Our Town, Part 1 by Helen Baker Reynolds

When the Bakers arrived in the Ojai Valley in 1886 they came in a horse-drawn stage. At that time there was no railroad up and down the coast. About ten years later, when a coast line was under construction, a track was laid from Ventura to Ojai, and from then on, a local train with two small, creaking passenger coaches puffed into our station each evening and out again in the morning.

The village during my early childhood was still very quiet and small. Businesses extended one block along Main street, a segment of the east-west county road. Even in the business block the roadway curved casually around trees, and a hitching rack and drinking trough occupied most of the southerly side. Blumberg’s Inn, already ramshackle, stood in a grove of oaks.

On the opposite side of the street a boardwalk ran past a straggling row of establishments, general merchandise, grocery, and hardware stores, a blacksmith shop and a drug store. At the end of the block stood Schroff’s Harness Shop; at the other end Tom Clark’s Livery Stable. There was also a pool hall which we were taught not to glance into, it being not quite “nice”.

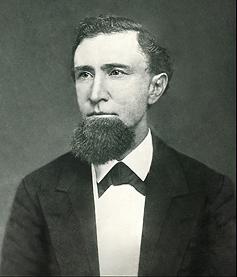

Dr. Saeger owned the drug store. In the rear was his medical office, where he doled out quinine or calomel pills, and where he also extracted teeth.

He was slow of motion and slow of speech and wore a drooping mustache. At a patient’s bedside he would sit solemn and silent; yet somehow his presence was immensely reassuring for he was a deeply kind man. My parents, who were devoted to him, used to say that Doctor Saeger never had been known to press a patient for payment, and usually he presented no bill until he was asked to do so.

Occasionally in the event of a very critical illness, request for consultation was sent to Doctor Bard, a remarkably skilled physician, who, like Doctor Saeger, practiced medicine in the best tradition of the old-time country doctor. He lived in Ventura, fifteen miles away, but, in spite of the distance and sometimes in spite of storms and floods, he would set out at once behind his spirited span of horses, in answer to a call. My family held him in reverence. He had come to attend little two-year old Sara when she was ill with pneumonia, and my parents believed probably rightly that he had saved her life.

A short distance west of the village a tiny, boxlike wooden building stood under spreading oaks. This was the jail, which Andy Van Curen, the perennial constable, had built on the grounds of his home. The jail was seldom put to use, for ours was a law-abiding town, only occasionally disturbed by some show-off galloping recklessly thru Main street, or someone being drunk on a Saturday night.

A gentle, slow-moving man of indeterminate age, Andy Van Curen had held his position for years. As the population grew and became a trifle more worldly, someone started a movement to elect a younger, more active man as constable. Andy was hurt and incensed. He let it be known that if he were replaced no one else could use his jail. The movement for replacement promptly collapsed.

Andy acted as undertaker, as well as constable. He kept a supply of coffins in a shed behind the jail. Children would peep through the tiny windows, shivering pleasantly at the sight of the coffins stacked inside. Processions to the cemetery in early days, I am told, were led by Andy transporting the departed in his spring wagon. Later, however, a horse-drawn hearse would be brought up from Ventura on the occasion of a rather pretentious funeral. The hearse was black, adorned with tassels, and the two black horses were elegant with black plumes on their heads.

Essentially our main street could have been duplicated in hundreds of small Western towns’boxlike buildings with false fronts, a few loungers in front of the pool hall, buggies and wagons raising dust or scattering mud, according to the weather.

But somehow the main street of Ojai was not altogether ugly. The ancient oaks spreading their branches over the drab little buildings, the backdrop of foothills and mountains entered competition with man and easily won the contest. In spite of human ineptitude, our village was attractive.