By Mark Lewis

Ojai prides itself on its small-town charm, but it is not so small that everyone actually knows everyone. A person can live here for three decades — as Gene Lees did — without being widely recognized. So when Lees died in April 2010 at the age of 82, his friends mourned, and his Foothill Road neighbors took note, but his passing was not big news in his adopted hometown. The Ojai Valley News did not run an obituary.

Elsewhere, it was a different story. The New York Times hailed Lees as “a prolific jazz critic and historian who approached his subject with a journalist’s vigor and an insider’s understanding.” The Washington Post eulogized him as “a multi-talented writer who left a lasting mark on jazz as a biographer, an opinionated critic, and graceful song lyricist.” The Los Angeles Times quoted former New Yorker Editor Robert Gottlieb, who described Lees as “a strong presence in jazz.”

All the obituaries dutifully reported that Lees had died “in Ojai, Calif.” None explained how it was that a legendary jazz writer had ended up in this bucolic valley, so far from the big-city clubs where his favorite musicians plied their trade. A hint can be found in Lees’s most famous lyric, even though he wrote it years before he first set eyes on Ojai.

EUGENE Frederick John Lees was born in Hamilton, Ontario, on February 8, 1928. As a young man he dreamed of becoming a painter. Instead he went into journalism, first in Canada and later in Kentucky, where he served as a music critic for the Louisville Times. By 1959 he was in Chicago, editing the jazz magazine Down Beat.

After leaving Down Beat in 1961, Lees volunteered to tag along with the Paul Winter Sextet on a State Department-sponsored tour of South America. Lees was intrigued by what he had heard of bossa nova music, and he wanted to trace it to its source. When the tour reached Rio de Janeiro, he contacted the songwriter Antonio Carlos Jobim, and they quickly became friends. On the bus trip from Rio to the tour’s next stop, Lees jotted down some English-language lyrics for Jobim’s “Corcovado.” (The original lyrics, of course, are in Portuguese.) This is how the Lees version begins:

Quiet nights of quiet stars

Quiet chords from my guitar

Floating on the silence that surrounds us

Quiet thoughts and quiet dreams

Quiet walks by quiet streams

And a window looking on the mountains and the sea, how lovely

When the tour ended, Lees headed for New York City. He had written a novel, which he hoped to sell to a publisher, and he also had aspirations as a lyricist.

“That first year in New York was one of the most difficult of my life,” he recalled in his book Friends Along the Way: A Journey Through Jazz. “I couldn’t, as they say, get arrested. I couldn’t sell my prose, I couldn’t sell my songs. At any given moment I was ready to quit, scale back my dreams to the size of the apparent opportunities, leave New York and find some anonymous job somewhere.”

Then things started to click.

“I was the pianist on the first recording of one of his songs,” recalls the composer Roger Kellaway, a longtime Ojai resident. “The song was called ‘Fly Away My Sadness,’ and the vocalist was Mark Murphy.”

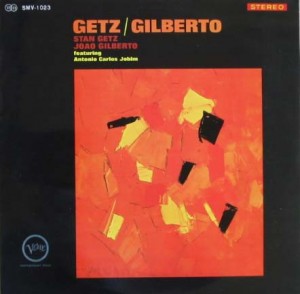

A few months later, Tony Bennett recorded “Quiet Nights (Corcovado)” for his hit 1963 album I Wanna Be Around. Then came Getz/Gilberto, an epic event in jazz history. Released in March 1964, this album by Stan Getz and Joao Gilberto transformed the bossa nova craze into an international phenomenon. The hit single was “The Girl From Ipanema,” for which Lees did not supply the lyrics. But he did write the album’s liner notes, and the LP also featured Astrud Gilberto singing Lees’s version of “Corcovado.” (The English version eventually would become better known as “Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars.”)

Lees had made a successful transition from journalist to songwriter. His lyrics for his friend Bill Evans’s tune “Waltz for Debby” became another standard. But there was a cloud on the horizon, because 1964 was also the year of Meet the Beatles. Rock ‘n’ roll was the coming thing, and sophisticated jazz-pop songs — the kind Lees wrote — would soon be on their way out.

“Oh my God, he hated the Beatles,” recalls his widow, Janet Lees, chuckling at the memory of Gene’s bitter fulminations against rock music.

The next few years constituted a kind of Indian summer for jazz singers, who continued to score occasional Top 40 hits. Lees had the privilege of watching Frank Sinatra record “Quiet Nights” for the classic 1967 album Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim. Lees also supplied the lyrics to “Yesterday I Heard the Rain” for Tony Bennett, and he translated “Venice Blue” for Charles Aznavour.

“Venice Blue” also was recorded by the rocker-turned-crooner Bobby Darin, whom Lees considered a talented singer. This association with Darin “was probably about as close to the pop industry as he ever got,” Kellaway said of Lees, his old friend and frequent collaborator.

Kellaway himself was more adaptable; he went on to work with the likes of George Harrison. But Lees could not accommodate himself to the new order.

“Had Gene been born sooner, he would surely have been as famous and successful as the top songwriters of the ’30s and ’40s,” the Wall Street Journal critic Terry Teachout wrote after Lees’s death. “But he came along after the cultural tide of jazz had started to ebb … Not surprisingly, he despised rock, which he believed had laid waste to the lost musical world of his youth.”

As he turned 40 in 1968, Lees faced diminishing prospects as a songwriter. His personal life was also unsettled after two failed marriages (one of which had produced a son). Then Lees met Janet Suttle. By 1971 she was Janet Lees, and they were living in Toronto, where Gene ran Kanata Records. (Among the albums he put out during this period was his own Bridges: Gene Lees Sings the Gene Lees Songbook.)

As he turned 40 in 1968, Lees faced diminishing prospects as a songwriter. His personal life was also unsettled after two failed marriages (one of which had produced a son). Then Lees met Janet Suttle. By 1971 she was Janet Lees, and they were living in Toronto, where Gene ran Kanata Records. (Among the albums he put out during this period was his own Bridges: Gene Lees Sings the Gene Lees Songbook.)

Things were looking up on the songwriting front, too. The legendary director Joshua Logan was developing a new Broadway musical called Jonathan Wilde. Composer Lalo Schifrin, already famous for his Mission: Impossible theme, was writing the music. Logan brought Gene in as the lyricist. “Logan told Richard Rodgers, ‘I’ve found the next Hammerstein,’ ” Janet Lees recalls.

The job required Gene to make frequent trips to Southern California, where Schifrin was based. Eventually, Gene and Janet made a permanent move from Toronto to Tarzana, where they bought a house. To their great disappointment, Jonathan Wilde was never produced, due to a legal dispute between Logan and the show’s original writers. But Gene kept busy with other projects, such as collaborating with Roger Kellaway on the songs for an animated film, The Mouse and His Child. There was still a market in Hollywood for the sort of lyrics he wrote, even though rock music and disco now completely ruled the Top 40.

But Lees’s career was about to enter an entirely new phase. And the turning point can be traced to a weekend trip he and Janet made to Ojai.

LEES already knew Ojai fairly well. “He used to come up here and work with Lalo Schifrin, who had a house behind the Presbyterian Church,” Janet said. But on one particular weekend, sometime in the late ’70s, something special happened. The clock-radio alarm in their motel room was tuned to the only station in town: KOVA-FM, owned by jazz expert Fred Hall. On Sunday morning, Gene awoke to sounds he did not readily associate with small-town living.

“I heard first Count Basie, then Jack Jones, and a man who discussed them with great knowledge,” Lees later wrote. “This brought me to full wakefulness, and when I heard the station’s call letters, I telephoned and spoke to him. That’s how I met Fred. He invited me to visit the station, which I did later that morning.”

Ojai in those days was something of a jazz hotbed. The famous trumpet player Maynard Ferguson lived here. The annual Ojai Music Festival always included a jazz component, organized by Fred Hall and Lynford Stewart. Later on in the ’80s, Wheeler Hot Springs began to host performances by the likes of Ray Brown, Mose Allison, Charlie Byrd and the Manhattan Transfer. At the heart of it all was Hall, whose radio show “Swing Thing” reached a national audience via syndication. Gene and Janet immediately hit it off with Fred and his wife, Gita. The Leeses also fell in love with Ojai, a place where quiet nights of quiet stars are almost a nightly occurrence. At some point, Gita asked the obvious question: “Why can’t you live here?”

The answer, essentially, was “No reason at all.” The Leeses left Tarzana behind and rented a house on Signal Road. Later they moved into an apartment complex in the Mira Monte neighborhood, before eventually settling in house high up on Foothill Road. Gene, Fred and Lyn Stewart teamed up to produce the “Jazz At Ojai” concerts in Libbey Bowl. And Gene turned from writing jazz lyrics to writing jazz essays.

The catalyst was the 1981 death of his friend Hugo Friedhofer, the distinguished film composer. To Gene’s immense frustration, he could not persuade the New York Times to run an obituary. The giants of his era were passing, and nobody seemed to be noticing. It was time for Lees to return to his roots as a journalist, to memorialize their achievements.

“That’s when Gene started the Jazzletter,” Janet said.

Lees put out his newsletter from 1981 until he died. It featured eloquent essays on a wide range of topics, not all of them jazz-related, but all of them beautifully written and brimming with passion. It became an institution in the jazz world, cherished by its subscribers.

“The Jazzletter was wonderful,” Kellaway said. “There were long, long dissertations on whatever he chose as a subject.”

He filled the Jazzletter with biographical essays, many of which were collected into books. He also wrote full-length biographies of Oscar Peterson, Woody Herman and Johnny Mercer. (At his death, Lees was putting the finishing touches on a life of Artie Shaw, which may yet be published.) Long or short, most of these profiles featured Lees himself in a supporting role, since he was always part of the story.

“Gene actually knew personally everybody that he wrote about,” Kellaway said. “He knew Basie and Tommy Dorsey. He knew everybody.”

At first, Lees continued to work as a lyricist while putting out the newsletter. In the early ’80s he acquired an unlikely collaborator: Pope John Paul II, who as a young priest had been given to writing poetry. Two Italian composers had set these poems to music, and Lees was hired to translate them into English lyrics. The result was a song cycle that was performed in a special concert in Germany, with vocals by Sarah Vaughan. The concert was recorded, but no major record company was interested, so Gene and Janet put the record out themselves with the title The Planet is Alive … Let it Live!

After that experience, Lees focused more on prose than poetry. His readers — and his friends — were seldom in doubt about where he stood. He liked to drink and he liked to argue, and the combination was not always pleasant for the people around him. Nevertheless, the jazz critic Doug Ramsey enjoyed jousting with Lees.

“He had strong opinions about everything,” Ramsey wrote in his Lees obituary. “We argued. Arguing was half the fun of knowing Lees. Every argument with Gene was a win for me because I had learned from him.”

Lees suffered from ill health during his final years, but he kept on writing — and not just about jazz legends from the past. One younger singer he admired was Diana Krall, who returned the compliment by recording his best-known lyric as the title song of her most recent album, Quiet Nights.

During Gene’s three decades in Ojai, the town lost some of its jazz chops. Fred and Gita Hall sold the radio station and later moved away. Wheeler Hot Springs closed, and the Ojai Festival stopped featuring traditional jazz. But Ojai remained well known in the jazz world as the home of Gene Lees and the Jazzletter. (Gene and Janet also deserve credit for bringing the violin virtuoso Yue Deng to live in Ojai, after they took her under their wing and introduced her to jazz.)

When Gene died on April 22, 2010, Janet was stunned by the outpouring of tributes from jazz writers and musicians across the globe. Eulogies were printed as far away as London, where the Times called Gene “one of the most dazzling lyricists in popular songwriting, and the Boswell to a generation of jazz musicians.”

“I just didn’t think of him as being so well-known all over the world,” Janet said.

In Ojai, not so much. Yet it was here that the man who wrote “Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars” finally found his own Corcovado, after first finding the person to share it with. Here’s how the song ends:

This is where I want to be

Here with you, so close to me

Until the final flicker of life’s ember

I who was lost and lonely

Believing life was only

A bitter tragic joke, have found with you

The meaning of existence, oh my love

This article originally appeared in the winter 2011 issue of the Ojai Quarterly. Republished here with permission. Janet Lees died in 2013. Gene Lees’s Artie Shaw biography has not been published. (Posted by Mark Lewis, December 2014)

Gene and I grew up together in Hamilton, St.Catharines,Thorold and Niagara and spent many days as young teenagers among the heavy rocks and boulders of Niagara Falls, Ontario –then later met often when he was Editor of Downbeat in Chicago. I exchanged phone calls with his wife Janet up to and the day following his death in Ojai .Gene’s parents Dorothy and Harold were wonderful individuals.During WWII Auntie Dorothy was a white hot rivet tosser and Uncle Harold a welder on Canadian Military Frigates built for the Canadian Navy in Esquimalt,B.C. Great moments for us all. Evan Griffiths