When Britain’s legendary Satire Boom took off in the early 1960s, Ojai’s Peter Bellwood was right in the thick of it, hopping on one leg.

(From The Ojai Quarterly, Spring 2018)

By Mark Lewis

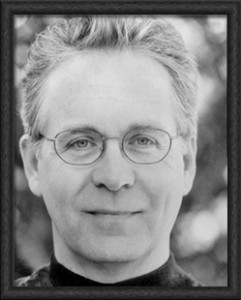

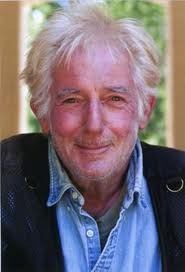

MANY people in Ojai are fans of the popular Netflix series “The Crown,” but few feel a personal connection to its subject matter. We’re contemporary Americans, watching a historical drama set in Britain the middle of the last century – a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. But for the Brits in our midst, the series hits rather closer to home. Especially if, like Peter Bellwood, they spot some old friends among the characters on the screen.

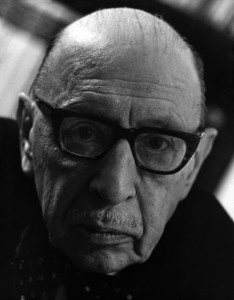

Bellwood, an Englishman born in 1939, has never met Queen Elizabeth II, the lady who wears the crown in question. Nor did he ever meet the late Harold Macmillan, whose term as prime minister from 1957 to 1963 provides the setting for Season 2 of the series. But there’s a key scene in the season finale where Macmillan visits London’s Fortune Theatre to see a satirical revue called “Beyond The Fringe,” featuring four young men in gray suits. In real life, Bellwood knew the four performers well – especially Dudley Moore, who is shown seated at a piano, and Peter Cook, who is shown humiliating Macmillan with a deft and mercilessly phrased ad-lib.

Bellwood was not in the Fortune Theatre that night, but he was living in London at the time, and Cook soon would invite him to join the cast of another satiric revue, “The Establishment,” a major link in the chain from “Beyond The Fringe” to “Monty Python’s Flying Circus.” That was the beginning of Bellwood’s professional career in show business, which later brought him to Hollywood as a screenwriter, and eventually to Ojai, where his satirical columns enliven the pages of The Ojai Quarterly. But his connection to Cook actually went back several years before “Beyond the Fringe,” to his undergraduate days at Cambridge University — when the Satire Boom was still a squib, and Bellwood was present at the creation.

A YORKSHIRE LAD

Peter Bellwood was born and raised in York, where he attended St. Peter’s, a private school of ancient lineage where past alumni included the infamous Guy Fawkes, who tried to blow up Parliament in 1605. (It seems that Old Peterites are predisposed to booms, satiric or otherwise.) In the fall of 1958 he arrived at St. Catharine’s College at Cambridge University with a view to studying law. But fate diverted him to a different path, due to an unusual talent.

“Well, I played the ukulele,” he explains.

During his freshman year, a St. Catharine’s group called “The Midnight Howlers” put on a concert that included Bellwood with his ukulele, singing comical songs popularized by the entertainer George Formby. Adrian Slade, the president of the very prestigious Cambridge University Footlights Dramatic Club, happened to see the show, and was impressed enough that he recommended Bellwood to John Bird, who was directing the annual Footlights revue. Bird auditioned Bellwood, inducted him into the club and cast him in the show.

“It just fell out of heaven,” Bellwood says. “I was the first freshman ever invited to join.”

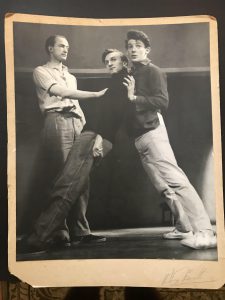

And so at a tender age he found himself among the players in “Last Laugh,” in June 1959. The revue’s other cast members included Bird; the actress Eleanor Bron; the future politician Geoffrey Pattie, who one day would serve in Margaret Thatcher’s Cabinet; and Peter Cook, who preferred tormenting prime ministers to serving under them.

“Last Laugh” was no mere run-of-the-mill college revue. The performance was recorded for a privately pressed LP (Bellwood still has his copy), and the cast was photographed by Princess Margaret’s fiancé, Antony Armstrong-Jones (whose romance with the queen’s younger sister figures prominently in Season 2 of “The Crown”).

Cook was already a legend in the making. Cambridge was grooming him to be a diplomat like his father, but diplomacy was not his forte. Everything Cook encountered became grist for his comedy. Seemingly without effort, he churned out skit after skit, and not just for the annual Footlights revues – he also was supplying material for London stage revues.

“Peter was regarded as a phenomenon,” Bellwood says, “because he was an undergraduate making West End money.”

One of Cook’s most famous skits, “One Leg Too Few,” was inspired by the sight of Bellwood standing on one leg to scratch the sole of the other foot. Instantly, Cook invented a scene in which a one-legged actor auditions for a role that would seem to require the full complement of lower limbs.

“It just came out of his mouth,” Bellwood recalls. “He said, ‘Now, Mr. Spiggott, you are auditioning, are you not, for the role of Tarzan.”

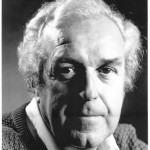

When “One Leg Too Few” was performed in the 1960 Footlights revue, “Pop Goes Mrs. Jessop,” Bellwood himself played Spiggott, hopping about on one foot. In later years the role would be associated with Dudley Moore, who in 1960 was a recent Oxford graduate and an aspiring jazz pianist. At some point that year, Bellwood and other Footlights members opened a club room in their theater building. To launch it, they threw a party that drew jazz musicians from far and wide – including Moore, who showed up with his trio.

“It was now that he met Peter Bellwood,” wrote Moore’s authorized biographer, Barbra Paskin. In her book, she quotes Bellwood recalling the party as “wildly entertaining and never ending, with a jazz concert that continued through the early hours of the morning.”

Bellwood bonded with Moore, as he already had bonded with Cook – but not with David Frost, another Cambridge undergraduate and Footlights member.

“He was a creep,” Bellwood says of Frost. “He stole all of Peter Cook’s material.”

Cook served as president of the Footlights in the 1959-60 year, then made his big leap shortly after graduation. That summer, he joined the cast of “Beyond the Fringe,” a Footlights-style revue that debuted at the annual Edinburgh International Festival on Aug. 22, 1960. (The “Fringe” in the title referred to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, an alternative arts festival that takes place each year at the same time as the more traditional festival.) The other three “Fringe” cast members were Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett and Jonathan Miller. Together with Cook, they comprised a cultural pivot point in Britain’s postwar history.

“It created an explosion,” Bellwood recalls.

So much so that in May 1961, “Beyond the Fringe” took up residency at the Fortune Theater in London’s West End, where it was such a hit that Harold Macmillan came to see it, having heard about Cook’s impersonation of him. Spotting the prime minister in the audience, Cook ad-libbed a new line, which he delivered using Macmillan’s plummy upper-crust accent:

“When I’ve a spare evening, there’s nothing I like better than to wander over to a theater and sit there listening to a group of sappy, urgent, vibrant young satirists with a stupid great grin spread over my silly old face.”

As “The Crown” would have it, Macmillan was deeply embarrassed. In real life, the PM apparently was a better sport. (Queen Elizabeth also saw “Beyond The Fringe” during its London run and she reportedly enjoyed it.)

Cook’s irreverent humor suited the times. The Suez Crisis of 1956 had stripped Britain of the illusion that it was still a first-class world power. The British had won World War II but lost their empire, and now found themselves playing second fiddle to those upstart Yanks across the pond. As a result, the traditional deference given to establishment institutions like the monarchy, and to upper-class statesmen like Macmillan, was curdling into something far less respectful.

Bellwood points out that Cook’s humor owed a great deal to the anarchic antics of Spike Milligan, Peter Sellers and others on the popular 1950s BBC radio program “The Goon Show,” which was more surreal than satirical. But in Cook’s hands, British humor acquired a political edge that had much to do with the nation’s suddenly diminished place in the world. His Macmillan impersonation called to mind an out-of-touch aristocracy in the process of passing from the scene. Hence the sting of his ad-lib at the Fortune Theatre that night.

Back at Cambridge, meanwhile, Bellwood was now a senior, and had succeeded Cook as president of the Footlights. One day he and Frost, the club secretary, were invited to a cabaret revue that featured future Monty Python stalwart Graham Chapman, who was angling for a Footlights audition.

“We gave them gallons of claret and didn’t start until they’d drunk at least a bottle each,” Chapman recalled in the book “Pythons: The Autobiography, By the Pythons.”

Whether it was the claret or his performance, Chapman did wangle the coveted invitation from Bellwood and Frost to audition. So did John Cleese, another future Python.

“I impersonated a carrot and a man with iron fingertips being pulled offstage by an enormous magnet,” Chapman recalled. “In the same set of auditions John Cleese did a routine of trampling on hamsters, and can still do a good pain-ridden shriek. We were both selected and very soon were able to wear black taffeta sashes with Ars est celera artum (the art is to conceal the art) on them.”

Bellwood by this point had switched from law to history but was devoting most of his time to the Footlights and to having fun, to the point where he was in danger of being sent down before he graduated. But the head of his college noted that Bellwood was the first St. Catharine’s undergraduate to serve as president of the Footlights, which constituted a feather in the college cap. So he was allowed to graduate with his history degree in 1961.

Going up to London, he found a flat in Notting Hill and a job in advertising, producing TV commercials for laundry soap. His flat-mates included his old Footlights comrades John Bird and John Fortune, who were now performing on a London stage. Bellwood soon moved to grander digs on Prince of Wales Drive in Battersea, which he shared with Peter Cook and others.

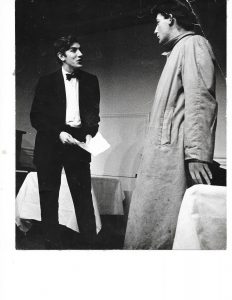

The success of “Beyond the Fringe” prompted Cook and another old Cambridge pal, Nicholas Luard, to found The Establishment, a nightclub on Greek Street in Soho. The main stage featured Bird, Fortune, Eleanor Bron and Jeremy Geidt performing a “Fringe” style satirical revue, while the basement stage featured jazz musicians. (In this article, “The Establishment,” within quotation marks, refers to the revue; The Establishment, without quotation marks, refers to the nightclub.)

A new world was stirring. Cook & Co. came into their own during the early ‘60s, “between the end of the Chatterley ban and the Beatles’ first LP.” The Satire Boom was now in full swing, and not just on the stage. There was also a new satirical magazine, Private Eye, and a new TV show, “That Was The Week That Was,” hosted by David Frost. And everyone who was anyone hung out at The Establishment – including the “Fringe” cast members, who came to the club after concluding their evening performance at the Fortune Theatre. Greek Street was jammed nightly with club-goers hoping to rub elbows with hip young movie stars like Michael Caine and current Ojai resident Terence Stamp, or with the supermodel Jean Shrimpton. Celebrities and would-be celebrities alike crowded into the club to be part of the scene.

“They all came to The Establishment,” Bellwood says. “They all wanted to be seen and be written about in the society columns.”

“Beyond The Fringe” moved on to America in the fall of 1962 with its four original cast members, who scored a big hit on Broadway. Building on this success, Peter Cook decided to replicate his London nightclub success in New York. He acquired the original site of the storied El Morocco nightclub on East 54th Street, lately converted into an imitation English music hall called The Strollers Theatre Club. Cook then summoned the original “Establishment” cast – Bird, Fortune, Bron and Geidt – and installed them in The Strollers. They were a hit, giving Cook two simultaneous hit shows in New York, but also giving him a problem: He needed to recruit a replacement “Establishment” cast for his original club back in London.

“Peter called me from New York,” Bellwood says. “And I said yes.”

This was a pivotal point in Bellwood’s life. He was 24, and making good money in advertising. Did he really want to chuck it, and commit himself to the vagaries of a show-business career? Indeed he did. Performing at The Establishment offered all the fun of being in a Footlights revue while also getting paid for it, and winning applause from the great and the good of Swinging London.

“I thought I’d died and gone to heaven,” Bellwood says.

And so Peter Bellwood stopped selling soap and became a professional entertainer – and soon a journalist as well, when he agreed to write for Nicholas Luard’s new Scene magazine. His first assignment involved a different sort of satirist: Lenny Bruce.

GET HIM TO GREEK STREET

Bruce had come to London to play The Establishment in 1962, and was booked for a return engagement in April 1963.

“I loved him,” Bellwood says. “A very sweet, charming guy.”

Bruce was less sweet on stage. He was famous – or infamous – for “sick humor,” foul language, and his heroin habit, which led to frequent arrests. His satire was much harsher than Cook’s.

“He went after sacred cows without caring whether he was upsetting people or hurting their feelings,” Bellwood says. “Whereas Cook wasn’t going for the jugular, he was just making fun of things and people. While Bruce may have been savage in his satirical take on the world around him, Cook was really very benign.”

Bruce had made quite an impression on his previous London visit, so much so that when he returned, the Home secretary ordered him deported back to New York as an undesirable alien. As it happened, Cook was attending a dinner party that evening at the Manhattan home of Joseph Heller, the celebrated author of Catch-22. But Cook ended up spending the entire evening on the phone to London, hatching a scheme to get Bruce back into Britain via a back-door arrangement. He had Bruce fly from New York to Dublin, where he was met by Bellwood, whose assignment was to get Bruce back to London by hook or by crook, and then write up the entire saga for Luard’s magazine. Inevitably, given Bruce’s notoriety, this escapade became international news.

“Mr. Bruce was met in Dublin yesterday by Peter Bellwood, a writer and performer at The Establishment,” The New York Times reported. “Early today they hired a car and drove across the border at Belfast.”

Cook’s idea was to exploit a loophole in British law that made it easier to enter the country by crossing the border from Ireland to Northern Ireland. Alas, the scheme failed. When Bellwood and Bruce arrived in London, the authorities deported the controversial comedian back to New York for the second time in a week. He never did play that return engagement at The Establishment. But at least Bellwood had a good story to write up for Scene.

CROSSING THE POND

Six months later, Bellwood boarded his own flight to New York. Peter Cook, ever the Satire Boom impresario, had sent the original “Establishment” cast on tour and imported a new cast, including Bellwood, to hold down the fort at the Strollers Club on East 54th Street. Cook got Bellwood a room at the legendary Chelsea Hotel on West 23rd Street, a Bohemian establishment well stocked with colorful characters, many of them artists. (The writers James G. Farrell and Brendan Behan were among those in residence at the time.) From there it was a short subway ride uptown to the Strollers, where Bellwood made his New York debut on Oct. 31, 1963.

“A new troupe took over ‘The Establishment’ last night,” the New York Times announced. “Peter Bellwood does fine as a straight type who tells the sad tale of how heterosexuality brought his downfall.”

Cook still was starring in “Beyond The Fringe” on Broadway with the other members of the original cast. Late in its New York run, they revamped the show by adding new sketches, including one that actually was an old sketch: “One Leg Too Few,” which Cook and Bellwood had performed together while at Cambridge. Now it was Cook and Dudley Moore who paired up for the skit, with Moore portraying Mr. Spiggott, the one-legged actor who wants to play Tarzan.

“This pairing was very much the beginning of the Cook-Moore partnership that went on to dominate British comedy throughout the rest of the Sixties,” Cook’s biographer Harry Thompson would write.

The original Spiggott, Bellwood, continued to appear in “The Establishment,” and to enjoy life in New York. After concluding their respective evening performances, the casts of both British satire revues would hang out together, often convening at Barbetta, an Italian eatery on Restaurant Row, west of the theater district. Right across the street was the famous Broadway hangout Joe Allen, where Bellwood met his future first wife, Pamela, in the bar.

When Cook married his own first wife, Wendy Snowden, in a Greenwich Village chapel in October 1963, all the up-and-coming young Brits in New York were there, some already famous, some soon to be. Dudley Moore played the organ, and Bellwood served as best man.

“The two Peters, handsome and dashing, were like magnets drawing me up the aisle,” the bride recalled in a book. At the reception, she wrote, “Peter Bellwood was witty too and made up all sorts of stories about Peter’s and my childhood and our time in Cambridge.”

Peter Cook returned the favor a few years later, standing up for Bellwood when he married Pamela. Bellwood recalls Cook’s typically irreverent approach to his best-man duties: “He leaned into my ear and said, ‘Are you sure you know what you’re doing?’ ”

Bellwood grew close to Dudley Moore during these New York years, in part because they both enjoyed socializing with jazz musicians like Paul Desmond, whose alto-sax solo on “Take Five” by The Dave Brubeck Quartet remains one of the defining melodies of the early ‘60s. But music was changing, a point driven home to Bellwood one evening when he and Desmond walked past the Warwick Hotel and found it besieged by screaming teenage girls. It seems that the casts of “Beyond the Fringe” and “The Establishment” were no longer the most popular British performers in New York. A new quartet from England was staying at the Warwick. Their names were John, Paul, George and Ringo.

“I remember seeing Ringo waving to the crowd from a hotel window,” Bellwood says.

Back in Britain, the Satire Boom was running out of steam. But in America, British comedy was bigger than ever, thanks to the Beatles. The Fab Four arrived New York in February 1964 for their epochal “Ed Sullivan Show” appearance, and from their first press conference it was clear that their appeal was not limited to their music. They were funny, and in a way that seemed utterly fresh to Americans, few of who had ever heard “The Goon Show” or seen “Beyond The Fringe.” It was the Beatles’ humor and charm that made their first film, “A Hard Day’s Night,” such an enormous hit.

The British Invasion was in flood tide, and Bellwood was along for the ride. After “Beyond The Fringe” and “The Establishment” ended their New York runs in the spring of 1964, Cook and the others went home to London. Bellwood remained. He was already home.

“I’d always wanted to be here, in America,” he says. “I wanted to stay.”

IMPRESARIO

Deciding that he wanted to be a producer rather than a performer, Bellwood joined the Establishment Theater Co., which Cook had created with the stage producer Ivor David Balding and the independent film producer Joseph E. Levine. The actress Sybil Burton (recently divorced from Richard) signed on as artistic adviser. The idea was to import cutting-edge plays from London and produce them at a new off-Broadway theater that Cook had built right above the Strollers on the same site. (He christened it, with stunning originality, the New Theater.) To helm the new venue’s first production, Balding and Bellwood lined up the hottest young theater director in New York.

“We did ‘The Knack,’ with Mike Nichols directing,” Bellwood says.

“The Knack,” by Ann Jellicoe, was an import from London that opened in the New Theater on May 27, 1964, and became a major success, making a star of George Segal. The Establishment Co. next imported “Serjeant Musgrave’s Dance” by John Arden, which failed to make a star of Dustin Hoffman because the then-little-known actor was fired during rehearsals. (This play did, however, boost the career of another cast member, the young Roy Scheider.)

Meanwhile, downstairs from the theater, in the space formerly occupied by the Strollers and before that El Morocco, Sybil Burton created New York’s first discotheque. Its name was suggested by Mike Nichols, inspired by the scene in “A Hard day’s Night” in which a supercilious journalist queries George Harrison about his mop top.

“What would you call that hairstyle you’re wearing?”

“Arthur,” Harrison replies, in the anarchic “Goon Show” spirit.

Arthur, the disco, was phenomenally popular. As with The Establishment club in London three years earlier, everyone in New York flocked to East 54th Street to be part of the new scene. Arthur was the hardest club in town to get into, yet Bellwood was a regular, hanging out there with the likes of Nichols and the English film star Rita Tushingham. Bellwood had only been in New York for a year, but he most definitely had arrived, and he was rubbing elbows with the right people. People associated with the Establishment Theater Co. were going places, and they helped each other out. Case in point: Joseph E. Levine hired Nichols to direct the film “The Graduate,” and Nichols cast Hoffman as the lead.

Bellwood’s own dream project involved making a film out of Bruce Jay Friedman’s novel “Stern.” He acquired the movie rights, offered Alan Arkin the title role, and approached Richard Lester to direct it and Terry Southern to write the screenplay. Everybody said yes except Southern, so Bellwood wrote the screenplay himself, and started shopping the project around to the money men.

He had not completely turned his back on performing. Periodically he went out on short tours with “The Establishment.” One such venture loomed in the summer of 1965 – but only three former “Establishment” players were available, so the tour’s producer began casting around for another Brit with satire chops who could fill the fourth slot. The pickings were slim, apparently, but finally the producer heard about an actor who might be suitable.

AND NOW FOR SOMEONE COMPLETELY DIFFERENT

John Cleese had caught the tail end of the boom in Britain when he co-wrote and starred in the 1963 Footlights revue, “A Clump Of Plinths.” A hotshot London producer renamed it “Cambridge Circus” and transferred its cast to a West End theater, where Graham Chapman joined the lineup. A year later the show landed on Broadway for a short run. After it closed, Chapman went back to London, but Cleese stayed on in New York. He appeared in a Broadway musical, “Half A Sixpence,” and then he gave journalism a go, hiring on at Newsweek. That did not work out well, and Cleese quit before he was fired.

Rather than go back to performing, Cleese decided to find himself a serious job, perhaps in a bank or an advertising agency. But before he could follow through on that decision, he had lunch with the above-referenced producer, who offered him the fourth “Establishment” slot. Having just renounced show business a few days earlier, Cleese was all set to decline the offer, until he found out who else would be in the cast.

“The group of four included Peter Bellwood, who had been president of the Footlights in my first year at Cambridge, and who was an immensely likeable and amusing fellow,” Cleese wrote in his autobiography. “I knew it would be a pleasure to work with him, so I said ‘yes’ over the coffee, and agreed to start rehearsing the very next day.”

This production of “The Establishment” was a mini-tour with two stops, Chicago and Washington. It opened in July 1965 in a small theater in Hyde Park, near the University of Chicago. Inevitably, the sketches included one that lampooned Queen Elizabeth.

The Queen: “Philip, what is an anachronism?”

Bellwood, as Prince Philip: “You’ve been reading again, haven’t you.”

The show was such a hit that it was held over for a week and attracted the attention of the novelist Saul Bellow, who lived in Hyde Park.

“I had just finished reading “Henderson The Rain King,” recalls Bellwood, who was nonplussed when the book’s famous author came backstage before the performance to meet the “Establishment” cast.

“I heard you guys are funny,” Bellow said.

When the show was over, Bellwood recalls, the novelist came backstage again to deliver his verdict: “He shook all of our hands and said, ‘You guys are funny.’ ”

Bellow was not the only one who thought so.

“The critics were surprisingly enthusiastic about our performances, too, singling out Peter Bellwood in particular,” Cleese wrote. “He had a very engaging, relaxed style, with a wry affability that concealed his precision.”

Bellwood returns the compliment, describing Cleese as “one of the funniest men, after Cook, I’ve ever known.”

Cleese enjoyed this “Establishment” tour so much that he never followed through on his decision to leave show business. When the tour ended, he went back to London and accepted an offer from David Frost to join the cast of a new BBC TV show, “The Frost Report.” That show reunited him with Graham Chapman, who was one of the writers; the others included Eric Idle, Terry Jones and Michael Palin. These five, plus the American Terry Gilliam, would go on to create “Monty Python’s Flying Circus.”

Here is irony. It was the prospect of working with Bellwood that had induced Cleese to do the mini-tour, the success of which prompted him to continue as a performer, which in turn led him to “The Frost Report,” which led directly to “Monty Python.” Yet Bellwood, despite his excellent notices, made the opposite decision: After the mini-tour ended, he turned away from performing to focus on producing “Stern.” Unfortunately, he never managed to get the project funded.

“I came close, but it didn’t happen,” he says.

But the script he wrote for it impressed Arkin, who showed it to his agent, who offered to represent Bellwood as a screenwriter. Bellwood landed a job co-writing “Annie: The Women in the Life of a Man,” a TV special that was to star Anne Bancroft and a long list of Hollywood luminaries. Meanwhile, he also was writing the book for a star-studded Broadway musical, “Gantry,” based on the Sinclair Lewis novel Elmer Gantry, with Robert Shaw and Rita Moreno as the leads.

That was the week that was: “Gantry,” after playing four weeks of previews, officially opened and closed on Valentine’s Day 1970. Four days later, “Annie” aired on CBS and was a success, eventually earning Bellwood an Emmy as co-writer. And so in 1971 he left Broadway behind, and went out to Hollywood to do a rewrite job on someone else’s screenplay.

“The film was never made,” he says, “but it got me going as a screenwriter.”

And that, to cut to the chase, is how Peter Bellwood gave up performing and producing for writing, the trade he still plies today.

ROLL THE CREDITS

During the course of his long Hollywood career, he co-wrote the film “Highlander,” an enduring cult classic. His current project is “Monster Butler,” which is to feature his friend Malcolm McDowell, who has lived in Ojai even longer than Bellwood has. (McDowell will also serve as the film’s producer.)

Peter and his wife Sarah (also a screenwriter, and a cartoonist to boot) moved to Ojai from L.A. in 1992 to raise their daughter, Lucy, in these bucolic surroundings. (These days Lucy is a self-described “professional adventure cartoonist” based in Portland, Ore., where she creates comics and graphic novels.)

Once settled in Ojai, Bellwood resumed performing, mostly in his adopted hometown and mostly for the fun of it. As an actor, he has trod the boards at Libbey Bowl, the Art Center Theater and other local stages. As a singer and ukulele player, he performs with the popular Household Gods group. As a raconteur, he is in demand as a master of ceremonies for local charitable events. As a visual artist, he shows his vibrant collage work in local venues. As a journalist, his column, “The Bellwood Chronicles,” has been an Ojai Quarterly mainstay since the magazine’s 2010 debut.

WAIT, WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE SATIRE BOOM?

The movement’s brighter lights kept working in comedy after the boom petered out circa 1964, and they enjoyed considerable long-term success, especially in Britain, where Peter Cook and Dudley Moore worked together as a duo for many years. They returned to Broadway in triumph in 1973 with their two-man show “Good Evening.” Later in the ’70s, Moore moved to Hollywood to act in comedies such as “10” and “Arthur.”

“Dudley became a star,” Bellwood says. “Peter was very jealous of this, although he never admitted it.”

Cook was tall, handsome, charismatic, and a prodigiously talented comedian. But he could not credibly deliver lines written by anyone other than himself, and he preferred ad-libbing to following a script.

“He wanted to be a star,” Bellwood says. “He wanted to be Cary Grant. But he was not an actor. He was an improviser.”

Cook succumbed to alcoholism-related illnesses in 1995, at the age of 57. Moore also suffered from substance abuse and died relatively young, at 66, in 2002. Bellwood remained friends with both men until their deaths.

David Frost moved on from satire to forge a long and successful career as a TV interviewer, living long enough to see himself immortalized on stage and screen in “Frost/Nixon,” and to accept a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth. He died of a heart attack at the age of 74 in 2013, while traveling on a cruise ship named for the queen.

“Monty Python,” of course, became an international phenomenon as a TV show, a film franchise, and eventually a Broadway musical. John Cleese went on to co-create at least two more classics – “Fawlty Towers” on television and “A Fish Called Wanda” in films. He lived in Santa Barbara for many years, until an expensive divorce forced him to sell his beachfront mansion in Montecito, whereupon he moved back to England.

Most of the hip young satirists of the 1957-1963 period are now rather long in the tooth, if still above ground. But their former target, the queen, is still going strong in Buckingham Palace at the age of 91, as is her curmudgeonly consort, Prince Philip, age 96. Helen Mirren won a best-actress Oscar several years ago for playing Elizabeth in “The Queen,” and Claire Foy garnered honors for playing her in “The Crown,” but neither “Queen” nor “Crown” is satire. They take Elizabeth seriously and portray her respectfully.

We’ll give the last word to Peter Cook’s favorite target, Harold Macmillan. When Frost’s “That Was The Week That Was” debuted on the BBC, the minister in charge of broadcasting took offense at its satire and threatened to take it off the air. The prime minister told him to leave it alone.

“It is a good thing to be laughed at,” Macmillan said. “It is better than to be ignored.”