all the children to experience and above all music. Singing together regularly and musical appreciation, all of which created a harmonious atmosphere as well as discovering individual talents.

Because of interest in music and training as a teacher of young children, it seemed only natural, when the school opened on McNell Road that presenting music in a variety of forms should be a part of the curriculum on a daily basis. The sturdy secondhand piano was purchased for $50.00 and lived under a tarpaulin in the pergola. It was a focal point for singing daily during the week, and for dancing, dramatic play and rhythms from the three-year-olds on up.

As to the related area of folk dancing, it helps a child rhythmically to improve physical ability and to gain interest historically about the country from which the dance comes. Singing in dramatizations give poise, self-confidence, aids memory, and teaches getting along with others. Comradery is formed by children singing together. By helping children release stored-up emotional and physical pressure, music assists children in their concentration on the basics reading, writing and arithmetic.

To return to fund raising events I should like to mention the annual fiesta of those days. This included the caring dedicated help of parents as well as staff. Parents gave such support and encouragement to the little school. These affairs were aided by the children themselves, each contributing for sale something of their own making such as a painting or some little ceramic work of art. It was always accepted by them as something they did to help their school. There was usually a little program of some kind, too, again by the children.

I should like to name everyone but will have to content myself with mentioning those who contributed so much to the early life of the school also have names not already given credit. Mrs. June Roller was a valued music group teacher. Mrs. Nell Roest, Mrs. Helen Cooper as nursery school teachers. Betsy Pfeiffer who was an outstanding first and second grade teacher. I myself taught third and fourth grade when first and second had their own teacher. Jean Yeats carried on after Betsy left and who carried out experiments in the kitchen showing the presence of air on a heated empty can which crumpled before our eyes! Caren Proctor and Rupert Carr who taught shop. Mrs. Barbara de Creft whose outstanding gift was painting and where mother, Mrs. James Moore had taught before her and when planned and carried out with a stereo _____(?) lecture a children’s art show held at the Ojai Art Center was in 1953 with work from the children ranging from 5 to 10 years. An artist in her own right who really inaugurated the school’s outstanding art work. Science was first introduced formally by Da_____(?)Ersol who came to the school and donated to the classroom and intricate model of the sun and the planets. And there was Fred Maurer (?) and his brother, students from Ventura College who attended classes and in the early _____(?) who introduced his class to biology and took a very popular sports period. Woody Chambliss who helped with the finishing touches of plays, and sometimes necessary narrations.

As the Monica Ros School was run as a private business there was no board of directors but the staff met once a month after school for tea to share their views and ideas and to discuss what was taking place in the school. Any problem that may have arisen. Of course in running a school there were anxious moments, financial worries and a lot of hard work connected with such an endeavor, but I know with the dedication of staff and of parents the school is indebted to so much of the happy and enriched early childhood education which they helped me carry out. But I know that only with the help and dedication of parents and staff was I able to carry out my hope of providing “right beginnings” for children at Monica Ros School, this is no boast: I have been told over and over by children and now grown and parents of the lasting and happy and helpful experience it provided. Much of the charm and development of the grounds can be attributed to Mr. Bryan King. Besides all of the regular work, he developed a lovely rose garden outside my house, he was responsible for keeping the grass play area in condition, picked hundreds of persimmons which were sold and of his own volition for each Xmas program. Clientele of friends of the school who have remained faithful throughout the years and who attended these occasions: There was Connie Wash and Patsy Eaton, the William McCachey’s, the Anne Thacher, Helen Griggs, John Marillo (?), Elizabeth Thacher, Joni Friend who made an owl costume for her daughter Anne (when The Owl and the Pussy Cat was performed) of individually sewn brown paper feathers. The Herman Guttman’s who constructed and _____(?) the school’s first jungle gym (still in use). Barbara Griggs who helped with dramatics, sewing costumes and especially when her daughter Curry Griggs, the cow in The King’s Breakfast. Mr. and Mrs. Bill Myers, Nancy Myers always helping me I remember in particular at Bake Sales held when the Tennis Tournament was in session. In the very, very early days Babette Ferrer helped with her casting of plays. The William McCachey’s and I must mention here one of the first performances at the school’s new location which was Peter and the Wolf because Robert (Calder) Davis reminded me he was the Duck. I should like to include here the name of a friend of the school, Mr. Harry Sinclair who attended that performance and I think was the first donor of a whole scholarship to a child in the school. I remember Beatrice Wood donating a piece of her lovely pottery for a raffle and Ellie Hyman who would _____ and give readings to the spellbound children or tell stories she was a ___ ____ and when husband Paul Hyman who’s bookkeeping services were gratis. There was Howard Gally who made the first set of building blocks for the school two of which are still in use in the Kindergarten room big enough for children to get into. _____(?) a bell and _____(?) A product of Sue Beck’s imagination and carpentry talents. Other names Mrs. Florence Baldwin, Jean Post, Shirley Brown, June Roller, Nel Roest, Michael Ehrhardt, James Loebl, Lilo Saber, Guy and Olga Ignon, John Torsuch, Dilly and Elizabeth, Rawson Harmon, the John Wilson’s, Isabel Hermes, Richard Paige, Wallace Burr, Headmaster of O.V.S., John Perkins, Elena Green, the Jacobs and Parkers, Dean Thompson’s. And thanks to Margaret Thomas for the Building Blocks Fund.

When the prospect of adding more grades came about I went in the summer of 1948 to New York where I attended classes at Teacher’s College under the teaching of childhood education dealing with reading methods in particular and materials.

High standards in academic subjects are maintained and I think a love of inquiry and independent thinking and learning about the world was encouraged. Except for basic standardized readers put out by Scott Foresman and arithmetic tests the choice of other texts was left to the director and teachers and teachers were free to use their own educational recourses in class projects. And of course each class had its own library from which the children chose their free reading material. Harcourt was an accepted responsibility. A lot of attention was given to the phonetic help applied to spelling and reading to the children create a great deal of original creative writing. But I think what permitted the school, and for which it won its reputation for creative activities, was through music and dramatic play. A sturdy old fashioned upright piano was on the cement floor of the pergola and for years was the focal point for the daily singing classes, folk dancing, rhythm and dramatic play. These activities culminated in the Christmas celebration and the end of the year play, usually a script written from a well known children’s classic, was performed to an audience of parents and friends of the school. I have never regretted having put so much emphasis on these musical and creative subjects and all the related skills for from it was the heart of the school. I have always maintained that a school environment needs music and that children’s responses are self-evident of the beneficial effect of music and its therapeutic or pure enjoyment in the ability to sing songs together, more freely and enjoy dancing and have the fun of acting out a part.

This deep rooted feeling for children have a well grounded, sensitive and appropriate beginning in learning musical instruments, however elementary would give a student confidence and pleasure in making music. My desire is to present children with musical experiences at an early age that allowed for a child as well in studying an instrument. In conjunction with the respective music teaches them and where music education was given an important place in the curriculum. This interest in “right beginnings” was carried over much later when the Monica Ros School was founded and where an emphasis was given to an environment that allowed for a children’s creativity and growth, learning and happiness.

Naturally one would hope that the school may continue with the same emphasis, however differently expressed, but always with sensitive and discerning concern for quality and cultural enrichment.

This then is a summary of those early years of what I feel was the life of the Monica Ros School in its simple environment, dedicated to the children’s “right beginnings” in learning and living, not in an authorative lest a “harmonious atmosphere”which was how a former teacher expressed her feelings to me.

FEELINGS BETWEEN SCHOOLS

The Ojai Valley is a notable friendly place, I believe. I have always found a good feeling between schools of different types and a spirit of helpfulness. To name instances in our case. The principal of the grammar school is the most wonderful about allowing children from my school to ride the school bus to various school activities, generally dramatizations, and extra chairs will always be willingly loaned out. The exchanging and lending out of costumes for plays, which resulted in a teacher and some boys from the Thacher school (for High School Age) caring they came to photograph the children in their Alice in Wonderland costumes for free. And then is constant introduction of applications for this or that teaching positions between schools.

DESCRIPTION OF THE COMMUNITY IN OJAI VALLEY

The community of Ojai Valley has varied interests but certainly the main ones are orange growing and schools. In between people are interested in small businesses, artistic treats, music, painting, ceramics, and acting. Then there are the philosophical minded and church minded. Also a certain fluctuation among people from the east who have found Ojai a desirable place to have a winter home (and put their children in school) who have contributed to cultural standards.

My policy has always been and has been carried into effect that school fees should be within the means of the lower bracket income groups. I can safely say that children are enrolled from every varied walls of life and there is no disturbance of race, creed, colour or any difficulties about it.

TEACHING: Not by method but by a process of renewal

A bigger me. what kind? In California we deal in superlatives: theirs are apt to be the biggest and the best. When someone asked what kind of an instrument a double _____(?) was, he was told that it was a California violin. A bigger me in relation to teaching should have another meaning, another dimension surely? Are we bigger in size of importance or in understanding? Understanding we hope – at least it is an illusive attribute to describe.

In teaching very young children what does understanding employ? Warmth, humor, values, training, experience, calmness, intelligent guidance — there are endless attributes for an understanding teacher. If one were to divide these attributes into two categories we should have the thinking ones and the feeling ones. Together they could create a well balanced person. I think a real state of awareness, of understanding comes about if a person has a balance of thought and feeling no matter at what level. Obviously there is no pattern for this, but it does seem desirable that a teacher be a balanced thinking feeling person. Fundamentally is there wrong and right? What we do today will be regarded as wrong tomorrow? What is it than that we seek to do? Teach in the right way surely! We’d make a method out of new ideas! No, the direction I see is for an awareness of the present and constant re-creation of values. Children live in the moment – they should be our cue.

The distinction however, is not between order and disorder. To think that mechanical teaching is orderly whereas developmental teaching is chaotic, is a very great mistake. All good teaching is orderly, but there are different kinds of orderliness. The moment some people see any order sequence of work they are inclined to call it mechanistic. Nine times out of ten they are right, but they are guessing just the same. One must look deeper. One must find out whether it is externalistic and whether in practice it emphases accumulation, for these are the decisive features of the mechanicistic approach. There are _____(?) arguments against mechanistic teaching. It does not work out well in practice and it is based on a false psychology.

The young beginner has the same kind of quality of experience as the highly developed expert, the only difference lay in degree.

It is a very strange thing how often both the friends and foes of developmental teaching fail to realize its essentially orderly character, how often they seem to take it as the equivalent of chaos.

Music is my other assignment and this I dwell upon lovingly because of the enrichment and values it gives to children’s lives as perhaps no other subject can do in these early grades, provided there is a sensitive approach as in everything else. It opens up an opportunity, new vistas for the creative imagination of the child, it accents feelings, nurtures the natural artistic responses. This therapeutic value and gives endless delight and fun. Children’s responses to music delight one as much as rewarding conversations or certain stories. Dr. Mus____(?) has _____(?) out.

PERSONAL REASONS FOR DECIDING TO TEACH OTHER THAN FINANCIAL

What makes people want to become teachers? I can only answer for myself. Things, small things seemingly at the time stand out clearly and have obviously given direction to my interests. Happenings that have not been blurred from memory because of their long range significance. Once in my early teens I remember not being able to control tears because a very young child, who was sitting in a school assembly hall, affected me just by the appearance in her face. Another time I was conscious of a clear cut resolution, often having suffered at hand of bad violin instructors with bad temper _____(?) and suddenly finding haven in discovering I could do this with another type of teacher — to be a good music teacher of children because it was important.

GROWTH OF SCHOOL

The Ojai Nursery School and Kindergarten (now with an addition of first and second grades) began from a group of five children who came to me first for music and rhythmic play and by request of the parents was later formed into a Nursery School group. School was held in the veranda round a central patio and garden with some basic equipment installed. In the succeeding six years a kindergarten was added and a subdivision made of the four year olds, a first grade and next year a second grade will be added. So that children are enrolled here from years of 2 to 7 years. Also there was a remodel to a permanent residence where once again house and grounds have undergone a gradual adaptation to growing needs. The physical appearance of the a school does not look like a sample designed for the specific needs of such a school age group. Where in many have a certain uniqueness, but accommodating handicaps. But at least imaginative creative ideas have been put to the test. In So. Cal children live largely out of doors — it is this normal environment and so the psychology is a different one to that of a school in a city or in a cold climate. There is no desire on my part for a large school in the contrary, but it should be large enough to have companionship and interest for children of any age group and to avoid any taint of inclusiveness. The school numbered almost fifty children last year and it is my wish not to go beyond that number or beyond a second grade like ____(?) one searches for a ______(?)

CONCLUSION

In the beginning I can only say that I hope the intent of the little school spoke for itself through the responses of the children as they felt physically secure when they first made a break from home and continued to respond and flower as they entered kindergarten and Grade school.

I hope this has given an account of the school and its atmosphere, its problems and its aspirations. The school problems are my problems. I do not know any other method than to go about then in a spirit of constant deciding – even renewing ones ideas and this does not imply uncertainty, on the contrary it is an understood, logical process. If traditional education is wrong and progressive education right, why aren’t more educational problems part of the whole school. A new experience for me will be teaching second grade and also having two age groups at one time.

I find myself in charge of a school of my own which has grown far beyond what at first contemplated and with insufficient training for the job that it has developed into. I can draw on my music training and teaching, travel and philosophical background and an early childhood of _____(?) simple growth but in a cultural _____(?) home environment and school largely with a generous or small groups. But it is naturally not enough, I feel in an insecure position from the fact of holding no degree. I have taken courses wherever possible and will continue to do so. While I attained certain results with the children and parents have been satisfied I am greatly indebted to the direction of _____(?) such work that is given at Teacher’s College and hope I am able to work with the children _____(?) times of none _____(?) and valuable experiences there.

(AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NOTES CONTINUE)

Now we go back in time a little. It was in 1925 or 1926 Margaret and I left our home in Roseville to live in a community of people where there were numbers of young people, often with their parents, who were members of the Theosophical Society. Our mother had been a member for years. There was no coercion as far as we were concerned, but eventually we joined the society, too, for we had many friends there. For someone like my mother it was a broadening influence from the accepted conformist church doctrines. In this community there was a definite dedication to training and study of theosophical doctrine and thought, but otherwise everyone was free to pursue his or her respective manner of living a livelihood if necessary. I continued with my associations at the Conservatorium and did some teaching and had a job in a radio station for a musical programme and Margaret worked in town for some firm. For some personal reason Margaret never wished to discuss this period in her life; she seemed embarrassed to tell anyone about it – it was hard to explain I suppose, though the Theosophical Society was and still is a recognized liberal mode of religious thought by many people all around the world. Anyway, our connection with it was a fact and I leave it to you whether it seems appropriate to mention it or not. I know Margaret really rejected it. She said once — Those dotty times. I think the difficulty arose in trying to explain this period of her life to others. While personally not in the least interested now, I look upon this period as a broadening experience. One did meet people in Sydney from all parts of the world too. I for one my husband who was a Theosophist from Havana, Cuba and visiting the center, as it was called, in Sydney. Margaret had an invitation to visit friends in Holland, which she did, and then made her way to London alone. We, of course stayed on in Ojai where I have had my home ever since.

Margaret never told me much, but I think it was a frightening experience for her to be alone in London, very little money and tramping about with her portfolio of drawings and letters of introduction and references from Sydney. As I mentioned before we were so unsophisticated. I’m sure we had never been in a hotel. Those must have been grim times for Margaret. I know father helped out, but Margaret was so independent. Father died in July of that year, 1929. Mother and Pat came over to London to be with Margaret in 1930. They lived in St. Johns Wood, Margaret working and Pat studying, singing and ballet. Florence James perhaps can tell you about those times and what Margaret did to make her way. I have no letter to refer to having unfortunately destroyed all mothers of that time. In 1933, mother decided to go back to Sydney leaving the girls in London. As her health was not good and mother felt the climate too severe in London, but in February of that year she died at sea on the voyage out.

In 1937, I was able to take a short trip to visit my sisters while my husband went to Havana. Margaret was married happily to Arthur Freeman then they had a top flat in an apartment in Inglewood Road, Hampstead which Margaret, with her usual flair, made very attractive and I thought even the view of chimney pots enchanting. Florence James perhaps can tell you more than I about those times and what Margaret did in the way of making her way. I have no letters to refer to. I took a bus tour and enjoyed all kinds of theaters and trips to Scotland but feel a visit from a sister from So. Cal. was a bit of a strain. Pat was living somewhere else and well into the musical opera touring business. Arthur, of course could tell you what they actually did then. I can remember Margaret working at sketches in the flat.

Soon after my return to California World War II in 1939 began. That was a terrible time. Margaret’s letters were gay and funny as usual describing events, which must have been petrifying in reality. I managed to speak by phone once. Of course the U.S.A. did not enter the war until much later 1945.

As I have written earlier after my return from a visit to Havana in 1940, I resumed teaching music. Formerly I had taught violin in particular when my husband was alive, and as I mentioned I later formed a class of nursery school age children for musical experiences of all kinds, which developed into a Nursery School later. In 1944 I was able to purchase a property near by which was ideal for a little school and which on the same site is the Monica Ros School though I retired as director sixteen or more years ago. Margaret on the other hand had a keen insight into children’s minds and needs and ways, but strangely contended she did not like them about personally. So we had different ways of expressing our feelings toward children. I devoted to teaching, she as an illustrator. I included a brochure for which Margaret supplied the drawings. She would sometimes at my request send me illustrations for costumes, which I needed when the school was involved in a period play performing plays for was a high light of the schools curriculum including music of all types.

In 1955 I paid a short visit to Sydney and stayed near the Freeman’s at Elizabeth Bay. They had returned from London in 1949 and were making their way, Margaret in her chosen field as an illustrator of children’s books and Arthur was teaching at the Technical College. I retired from the school in 1968 and in 1969 I returned again to London for six months after my retirement. Margaret and Arthur then lived near the Hawkesbury district and Margaret was then hoping then to conclude her work as an illustrator of children’s books for I recall the effort it was for her to get assignments finished. Soon afterwards they sold up everything and went to live abroad mainly in Mallorca until their return to Sydney where Margaret became increasingly frail and died in September 1978 after months of a sad coma like existence.