Sharp & Savvy: Charles Millard Pratt (1855 – 1935)

by David Mason

Mr. Pratt was born in Brooklyn, New York on November 2, 1855. His father, Charles Pratt Sr. was, at the time, the richest man in Brooklyn and was a partner in the Standard Oil Company with John D. Rockefeller.

By 1879, Charles M. Pratt had graduated from Amherst College and had received an honorary M. A. from Yale, before joining his father’s company, Standard Oil as the company secretary. At various times he was also president and a director of the oil company.

In 1884, he married Mary Seymour Morris, the daughter of the Governor of Connecticut Luzon B. Morris. The Pratt’s had five children.

Mr. Pratt was appointed as a trustee of Amherst College, his alma mater and Vassar College, his wife’s alma mater. He became president of the board of trustees for the Pratt Institute  in New York.

He served on the boards of the Long Island Railroad, and the Brooklyn City Railroad. He was a director in the American Express Company, the Mechanics and Metals National Bank and the Union Mortgage Company.

His interests varied as he was also a director in the Pratt and Lambert Paint Company, the Self Winding Clock Company, and the Chelsea Fiber Mills.

Mr. Pratt was the first alumnus to donate a building to Amherst College, the Pratt Gymnasium, erected in 1883.

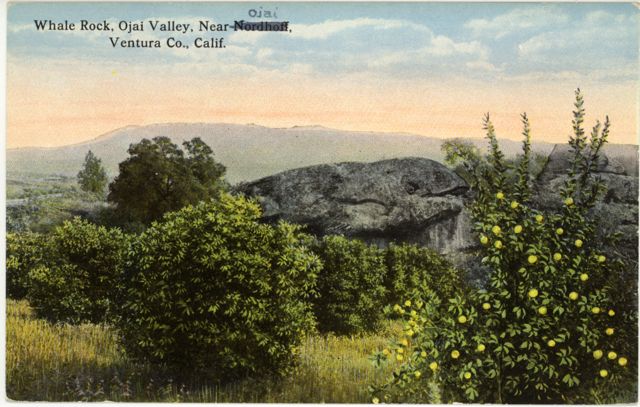

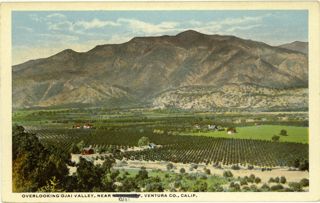

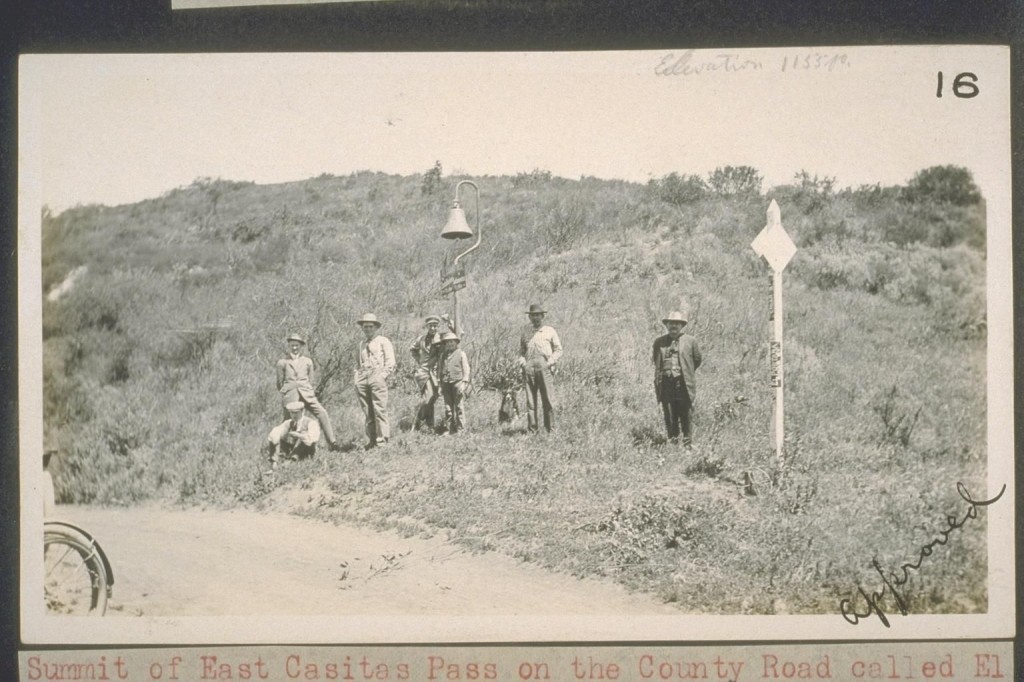

Discovering Ojai, Mr. and Mrs. Pratt purchased acreage just north of the Foothills Hotel with thoughts of building a winter home here.

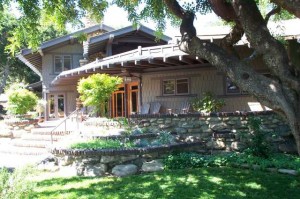

Their choice of architects was the popular Greene and Greene bothers. Many glowing articles were being written about the Greenes, and the Pratts decided that they should have them design their new home.

The Greene brothers placed less emphasis on a formal entry and spacious living and dining areas. Instead, the entry door opened directly into the modest living room. Despite the informality, however, all details of the Pratt house design were given the Greenes’ strict attention. Mr. Pratt was a shareholder in the Foothills Hotel and, consequently, they entertained at the hotel rather than at home.

In 1916, with the Nordhoff High School in need of additional classrooms, Mr. Pratt donated the money to build two very important buildings for the school. One was for manual training and the other for domestic science and art. These additions to the school cost Mr. Pratt $25,000. In 1917, when the forest fire swept through the valley, the manual training building was burned and Mr. Pratt had it replaced immediately.*

Charles Millard Pratt became an invalid and bedridden in 1925 and spent the rest of his life at the family estate in Glen Cove, Long Island. His important contributions to the Ojai Valley had come to an end. He died in November of 1935.

The Pratt House is a Ventura County Historical Landmark and a Federal Landmark. For all times this building has been one of the Greene and Greene brothers’ masterpieces.

*As a tribute to Pratt, the 1916 Nordhoff Yearbook included the following poem:

Charles Millard Pratt

To the man from out of the East

Who bears choice gifts

To bless us and those who follow,

Gifts of gold, but also

Gifts of character and the spirit

Of plain democracy,

More enduring,

We dedicate this, our annual.

1916Â Nordhoff Topa Topa Annual