Sharing the history of the Ojai Valley

The Ojai: Pink Moment Promises, by Patricia Hartmann

The simplicity of Ojai farm girl Meggie Baxter’s life is shattered when she must choose between loyalty to her rough-hewn friend, Rusty, and the dashing Charles.

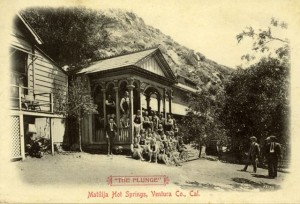

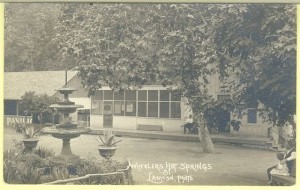

As the decades of her life unfold, she faces the elemental dangers of floods and fire as well as the colorful high-jinks radiating from Pop Soper’s Fight Camp, the steam baths at Matilija Hot Springs, a leaning post office tower, a corrupt councilman and Libbey’s plans to modernize the town.

Amid tragedy and loss, Meggie clings to the one constant in her life, the promise of God’s love. It is the ‘pink moment,’ the evening sunset casting a rosy hue like a prayer across the Topa Topa Mountains, that points her again and again to faith and courage.

Midst the idyllic beauty of the Ojai Valley and the crushing forces of change, will Meggie and her beloved Ojai stay true to their rural roots of faith and family? Will the ultimate sacrifice that spares Rusty’s life be enough? Or will the winds of destiny destroy both the people and the indomitable spirit of the Ojai?

____________________________________

The following excerpt (Chapter 11) takes place at Christmastime, 1916.

To purchase the full book, visit www.patriciahartmannbooks.com, order from Amazon.com, or purchase at the Ojai Valley Museum.

“All that Glitters” 1916

“Hey, Trooper. Easy boy…It’s OK.” Rusty spoke soothingly as he forked some hay into Trooper’s trough for his evening feed. The big chestnut gelding held back a few moments before moving forward to eat. Pa’s horse was showing telltale signs of abuse. A slight skittishness. Some scarring along the flanks. A wary look to the eye. It saddened Rusty in a way he couldn’t quite come to grips with. Everything Pa touched suffered. Trooper had been a fine, handsome horse when Pa won him off a fella in a poker game a few years back. Rusty made sure Trooper was well fed, but he couldn’t control what happened when Pa was drunk and in the saddle.

Rusty tried to reassure the horse with a gentle rub along the neck and a few soft words. “It’s okay fella…That’s a good boy.” The animal flinched slightly before blowing a stream of air out of flared nostrils and finally relaxing into Rusty’s touch. As he rubbed behind Trooper’s ears, Rusty noticed that the horse favored his right forefoot.

“Easy now, boy…Let’s have a look.” Rusty wedged his back against Trooper’s shoulder, shifting the animal’s weight off the front foot. He lifted the foreleg back and examined the hoof. The worn shoe was missing a nail. A second nail had worked loose and was protruding about a quarter inch from the bottom of the loosened shoe. Rusty grabbed a hammer and pounded the nail back in. “This is only a quick fix, Trooper. You’ll be needin’ to see Charlie Gibson at the blacksmith shop right away…if’n I can get Pa to part with the money.” If not, maybe Rusty could work it off mucking out stalls.

The days were shorter in these cooler days of December. Already the sun was starting to set. Rusty hurried to finish his chores while he still had light.

Moving to the pig shed, Rusty checked on the sows. Nine of them were nearing their farrowing time. Pa bred them too early – spring piglets had a better start in life. The sows all seemed steady on their feed. None of their teats leaked milk. Looked as if they’d hold off a few days yet. After scratching a few of the rounded backs with a stick, Rusty hefted a metal bucket he’d held back from his earlier milking of the gentle Guernsey cow. He poured a little of the rich white liquid to the pig troughs. Rusty wished he had some good corn to fill out the slops. They’d produce better with richer feed. But Pa’s only interest in corn was if it could be made into whisky.

Rusty sighed and straightened up. He headed to the wash barrel by the back door. Tonight was the big Christmas party at Thacher School. He needed to get cleaned up and dressed in his Sunday best. Rusty struggled to rouse some lather from the remnant of the cracked lye soap bar.

His thoughts turned to the night ahead. Good thing it’s within walkin’ distance. Even if’n Pa would let me ride Trooper, that wouldn’t be smart. Good way to lame a horse.

A tinge of anticipation countered the shivers from the cold water. The big Thacher Christmas hoopla. All the Nordhoff high-schoolers and the Thacher School boys were invited. Some of the older townsfolk would likely be a coming too. Meggie was sure to be there. Rusty scrubbed harder. Sure, she’s courtin’ with that Charles the III fella. All the more reason to keep an eye out fer her.

_____________________

Meggie threw a heavy flake of alfalfa into Molly’s feed trough, then held out a few chunks of carrot for the mare’s usual evening treat. Molly lifted her upper lip, revealing yellow teeth, as Meggie gently rubbed the soft pink skin of the horse’s nose. Wags bumped the back of her leg, demanding some attention too. Meggie stooped to stroke the silky black head and rub behind the dog’s ears, eliciting a rhythmic waving of his namesake tail. “OK, Wags, chores are done. And none too soon.” The sun was setting.

Meggie lingered in the barnyard, pulling her coat tighter about her, tucking her cold hands in the pockets. Yesterday’s light rain puddled the yard and the fresh smell of wet earth and damp hay filled the air. Meggie breathed in the scents and felt a quiver of excitement flood her heart. Bathed in the orange and pink hues of the sunset, Meggie had every reason to be thankful. The Topa Topas glowed pink, then purple in benediction. A few trailing rain clouds rested on the Chief’s headdress. As she turned her circle in the yard, Meggie thanked God for this day and in advance for the glorious evening ahead.

Tonight she would see Charles at the Thacher Christmas Party. This was not a box lunch or a carriage ride, but a real fairytale ball. Lights and dancing and romance. Meggie pictured herself there, clinging to the warmth of Charles’ arm. The shimmering deep blue of her formal gown matching the color of her eyes. She and Mama had spent hours stitching the dress by hand from expensive yard goods and the latest Sears Roebuck pattern.

Meggie could still see the shiny soft blue taffeta spread across Mama’s lap as she bent to make small, even stitches in the fabric. Mama’s golden hair, escaping from its tortoise shell combs, fell in soft tendrils around her face. Side by side, she and Mama had worked to fashion the iridescent fabric into a tight bodice and flowing skirt that cascaded gracefully to the floor.

The tiny seed pearls to be sewn in at the neckline and sleeves had given Meggie even more of a challenge. The pearls, carefully clipped from a castoff mourning dress Mama had found at the church rummage sale, had a very tiny center hole for threading through. It took a trip to Barrows & Son General Merchandise to find a needle thin enough to do the trick. Then Meggie had spilled the tin of pearls, watching helplessly as they bounced and skittered across the wood planks of her bedroom floor.

Chase caught her on hands and knees, searching for the tiny white beads under the bed and in the yarn of the throw rug. “So this is how Me Lady prepares for the ball…Praying are we?” He expertly dodged the pink velvet throw pillow Meggie aimed at his head. “Now…now, Meggie. You shouldn’t get testy with your carriage driver. The supply wagon just might turn back into a pumpkin.”

“And that would make you what…a rat?” From her position on the floor Meggie spied a tiny pearl near his boot. “Don’t move.”

“Why? Are you taking aim at me with your glass slipper next?” Chase grinned at her from the doorway.

Meggie rescued the pearl and stood to her full five foot one inch height to stare up into her brother’s blue eyes. She held the tiny bead in front of him. “You almost trod on a pearl of great price – you big brute.”

A smile twitched at the corners of his mouth as Chase bent to kiss the top of Meggie’s blond head. “You’re right, little lamb. I almost did.”

When Meggie tried on the finished gown and stood on a stool to see her reflection in her dresser mirror, she felt transformed into a real princess. She twirled a bit to reveal the layers of petticoat and piled her blond hair atop her head to study the effect. In the mirror she caught Pa’s reflection as he caught her admiring herself. He was smiling.

“You’re a real beauty, Meggie,” he said, leaning against the door-jam. “Reminds me of your Ma.” Pa’s eyes took on a faraway look. “When we first met, your Ma sure took my breath away. You look just like her.”

Meggie turned to face him. “Thanks, Pa. You like it?”

“Beeeautiful. Downright Baxter beautiful.” Pa stepped closer to cup her face in his hand. “It’s not just the gown, you know. The beauty that lasts comes from deep inside. You’re growing into a real beauty, Meggie. Makes a Pa right proud.”

Meggie blushed at the compliment.

______________________

Wags barked, chasing a covey of quail away from the edge of the chicken yard, bringing Meggie back to the present. The lovely gown was waiting for her. Tonight was the night. What would Charles say when he saw her in it?

Meggie tried not to think about the second part of the evening– the part that made her more nervous than excited. The part about the scholarship and Mr. Prentiss, the Cambridge/Radcliff dean, who would be waiting to meet her. What if he didn’t like her? What if her poems hadn’t impressed him? What if he thought she was too unsophisticated for Radcliff?

Quit it. Stop being so negative, Meggie scolded herself. God’s working it all out. Me and Charles. The scholarship. Getting a degree at Radcliff. Using my talents for God’s glory.” Meggie took a deep breath of the cooling air. Tonight is the start of a glorious adventure! Meggie wiped her damp hands on her skirt. She straightened her shoulders and walked toward the farmhouse and her future.

_______________________

Meggie was glad for the borrowed wool coat from Aunt Rose and the lap robe that kept her warm on the ride up Thacher Road. The three eligible Baxters-Dalton, Chase and Meggie rode on the front seat of the supply wagon as it eased into the lamplight at the front of Thacher Hall. The creaking wagon was not Cinderella’s fancy carriage, but had hauled a few pumpkins in its day. Meggie felt no need of a fairy godmother to make her dreams come true. It was a night perfect for romance.

Dalton had his eye out for his intended, Florence, who went all doe-eyed around him. Meggie knew that a whole flock of clucking females would collect in the warmth of Chase’s smile. He was a handsome and desirable bachelor, still playing the field.

Meggie’s thoughts centered on Charles and on how to best impress the respectable Mr. Prentice. In her head, she rehearsed the little greeting she’d planned for the college dean. So glad to meet you, Mr. Prentice. An honor, I’m sure.

She gave a little shake of her head. Too much reflection could spoil a girl’s special evening. Best think only of Charles, and the warm way he looked at her. Meggie intended to enjoy this rare night. A fancy ball. Christmas magic.

She smiled from pure joy as she threw off the lap robe, and stepped down from the wagon seat, taking care not to catch the hem of her gown. The rich fabric and the many petticoats beneath rustled softly as she moved. Meggie actually felt beautiful as she walked toward a night full of promise.

The entrance of Thacher Hall was warm in greeting; soft yellow light spilling out into the night from the beveled glass ovals in the massive front door. Through the large mullioned windows she could see a towering Christmas tree, beribboned pine boughs, and hundreds of flickering candles on the window ledges.

As the trio made their way up the rock steps, the door opened to the merriment of music and laughter. A pungent fragrance of pine and nutmeg-spiced eggnog tickled Meggie’s nostrils as she dared to breathe. She was really here. Meggie hung her coat on one of the hooks by the door.

“There you are…” Charles held out his hand. “Meggie…you look lovely. My farm girl transformed.”

Meggie blushed, taking his hand. “Oh, Charles. And you are…dashing.” Meggie’s gaze took in his waistcoat and tie, his neatly pressed black suit, the cut of his dark slicked-back hair. He was surely the most handsome man alive. This must be love, she thought as her throat tightened at the sight of him. Meggie took his arm to steady herself.

Her brother, Chase, pushed past the couple into the main room. “Look at this spread. Tarts, ham, pies, rolls, spiced peaches.”

“We can eat later, Meggie. Right now I want to show you off.” Charles ushered her to the dance floor where other couples already moved in time to the music. Meggie floated in Charles’ arms. This evening was a golden fairy tale, satisfying the most romantic dreams of her soul.

Meggie reined in her worried thoughts when she caught sight of Lucinda twirling past the huge candlelit Christmas tree. So what if Charles turned to stare. Who wouldn’t notice Lucinda in that bright red silk gown? It was cut daringly low at the bosom, with a long train that Lucinda held up out of the way with a braided cord looped over her dainty wrist. The young men desiring a spot on Lucinda’s dance card swarmed around her. But even the lovely Lucinda couldn’t spoil Meggie’s mood. Meggie was dancing with Charles. She closed her eyes and let the music enfold her.

She didn’t notice Rusty enter and stand in the shadow of an anteroom. She didn’t see him cross his arms in front of his best shirt as he watched her dance and spin with her beau. When the music ended and they applauded the small orchestra, she had eyes only for Charles.

Couples moved out onto the large covered porches to escape the heat of the room, taking cups of mulled cider with them. Laughter and music filled the cool night air.

The loud clatter of hoofs on the rough stone driveway rang out. Meggie looked past Charles’ shoulder as a horse and rider raced up. A rain of curses jarred the mood of the festive setting.

“Where the heck is thet no good son of mine?” Clyde Stowe spurred a lathered Trooper closer to the wall. “Rusty…get yer tail out here. Me best sow’s farrowin’ tonight. Then you sneak off to some gall durn fancy party. Get yerself home right now or there’ll be hell to pay.”

Cyclone Clyde’s words slurred. “Damn you. If’n a single piglet or me best sow dies, yer ta blame. Lazy, good fur nothing…” He cantered his lathered horse around in tighter and tighter circles at the edge of the lantern light, narrowly missing the tethered teams and wagons. Trooper limped as he struggled to obey his crazed rider. Nervous horses tied to the rail nickered and stomped their feet in agitation, shying away from the sweat-darkened chestnut gelding.

“Stupid pig-farmer.” Charles’ voice held a note of contempt.

In the shadows, Rusty moved forward. His face burned with shame. Why does Pa have to ruin everything?

He saw the shocked look on Meggie’s face–saw her turn, lock eyes with him, and look away.

Clyde jerked cruelly on the bit, pulling his horse off balance. Trooper slipped on the wet ground. “Whut the…gall durn it. Git up you lazy piece of horse flesh!” A string of profanity and the slashing sound of a whip cut through the night.

“Pa…No!” Rusty ran forward, jumping off the low wall to the drive below. He tried to grab Trooper’s reins. A slash of the whip caught him just above the eye and seared across his nose. Rusty staggered backwards, bringing a hand to his bleeding face.

“Dern bastard!” Clyde spat the words at his son and yanked on the reins, forcing his mount back on his haunches. A horseshoe dangled from Trooper’s right front hoof. It flashed for a moment in the lamplight. The horse staggered, smashing into a wagon behind him. As he tried to right himself, the gelding’s front hoof came down hard on the flopping metal shoe. The chestnut horse fell awkwardly to his knees, throwing his rider over his head. Clyde’s boot caught in a stirrup, jerking him sideways just as the gelding fell heavily on his flank, crashing into a group of wagons. The splintering sound of breaking wood, amid the screams of horses, ripped the night as the frightened teams tried to break loose and escape the turmoil.

Rusty rushed forward, putting himself in the middle of pileup. He vanished in the crush of rolling wheels, jangling double-tree hitches, and terrified horses. One arm was caught hard against a wagon bed. The crack of wood and bone rang out.

“Whoa there. Easy now.” Chase guided a wagon team away from the carnage. He, along with his brother Dalton, calmed horses and moved teams aside to free the area around the fallen Trooper.

“Pa…Pa…” A still form lay crushed under the big chestnut horse. Trooper struggled to get up on bleeding knees. Rusty ignored the pain in his right arm as he eased the horse to his feet and jerked the loose shoe off. Trooper stood-favoring one leg. The lathered horse panted heavily…trembling. In the flickering lantern light, half hidden in the shadows, dark blood poured from Trooper’s torn knees and from whip slashes on his heaving sides.

Holding the reins in his left hand, Rusty knelt beside the fallen form of his Pa. The tears that ran down Rusty’s cheeks mingled with the blood oozing from the whip cut across his eye and his nose. His Pa’s staring eyes saw nothing.

Meggie stood frozen in horror. Then she took a step forward. Charles grabbed her arm, pulling her back. “No, Meggie.”

“I have to go. Rusty needs me.” Meggie pulled free of Charles and raced down the steps to Rusty. She knelt beside him in the dirt, softly touching his shoulder.

The eyes that turned toward hers were full of misery.

“I think my arm’s broke.” Rusty’s voice was somewhere between a plea and a sob.

“It’s OK. We’ll help you.” Meggie looked up at Chase who gently tugged on Rusty’s good arm to help him to his feet.

Rusty gritted his teeth against the pain. In the wavering lamplight, Meggie saw that his right arm jutted out at an unnatural angle.

“We’ll need a sling,” said Chase, looking around for a bit of cloth.

“Here.” Meggie lifted her skirt and tore off a piece of her petticoat flounce. Chase quickly fashioned a crude sling and eased it under Rusty’s forearm. He tied the ends behind the boy’s neck. Rusty swayed a bit. His wounded eye was swelling closed.

“Lean on me.” Meggie pulled his battered head towards her shoulder. He slumped against her.

“We got our team and wagon untangled from the lot” said Chase. “Dalton and I’ll take you to the Doctor.”

“Trooper…I can’t leave him.” Rusty looked over at the injured animal. “And Pa…what will …?” Rusty couldn’t finish the sentence.

Sherman Thacher stepped out of the crowd, holding a blanket in his arms. “Don’t worry, Rusty. I’ll handle it…and later the buryin’ too.” He moved to cover the body of Clyde Stowe. “You go along now to the Doc’s. We’ll tend to Trooper at our stables. Try to save his knees. You’ve my word on it”

Rusty nodded and handed the reins into Sherman Thacher’s hand. He took one last look at the still form of his Pa. A patch of red hair matted with blood protruded from the top of the blanket. Worn, scarred work boots covered in mud jutted up past the bottom edge. The boots–like those of Billy Soule–lay stone still.

He’ll never hurt Ma or me again, thought Rusty. Never again. So what was the sharp ache in his chest? Rusty tried not to think about it.

He winced in pain as Chase and Dalton helped him up to the wagon seat, setting Molly off at a trot into the night. Rusty wiped blood from his cheek with his left hand and let his good eye fall closed. There was nothing else he wanted to see tonight.

__________________________

Meggie watched as the body of Cyclone Clyde was hefted into another wagon for his last trip into town. An empty whiskey bottle fell from his jacket pocket, shattering into sparkling shards on the hard, cold ground.

Meggie wondered how a night that began with such glittering promise could have turned so tragic.

Slowly, the crowd drifted back inside. The music began to play once more.

“Meggie?” Charles came down the walk to usher her inside. Just inside the hall, where the light was better, he stepped away from her. He stood a few feet away, a strange look on his face. “Whatever were you thinking?”

In the crowd gathering behind Charles, Meggie saw the red silk gown. Lucinda’s face held a satisfied smirk as she moved aside to let an older gentleman pass. The man, dressed in a three-piece woolen suit with silk shirt and black tie, came to stand beside Charles. Meggie noticed that his shoes were spit shined, the cuffs of his tailored pants neatly pressed.

Charles gave a nervous cough. With a look Meggie could not fathom, he stared right through her as he made the formal introduction.

“Mr. Prentice…may I present Miss Megan Elizabeth Baxter.”

Meggie started to extend her hand, but stopped midway. Her hand was smeared with blood. In the beveled glass of the entry door she caught a glimpse of her reflection. Her cheeks were streaked with dirt and tears. Her hair, having come loose from its pins and combs, hung in a few bedraggled clumps around her face. Smudges of mud stained her lovely blue taffeta gown, which had a few jagged holes at the knees. The right shoulder of her dress was marred with darkening blood. Shreds of white petticoat drooped out from underneath.

Meggie struggled to think…to breathe. What words had she practiced?

“An honor, Mr. Prentice,” she said in a barely audible voice, backing away. “If you’ll kindly excuse me…I’m afraid I’m not myself tonight.”

With flushing cheeks, Meggie grabbed her coat off the hook and fled out the door, stopping by the nearest lamppost. Charles followed at a safe distance. “Meggie…that was quite a show. Your big chance to get into Radcliff and you decide to play nursemaid to a pig farmer.”

Charles paced back and forth glaring at Meggie as if seeing her for the first time. “You have to decide what you want, Meggie. An education at a college back East or a being stuck in a backwoods place like Ojai–all your talents wasted.”

“I do want to go to college…It’s my dream. All those books, a real library…a chance to learn…” Meggie shivered in the cold and pulled her coat closer about her. “But…”

“But you just couldn’t help yourself, could you?” Charles’ brow furrowed as he squinted at her. “They take ladies at Radcliff, Meggie. They have a reputation to maintain.”

“But I…” Meggie struggled to explain herself. “I had to help.” She was becoming angry that she needed to explain.

“Oh I see…” Charles took a sarcastic tone. “You can take the girl out of the farm – but you can’t take the farm out of the girl.” Charles gestured at the muddy rutted driveway, the ragtag collection of wagons. “Look around you, Meggie. Is this what you want?”

Meggie looked up at the bright sparkle of stars strewn across the sky. The dark mass of the Topa Topas rose in front of her, surrounded by the black lacy edges of valley oaks silhouetted in the faint moonlight. Meggie’s breath frosted in the cold air as she spoke. “Ojai is my home.”

“Well, you’re welcome to it, then.” Charles smoothed back his dark hair with a well-manicured hand. “I’m so glad we had this little talk.” He gave an exaggerated bow. “Goodbye Meggie.”

Charles turned back toward the laughter and gaiety of the Christmas party, leaving Meggie alone. The woman in a low-cut red gown took his arm at the door.

Meggie drew in a deep breath. She took one last look at the glittering hall. Then she turned back toward the steep road home. My only regret, she thought as she strode into the darkness, is that I’m not wearing my sensible walking boots.

Order The Ojai: Pink Moment Promises from Amazon.com, www.patriciahartmannbooks.com or purchase at the Ojai Valley Museum.

Tribute to Larry Hagman, by Michael Shapiro

Larry and his wonderfully cheerful wife Maj were long-time friends and protectors of Ojai. They opened-up their grand home “Heaven” on the top of Sulfur Mountain, on countless occasions in support of issues and candidates that might benefit the Ojai Valley.

One of those events quietly yet strategically may have played a vital role in the defeat of Waste Management’s attempt to develop one of the largest landfills west of the Mississippi at the southern entrance to the Ojai Valley’s air-shed at Weldon Canyon.

With just a couple of weeks before the Ventura County Board of Supervisors would vote whether or not to approve the ruinous, polluting boondoggle Larry and Maj hatched a plan: They would host a simple, casual lunch “outside on their home’s patio” for the five County Supervisors who would soon cast their votes whether to approve the Weldon Dump project.

Besides the delicious, classy food and wine, Larry arranged for five tripod-mounted, powerful-military-grade binoculars to be assembled and locked into place, all facing south. At the appointed time he invited each of the County Supervisors to stroll over to take a look out from these binoculars.

As they gazed through the powerful magnification Larry explained that besides the spectacular views of

the southern slope of Sulphur Mountain, the Ventura Beaches, the blue Pacific and the Channel Islands floating in the distance, that just a few miles away (as the crow flies) was Weldon Canyon. In fact, that’s where the binoculars had been focussed on.

Larry shared that given that he and Maj owned perhaps one of the largest parcels of property in Ventura County “with a considerable annual property tax assessment” he felt as if the proposed Weldon Dump would basically destroy their home’s value and adversely affect the healthy and welfare of anyone breathing the air around there, as well as most of the Ojai Valley given that daily prevailing breezes would carry tons of particulate matter annually into the Ojai Valley’s air-shed.

It must have made an impression: On the eve of the Supervisor’s vote a few weeks later Waste Management withdrew their application when they realized that they simply did not have the votes for approval. However, that didn’t yet stop them: Waste Management then decided to make an end-run around the administrative process and try getting the horrid dump proposal approved in a County-wide ballot initiative with millions of dollars to pay political consultants and lawyers to wage the campaign.

Larry and Maj once again stepped-up to the plate and hosted an intimate yet spectacular benefit concert with Kenny Loggins, David Crosby, Chris Hillman (of the Byrds) and Bernie Leadon (of the Eagles) performing in their living room. The proceeds from the concert helped kick-off the Dump Weldon Coalition’s own campaign to defeat Waste Management at the polls a year later.

Years later when I’d just returned from my first of many end-of-summer journey’s to Burning Man I bumped into Larry at Ojai’s downtown arcade and shared some of my experiences of my first venture at Burning Man. I recall pointing out to him that he had the most perfect Burning Man home in his spectacularly restored minted Airstream RV which I’d seen years earlier.

I must have planted the seed, for a year later, as I was riding my bike around Blackrock City (Burning Man is held on the great Blackrock Desert Wilderness and is highly organized into a bone fide “city”) I accidentally rode past a most wonderful sight: Larry Hagman, adorned in a kaftan and turban and holding court outside his vintage airstream designed like part of the set from I Dreamed of Jeannie, right there at Burning Man!

Larry is best remembered by me as an older man who had never allowed his ‘inner child’ to depart from his being! Those of who had the change to interact with Larry and Maj will surely miss them and those exciting days frolicking with them in “Heaven” right here on earth!

Civic Improvement Ojai, California

How an Old, Uninteresting Town Was Made Beautiful

By FREDERICK JENNINGS

Architect & Engineer August, 1919

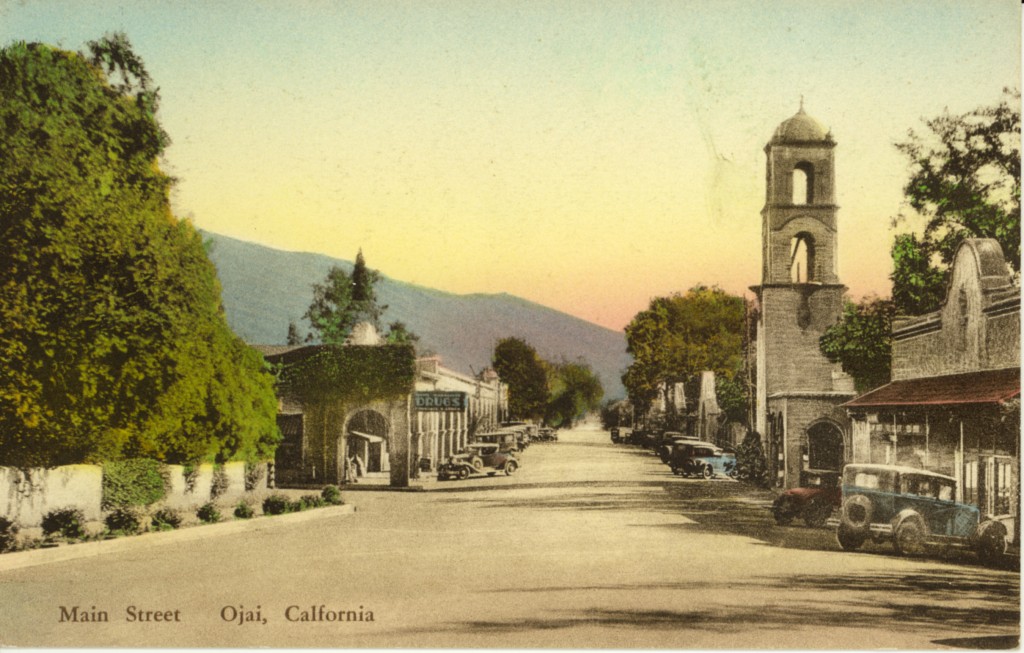

LESS than three years ago what is now the quaint mission village of Ojai, California, was a ramshackle old town called Nordhoff in a mountain pocket forty miles south of Santa Barbara. It was an eyesore to the owners of the beautiful estates in the vicinity, and one of the owners, Mr. Edward D. Libbey, undertook to remedy the evil. His hopes for the town’s rehabilitation were grounded in a belief in the psychological effect of good clothes, translated in terms of architecture.

It happened that all of the stores stood on one side of the street, and Mr. Libbey’s first step was to purchase ten acres of ground on the other side, which included a number of dilapidated old shacks. This accomplished, the task of beautification was begun. The old buildings were torn down and in their place appeared a garden and tennis courts. A grandstand was erected, and along the edge of the park which fronted the street was built a Spanish pergola. But before this work was completed it began to be borne in upon the store keepers that their buildings looked disreputable in contrast, and at the psychological moment Mr. Libbey proposed that he would give them the park and tennis courts, and a new post office building, if they would join together and freshen up the appearance of their store buildings. The offer was accepted and Mr. Libbey thereupon engaged the services of Messrs. Mead and Requa, architects of San Diego, to plan a new business thoroughfare for the town. It was discovered that by a slight expenditure on the part of each store owner, a uniform front could he built on all the stores. So the workmen were called in and the task was begun. The store buildings themselves were not disturbed, but an arcaded plaster front was built on all of them. The transformation was complete. Each store owner put up a few hundred dollars, and in return became the possessor of a building enhanced in value and beauty beyond all proportion to the amount of money spent.

But the idea which created the transformation, the idea of giving a man good clothes and seeing him live up to them, did not stop there. Ojai’s fame as a village has spread. Committees of citizens have visited it from various places in the state, and already half a dozen small villages are planning to do what Ojai has done.

Writing of civic improvements in general and the Ojai community in particular, Mr. Richard S. Requa says:

“A great deal of attention has been given during recent years to the matter of Civic Improvements. Volumes have been written on the subject, committees and conventions have frequently met for its discussion, and almost every progressive American city has either its city planning commission or has under consideration plans prepared by authorities on city planning and beautification.

“In almost every instance, however, the larger cities only have agitated or attempted plans or work along these lines.

“The village or small town has received slight encouragement and has shown little disposition to initiate the movement. This is not because the resident of small communities does not appreciate or enjoy well-planned and beautiful surroundings, but because the expense entailed is usually considered far beyond the amount they could raise for such purposes. The small town is usually burdened to the breaking point providing funds for the erection and maintenance of schools, fire stations and other administrative and public buildings. In a large majority of cases, however, a careful study of the situation would demonstrate that a great deal could he done in the way of unifying and transforming the ugly and jarring elements of a village street into a harmonious and pleasing group at a cost no greater than would be necessary to remodel and modernize the individual store fronts. Public service corporations, banks, realtv firms and other firms and individuals interested in the growth and development of the community will be found most willing to contribute to the undertaking.

“So far as I know, the credit for initiating the movement for small town improvements should be given the village of Ojai (formerly Nordhoff) in the Ojai Valley, Ventura County, California. This community is so small it is not incorporated, has no local government and no means of raising money except by voluntary contributions. Fortunately it is most favorably situated in a beautiful valley at the terminus of a concrete highway, fifteen miles from the sea and the city of Ventura. Lofty and picturesque mountains hem it in on all sides and nature has embellished it with running brooks, giant oaks and semi-tropical flora. The only discordant note in the valley, the one blot on the landscape, was the business section of the village, a collection of nondescript and ramshackle buildings with ugly metal awnings, disjointed sidewalks and crude, staring signs. A partially wrecked livery stable and a dilapidated blacksmith shop occupied the two most prominent corners of the town.

“Mr. E. D. Libbey of Toledo, Ohio, a winter resident of the valley, possessed the foresight and imagination to realize the possibilities of unifying and beautifying the conglomeration at a surprisingly small expense compared with the result obtained, fie appealed to the public-spirited residents and property owners to aid in the undertaking and by way of encouragement proposed to buy and deed to the community a beautiful tract of ten acres (an old hotel site) in the center of the business section, as a civic and recreation center and also to erect a post office on the site. The appeal met with instant cooperation and success. Each shop owner agreed to pay a certain pro-rata share of the expense, and the balance of the amount required for the improvements was contributed by property owners and business interests in the valley.

“The Spanish Colonial, or the so-called Mission style was decided upon as the logical and best adapted treatment for the regeneration. Within three months after the idea was proposed, the money was raised, the plans were completed and the actual work commenced. The construction is fireproof and permanent; hollow tile, reinforced concrete and stucco being the materials used.

“The local benefits, however, are insignificant compared with the example set and the incentive given other towns to improve and beautify their surroundings.”

In designing and planning the village hotel or tavern for Ojai, the special problems to be given careful and special consideration and study were: a building thoroughly modern and up to date and meeting the requirements of the discriminating traveler; a plan and arrangement that will furnish suitable accommodations “for the commercial man, the casual visitor and the tourist, and also provide a pleasant, restful home for the guest who desires to extend his sojourn over weeks or months; a structure that will be sunny, warm and comfortable during the cool days of winter and also be cool, airy and restful during the heat of summer; a’ design conforming and harmonizing with the present civic improvements, of which it forms a part ; and providing by means of treillage, pergolas and broad, plain wall surfaces the greatest facility for the growth and development of the vines, plants and shrubs so essential for maintaining the verdant charm and country atmosphere of the village.

Before the plans were started, the most successful Southern California hotels were visited and hotel men of experience and authority were consulted, and the practical knowledge thus gained was used in developing a plan which meets in the highest degree possible, in a building of its modest size and cost, the needs and desires of the traveling public.

The very essential matters of light, heat, ventilation and view were carefully considered and adequately worked out. A large, comfortable, homelike lobby and out-door sitting room have been provided to tempt the guest to prolong his stay. The dining room has been made especially airy and attractive. The two sides of the room facing east and south are practically all glass, looking out upon an interesting California garden and commanding a most fortunate view of the post office tower, the park, the pergolas and arcades of the main street and the wooded hills beyond. The entire east side opens, by means of French windows, onto a generous pergola-covered terrace, shaded and sheltered by a large spreading live oak.

The building and the enclosing garden walls have been designed in the spirit of the early Spanish Colonial and California Mission architecture to fit into and form a part of the already completed civic improvement scheme. The main features are the plain, modeled, plastered wall surfaces, dull varicolored roofing tiles; quaint, overhanging balconies, interesting window lattices and grilles and rustic log-covered pergolas, all so reminiscent of the early Spanish inhabitants and fitting so harmoniously into its semi-tropical environment. A simple, vet imposing Mission arch breaks and relieves the straight lines of the enclosing garden walls and serves as the main entrance to the grounds and the tavern.

The Transformation of Ojai, by Richard Requa

San Diego Union 1925

One morning in early spring, some 10 years ago, two men were sitting on the edge of a raised rough plank sidewalk in front of a dilapidated shack.

A remnant of a sign over the battered, creaking door informed the curious visitor in letters hardly legible, that hte shanty housoed the Nordhoff postoffice. It was but one of a group of decaying structures that formed the business center of a small community all but hidden among the trees of a magnificent grove of liveoaks in one of the most picturesque of California’s foothill valleys.

Few people outside of Ventura county had ever heard of this beautiful little valley whose quaint name, Ojai, meaning nest, was given it by its original inhabitants, the Indians.

PROJECT PRACTICAL

The two men were E. D. Libbey, glass manufacturer of Toledo, and his life-long friend, H.t. Sinclair. Both had found the valley quite by accident and had become so impressed and charmed with its beauty, they built winter homes there.

Seated on the plank walk they were silently contemplating the row of ramshackle shops across the road. On one corner was a livery stable in advanced stages of decay, and opposite stood the remains of the village blacksmith shop, both reminiscent of the days of horse-drawn vehicles. Suddently Mr. Libbey turned to his companion and remarked that he would like to do something for the community, something original and worthwhile.

“Why not make it over into a quaint Spanish town, in the spirit of the early California and Mexican settlements,” replied his friend. “A splendid idea,” rejoined Mr. Libbey.

In response to a telegram, I appeared on the scene the next day, and the feasibility of the scheme was discussed. After several days of study and sketching, the project was found to be entirely practicable and in addition, the transformation could be made at a surprisingly small cost considering results attainable. All but a few of the store buildings occupied one side of the main street and extended some 500 feet in almost a continuous line. The opposite side was given over largely to a spacious grove of oaks and sycamores in which stood the ruins of the old village hotel.

CRITICS OVERRULED

Mr. Libbey agreed to purchase this site and dedicate it to the community as a public park in addition to erecting a new postoffice and otherwise improving that side of the street, providlng the property owners in the valley would raise funds sufficient to make over the store buildings.

His generous offer was eagerly accepted and in less than a month the obscure village was a scene of boom-like activity.

On the site of the stable rapidly rose the walls of a modern garage, while the blacksmith shop gave way to the new postoffice with its picturesque Spanish tower. The stores were relieved of their ornate cornices, iron awnings and other incongruous embellishments, and brought into harmony and unity by means of the familiar Spanish arcades.

Six months from the date of its inception the wonder had been wrought and the transformation was complete. Brick, tile, concrete and wood, fashioned into arches, dressed and aged with stained warm-toned stucco had performed the modern miracle.

Critics and skeptics who had dubbed the venture an impractical, idealistic dream were soon to realize the error of their predictions. Hardly had the work been finished when the county of Ventura voted bonds to build at great expense a concrete highway into this mountain valley. The fame of this novel and worthy achievement spread with gratifying rapidity.

Newspapers and magazines pictured and extolled its charms and beauty. Even writers of popular fiction referred to it in their romantic tales.

FAVORABLE ADVERTISING

As an inevitable result of such favorable advertising many visitors became property owners in the valley, materially stimulating and raising the values of real estate. Men of wealth have purchased estates and established winter residences there. The steady gain in population has been marked with increasing building activities. The majority of the new homes are fine examples of California architecture, designed to harmonize with the civic improvements. Lately a country club and golf course, one of the finest in America, has been added to the many recent attractions.

So successful has been this experiment of enhancing the natural advantages and beauty of a community with consistent and harmonious architectural development that the neighboring city of Santa Barbara has created a civic center designed in similar spirit of the early American ranchos.

This plucky, far-sighted and public-spirited little city is carry on a campaign of popular architectural education that is producing splendid results.

The reconstruction of their business street, made necessary by the earthquakes, is being done as far as possible in the harmonious architectural style of the civic center. Santa Barbara bids fair to emerge from her recent disaster one of the most interesting, picturesque and architecturally beautiful of American cities.

Almost at the threshold of the city of San Diego a most unique, ambitious, and successful and development project has been quietly under way for some two years. Ushered in without brass bands, tent meetings or other spectacular stunts and accomplishments, the work has gone steadily forward along a definite and practical though strikingly original, plan.

DREAMS REALIZED

Greatly impressed with the success of the Ojai venture, the Santa Fe Railway company decided to attempt an even more novel and educational experiment in developing their extensive properties, an original Spanish grant, located some seven miles northeast of Del Mar.

Starting with a clean canvas, they determined to create there a business and civic center in the material form as well as the spirit of the early Spanish American ranchos. The surrounding property, some 900 acres, would be divided into small ranch tracts, served by an excellent system of highways leading from the civic center. Every house and other structural improvement must be designed to conform and harmonize with the general scheme.

The railroad’s dream is proving a reality. People seeking congenial homesites and environment, and the health-giving advantages of outdoor life are being attracted there from all over the nation. Building operations have been continuous since the start of the work and many fine homes in the beautiful southern California style are crowning the knolls and enlivening the landscape.

Perhaps you are wondering what the recital of these architectural exploits has to do with the subject of this article. It has indeed a most vital bearing on the particular point I want to make.

These illustrations are most pertinent in evidencing the fact that appropriate and harmonious architectural developments in any southern California community pays, and pays handsomely, to an extent that no other enterprise or amount of advertising can do.

1922 Biography of Richard S. Requa from Clarence A. McGrew, City of San Diego and San Diego County, Volume 11 (Chicago and New York: The American Historical Society, 1922, pages 32-33.)

RICHARD S. REQUA is senior member of Requa & Jackson, architects, which recently succeeded the firm of Mead & Requa. The public generally not only in the West,. but in the East, has been made acquainted with these firm names and Mr. Requa’s name in particular by some distinctive achievements that have been widely described and illustrated and have been hailed by competent critics as a distinctive California style of architecture, involving a felicitous handling of lines and details inspired by and suggestive of early Spanish work, hut lacking the crudities of the older so-called Mission style.

Mr. Requa has been a student of the environment in which his work has been done for over twenty years. A son of Edward H. and Sarah J. (Powers) Requa, he was born at Rock Island, Illinois, March 27, 1881. His father was a merchant at Rock Island, but four years later moved to Norfolk, Nebraska, and in 1900 the parents came out to San Diego, where Edward H. Requa died at the age of sixty-four. The mother is still living.

Richard S. Requa is the oldest of three sons and three daughters, all living, and was reared and educated in Nebraska. He attended Norfolk College and early took up the study of electrical engineering. He was nineteen years of age when he came to San Diego in 1900, and he followed the general lines of his earlier professional training here until 1907, when he became associated with Irving J. Gill, then a well known San Diego architect. In 1912 he opened his own office and two years later became associated with Frank Mead as Mead & Requa. The partnership was continued until May, 1920, although during this time Mr. Mead devoted considerable attention to Government work, in which he was interested. Since then the partnership has been known as Requa & Jackson. Mr. Herbert L. Jackson was a silent member of the firm for five years before his name was added to the partnership.

The best commentary that a layman can make on Mr. Requa’s work is to point out some of the notable commissions handled by his firm.

In 1913 Mr. Requa was given practically carte blanche in re-creating and re-building the town of Ojai in Ventura County. It was the first project of the kind ever undertaken in this country. Since then Mr. Requa has been almost continuously employed in similar projects, a work that has taken him all over Southern California. In the fall of 1917 he was appointed Government Architect associated with Albert Kahn, of Detroit, for the construction of the buildings at Rockwell Field, at North Island, and these duties of a patriotic nature employed much of his time until the end of the war.

The Nurses’ Home at the County Hospital, designed and constructed by Mead & Requa, is regarded as one of the most perfect examples of that type of construction in the West. Mr. Requa was architect for the Fallbrook High School and the La Mesa Grammar School, built the Krotona Institute of Theosophy at Hollywood, and a number of residences there. One of these residences was selected by the House Beautiful Magazine as one of the three best homes in Southern California; selected by the Committee of the American Institute of Architects to go on the honor roll as one of the most perfect examples of architecture in the Los Angeles district. Some of the special characteristics of his work as evidenced at San Diego are the Paloma Apartments, the residence of A. H. Sweet, the Barie residence at Coronado. Mr. Requa is now building the San Diego Country Club at Chula Vista.

Mr. Requa is a prominent member of the American Institute of Architects, Southern California Chapter, is a member of the San Diego Arts Guild, and the Archeological Institute of America. During 1914, while touring through Cuba, Panama and the North Coast of South America he prepared a set of slides and has since used them in a number lectures to illustrate the architecture of those countries. Mr. Requa is a member of the San Diego Chamber of Commerce, and the Advertising Club of San Diego.

The Meaning of Ojai Day, by Mark Lewis

Reprinted from The Ojai Quarterly

Downtown Ojai in 1920s. Courtesy Ojai Valley Museum

Ojai Day celebrates the 1917 transformation of Ojai from a dusty, ramshackle collection of old West shops into unified design of public architecture and parks, with converging perspectives of arches and towers. What inspired Edward Libbey to transform Ojai into an architectural jewel? Mark Lewis interviewed Craig Walker, who revived the Ojai Day celebration in 1991, for this in-depth look at the origins of Ojai Day. Craig traces the impetus to the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, an epochal event that launched the City Beautiful Movement, made Libbey a vast fortune and introduced him to Mission Revival architecture.

The original plan was to call it Libbey Day, to honor the man who had transformed the dusty, dowdy, backwater burg of Nordhoff into the model Mission Revival village of Ojai. But Edward Drummond Libbey was having none of it. He was proud of his role as Ojai’s guardian angel, but he preferred to celebrate the town itself on the occasion of its rechristening, rather than focus on his role in the process. As usual, Libbey got his way. And so, on April 7, 1917, some 2,000 people crammed themselves into the town’s brand-new Civic Park to celebrate Ojai Day.

“We are celebrating here today the fulfillment of a conception,” Libbey told the crowd. On every side stood examples of his handiwork: The Arcade, the Pergola and the Post Office Tower, all immaculately sheathed in sparkling white stucco or plaster.

“There has been too little attention paid to things aesthetic in our communities and in our homes,” Libbey said. “The time has come when we should encourage in ourselves thoughts of things beautiful, and the higher ideals which art encourages and promotes must awaken in the people the fostering of the love of that which is beautiful and inspiring. We must today decry with contempt and aversion all that is cheap, vulgar and degrading.”

That night the new buildings were illuminated with white light, rendering them incandescent. The effect must have reminded some onlookers of similar illuminations they had witnessed at the Panama-California Exposition, a world’s fair of sorts that had just closed on January 1, after a successful two-year run in San Diego’s Balboa Park.

Looking back at these events across a distance of 95 years, it seems clear that Libbey’s Ojai project was heavily influenced by the San Diego fair. The Panama-California Exposition had popularized the new Spanish Colonial Revival style, a baroque offshoot of the Mission style and Ojai’s Post Office Tower would have looked right at home in Balboa Park. But one local history maven, Craig Walker, traces Libbey’s original inspiration further back, to an earlier world’s fair: Chicago’s legendary World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, better known as the White City.

The Chicago fair had an enormous impact, and still lingers in the national memory. It is the subject of Erik Larson’s hugely popular nonfiction book The Devil in the White City, first published in 2004 and still going strong on the paperback bestseller lists almost a decade later. The book focuses on a serial killer, Dr. H.H. Holmes, the eponymous “Devil” of Larson’s title, who preyed upon fairgoers. But for most people who visited the White City, it looked more like heaven than hell.

It was there, on the shore of Lake Michigan, that Edward Libbey witnessed a testing of the hypothesis he would propagate in Ojai two decades later: that beautiful buildings inspire people to become better citizens. To judge by Chicago’s less-than-sterling reputation over the years as a bastion of civic virtue, the original experiment was rather a bust. Ojai would turn out to be a different story.

MAKE NO LITTLE PLANS

The World’s Columbian Exposition originally was scheduled to open in 1892, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus discovering the New World. But its organizers got carried away. Led by the architect Daniel Burnham, they turned the fair into an epic celebration of modern America and its apparently limitless potential. “Make no little plans,” Burnham famously said; “They have no magic to stir men’s blood, and probably themselves will not be realized.”

Big plans take time to develop. As a result, the fair did not open until May 1893. But it was worth the wait. Burnham & Co. had built an entire model city in Jackson Park. This was in effect a Hollywood set, made up of temporary buildings molded out of a kind of stucco and painted white to look like marble. Nevertheless, the effect was stunning especially at night, when they were bathed in electric light. Collectively they comprised the White City, and people looked upon them in wonder.

Some 27 million people visited the fair that year, the equivalent of a third of the country’s population. Among them was the future author L. Frank Baum, for whom the White City would serve as the model for the Emerald City in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Another onlooker was Elias Disney, a carpenter who had helped to build the White City; his son Walt would one day build his own White City in Anaheim and call it Disneyland. Even the notoriously cynical historian Henry Adams was impressed with what Burnham had wrought.

“Chicago in 1893 asked for the first time the question whether the American people knew where they were driving,” Adams later wrote. The answer was still unclear, but at least the question was framed intelligently. The White City, Adams wrote, “was the first expression of American thought as a unity; one must start there.”

All sorts of people beat a path to Chicago in 1893, including the theosophist Annie Besant, who was on her way from Britain to India. She stopped off in Chicago long enough to attend the fair’s Parliament of Religions, during which Swami Vivekananda introduced America (and the West in general) to Vedanta and yoga. Such epochal goings-on were routine at the Chicago World’s Fair, which also introduced America to the Ferris Wheel, Cracker Jack candy and Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer. But its most far-reaching legacy was the City Beautiful Movement, which the White City embodied.

“The industrial cities of the 1870s and ’80s had little planning “they evolved as crowded, ugly, haphazard affairs,” Craig Walker said. Burnham built the White City to show that there was a better way. “The belief was that cities built as a unified, planned development, with beautiful public buildings and parks, would inspire civic pride and moral virtues that would bring social reform,” Walker said. “The exposition was the blueprint for modern America; it had a major influence on art, architecture, city planning, business and industry.”

Ah yes, business and industry. The exposition was not entirely about art and moral uplift. Commerce also was highlighted, and many manufacturers built exhibits to showcase their wares. Among them was a certain glass manufacturer from Toledo, who saw the fair as his chance to hit the big time.

Edward Drummond Libbey was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts in 1854. He followed his father into the glass business and by 1892 was the head of Libbey Glass. The firm had moved in 1888 from New England to Ohio, where it struggled for a few years before finding its footing. Now Libbey saw the World’s Columbian Exposition as opportunity to establish his firm as the premier national brand for high-quality cut glass tableware. But his board of directors balked at investing big bucks to build a first-class exhibit. So Libbey borrowed the money himself and built it anyway. It was a full-scale glass factory situated on the Midway Plaisance, west of the fairgrounds proper. Libbey’s gamble paid off: The Libbey Glass pavilion was a huge success with fairgoers.

Libbey spent a lot of the time at the fair, living above the store, so to speak, in an apartment built into the pavilion’s second floor. The building was located half a mile east of the Ferris Wheel and just short walk west from Stony Island Avenue. On the other side of the avenue lay the shimmering White City.

Most of the fair’s buildings showcased the neo-classical Beaux Arts style, which America’s leading architects had studied in Paris. Among the more notable exceptions was the California Building, which stood less than a quarter of a mile away from the Libbey Glass exhibit. Paris had never seen its like. Nor had Chicago, for that matter. The California Building introduced America, and Edward Libbey, to a new architectural style called Mission Revival.

ENTER RAMONA

California had not always celebrated its Mission Era heritage. After the gold rush petered out, the state’s boosters needed to give people from back East a different reason to migrate west, and California’s Spanish and Mexican heritage did not seem like a selling point for white Protestant Americans. On the contrary, the state’s boosters feared that all those Spanish-style churches and forts made California seem too foreign and too Catholic. “From the 1840s to the early 1880s, the American immigrants did everything they could to eradicate the state’s Old World Spanish architecture,” Craig Walker said. “The missions and presidios were abandoned and destroyed.”

Casting about for a viable marketing angle, California’s railroad barons brought in the travel writer Charles Nordhoff to publicize the state’s natural beauty and healthy climate. Nordhoff hit the mark with his book California for Health, Pleasure and Residence (1872), an enormous success that induced thousands of Americans to move west. Some of them ended up in the sparsely Ojai Valley, where a real estate promoter named Royce Surdam was promoting a new town site. The settlers decided to name this town Nordhoff, to honor the man whose book had lured so many of them to California.

Nordhoff’s founders took no cues from the few remaining adobe structures they encountered in the vicinity. Their new town was built out of wood, and looked like it had been plucked from Kansas or Iowa and replanted in the Ojai Valley. But not every visitor from the East was averse to adobe. When the author Helen Hunt Jackson passed through Ventura County in 1882, she ignored Nordhoff but made a point of lingering in Rancho Camulo, a Spanish-style ranch near the present-day town of Piru. Rancho Camulo served Jackson as a model setting for Ramona (1884), her melodramatic novel about a young Indian woman who lives on a California ranch during the early years of statehood.

Ramona changed everything. A runaway bestseller, it sparked a national fascination with California’s Mission Era. The state’s boosters reversed course and embraced the old missions as iconic symbols of a romantic (and mostly spurious) past. “They just rode this Ramona thing,” Walker said. In the end, Jackson’s book lured even more people to California than Charles Nordhoff’s had.

Meanwhile, California architects concocted the Mission Revival style to create new buildings that harked back to the period in which Ramona was set. Naturally, when it came time to design a California exhibit building for the World’s Columbian Exposition, state officials chose a Mission Revival motif. The California Building was hardly the first example of this new style, but it was the first one to win nationwide acclaim. It made a big splash at the fair.

“It really was the building that got America’s attention,” Walker said.

Did it get Edward Libbey’s attention? He could hardly have missed it, given its close proximity to the Libbey Glass pavilion. Was he impressed? There is no way of knowing. All one can say with confidence is that Ojai’s future benefactor first encountered the Mission Revival style in Chicago in 1893.

The World’s Columbian Exposition also put Libbey on the path to extraordinary wealth, due to the success of his glass-making exhibit. “His whole glass empire just took off,” Walker said. “It propelled him to the top of America’s glass manufacturers, and he became one of the wealthiest businessmen in the country.”

And, crucially, the fair exposed Libbey to the full effect of the City Beautiful Movement. Before long he began applying its precepts to Toledo, where in 1901 he co-founded the Toledo Museum of Art. But Toledo turned out to be too big a city for one man to beautify. Libbey continued to support the museum, but he spent more and more of his time in Southern California. In 1908 he discovered Nordhoff, and built himself a winter home high up on Foothill Road. He loved the valley’s climate and mountain scenery, but was less impressed by its tacky architecture. Eventually, it occurred to him that Nordhoff, too, could benefit from the Libbey touch.

THE VILLAGE BEAUTIFUL MOVEMENT

Nordhoff’s ramshackle business district did not amount to much: a forgettable stretch of uninspired wooden storefronts, indistinguishable from a thousand other hick towns languishing in the boondocks. In short, Nordhoff was homely. Libbey had a remedy. He had internalized the great lesson of Chicago, which was that art and human progress were inextricably linked. And among the arts, architecture was especially effective at creating a physical context for uplift. What had been true of Athens and Rome could become true of Nordhoff: Beautiful buildings would inspire civic virtue among the inhabitants, and make the town a better place in every sense. In April 1914, Libbey called a meeting of Nordoff’s leading citizens to offer a suggestion: They should essentially scrap the town they had, and build a new one.

“Make no little plans!” That was Daniel Burnham’s advice to the city planners of America, and it was Edward Libbey’s advice to the burghers of Nordhoff. His wildly ambitious proposal evidently stirred the blood of every man at that meeting, for they voted unanimously to embrace it. Why would they not, given that Libbey and his rich friends would provide most of the funds? And so the great experiment began.

There were still a few details to fill in. First and foremost, who would be Libbey’s architect, and what style would he employ? The choice ultimately fell upon Richard Requa of San Diego, whose firm, Mead and Requa, did some work for the Panama-California Exposition of 1915. Libbey evidently visited the San Diego fair, was impressed by its Spanish Colonial Revival motif, and hired Requa to create something similar in Nordhoff.

But the sequence of events suggests that Libbey already had settled on the Mission style for Nordhoff, well before he ever set foot in Balboa Park. After all, he had been familiar with the style at least since 1893, when he first clapped eyes on the California Building at the Chicago World’s Fair. And he no doubt had admired the Thacher School’s administration building, a Mission-style structure built in 1911. Significantly, the first major new building erected in Nordhoff in the immediate aftermath of that April 1914 meeting was a Mission-style movie theater, the Isis. (It’s still there, almost a century later, only now it’s called the Ojai Playhouse.) Given the town’s enthusiastic embrace of Libbey’s plan, it seems most unlikely that someone would have built a major new building in the downtown district without first vetting the design with the man from Toledo.

Libbey did have other architectural choices. The most impressive-looking building in downtown Nordhoff in 1914 was the Ojai State Bank, a stately brick pile in the neoclassical mode, complete with Doric columns. Theoretically, Libbey could have put up a neoclassical village to match the bank. But that would have looked bizarre, given the region’s historical context. The closest points of reference were Ventura and Santa Barbara, each of which dated back to the Mission Era and boasted an authentic mission building. Mission Revival was the obvious choice for Nordhoff. It seems likely that Libbey had made that decision even before he called that meeting.

Libbey of course was no architect. He left the design details to Requa, who used a mixture of Mission style (e.g., the Arcade) and Spanish Colonial Revival style (the Post Office Tower) to bring Libbey’s vision to life. Meanwhile, in March 1917, the town completed its Ramona makeover by changing its name to Ojai. Now it had a Spanish-sounding name to complement its new look. (The name, like the architecture, is not actually Spanish; it’s derived from the name of one of the Chumash Indian villages that once dotted the valley.) Thus it was Ojai Day, rather than Nordhoff Day, that the town celebrated a few weeks later on April 7.

At the opening ceremony, Libbey handed the deed to Civic Park to Sherman Day Thacher, who accepted it on behalf of the newly formed Ojai Civic Association. A reporter for The Ojai newspaper recorded Libbey’s speech, an earnest paean to the power of art:

“Art is but visualized idealism, and is expressed in all surroundings and conditions of society,” he told the crowd. “From the earliest age to the present time, art has been to the races of men one of the greatest incentives toward progress, refinement and the aesthetic missionary to the peoples of the world.”

Did the townspeople take Libbey seriously, with all his high-falutin’ rhetoric about Greece and Rome and beauty and virtue? Relatively few people in the crowd knew him well. He was only a part-time resident, after all. But clearly he was sincere, and most of his listeners were grateful that he had taken Ojai under his wing. Heads nodded in agreement as he launched into his peroration:

“Thus we are today celebrating, in the expression of this little example of Spanish architecture in Ojai Park, a culmination of an idea and the response to that spark of idealism which demands from us a resolution to cultivate, encourage and promote those things which go to make the beautiful in life, and bring to all happiness and pleasure.”

The crowd gave Libbey a huge ovation. And then the party began.

“Last Saturday a new epoch in the social and industrial life of the rejuvenated and resuscitated ancient Nordhoff, under a new title and new conditions, was ushered in and welcomed with joyous acclaim and much felicitation,” The Ojai reported in its next issue. “It was the most memorable day in the history of the Valley. New life, new ambitions and greater accomplishments will date from April 7, 1917.”

THE LIBBEY LEGACY

Ojai Day was not celebrated in 1918, due to America’s participation in World War I. But it returned in 1919 and became an annual event, as Libbey’s influence provided the town with more new buildings to celebrate: The St. Thomas Aquinas Chapel (now the Ojai Valley Museum) in 1918, the El Roblar Hotel (now the Oaks at Ojai) in 1920, the Ojai Valley School in 1923, the original Ojai Valley Inn clubhouse in 1924. Then Libbey died in 1925. The town continued to celebrate Ojai Day until at least 1928, but at some point after that, the tradition was abandoned.

The buildings, of course, remained. But as the decades passed, some of them fell into disrepair. The original Pergola was demolished in 1971, the same year Civic Park was renamed Libbey Park. “And we almost lost the Arcade in 1989,” Walker said.

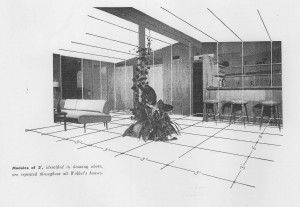

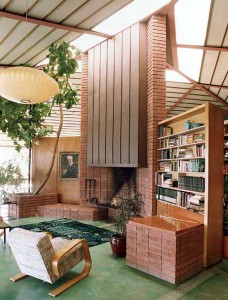

Walker is a retired Nordhoff High School history teacher and an expert on the valley’s architectural history. (He inherited some of that expertise from his late father, the noted architect and longtime Ojai resident Rodney Walker.) He was a member of the citizens group that saved the Arcade, by raising funds to refurbish it and bring it up to code. In the wake of that effort, Walker led a move to bring back Ojai Day. The event was revived in 1991, and now is celebrated each year on the third Saturday of October.

Walker also was among the people who brought back the Pergola in 1999. As a member of the Ojai Valley Museum board, he continues to lend his expertise to the museum’s projects. It was while researching a talk about Ojai architecture that Walker learned that Libbey had been an exhibitor at the World’s Columbian Exposition, where he would have been exposed to both the Mission Revival style and the City Beautiful Movement. Walker already was familiar with Libbey’s Ojai Day speech from 1917, but now he viewed those words in a new light.

“The words just echoed the real heart of what the City Beautiful Movement was all about,” Walker said. “On that day in 1917, the architectural and social ideals of the World’s Columbian Exposition were expressed in a beautiful new civic center that was created by a man who owed his own success in large part to that same Chicago exposition.”

Did Libbey achieve his dream for Ojai? Certainly his influence on the look of the town has been enormous. Walker points to all the beautiful Mission- or Spanish-style buildings that other people erected in the valley after Libbey worked his magic downtown. These include the Krotona Institute of Theosophy, Villanova Preparatory School, the Ojai Presbyterian Church, the Ojai Unified School District headquarters (formerly Ojai Elementary), the Chaparral Auditorium, and many, many others.

But an Ojai building need not be Mission style or Spanish style to reflect Libbey’s legacy; it need only be beautiful. Nor is his influence limited to architecture. Today the town is known as a mecca for artists, and Libbey, in a sense, was their prophet. He called for the community to pay more attention “to things aesthetic,” and his call has been heeded.

“It all goes to show, first of all, that one man can make a difference,” Walker said. “Libbey’s ideas must have infected the people of Ojai.”

In one way, Libbey outdid Daniel Burnham. The glorious White City burned down in 1894; only one of its buildings remains standing in Jackson Park. But Libbey’s buildings still stand along Ojai Avenue, and still perform their intended function. Burnham’s lost masterpiece was a blueprint for future cities that were never built, except, perhaps, by L. Frank Baum and Walt Disney. But the Emerald City is imaginary, and Disneyland is a theme park. Ojai is a real town, where people live. If today Ojai prides itself on its beauty and on its highly developed sense of civic virtue, then much of the credit must go to Edward Drummond Libbey, who set out to build a better town, and succeeded.

“I think it helped people realize that they live in someplace special,” Walker said. “This was Libbey’s stated intention “to inspire people to these higher ideals of civic involvement. One could say that his intention has been borne out.”

(Originally published in the Ojai Quarterly’s Fall 2012 issue. Republished with permission.)

(Originally published in the Ojai Quarterly’s Fall 2012 issue. Republished with permission.)

Shangri-la: Ojai’s Untold Stories, the final exhibit for 2012 at the Ojai Valley Museum, will run for three months, October through December 30, 2012. It features historical, primarily unknown personalities, who were directly related to Ojai and who have had great influence on the town and the nation. The five “Untold Stories” featured in this exhibit highlight the lives of Ethel Percy Andrus, Benedict Bantly, Edward Libbey, Effie May Skelton and Edward Jacob Wenig; all of whom were tenacious, passionate, political, fearless, selfless, and adventuresome movers and shakers in a wide variety of fields and endeavors.

This tour de force, original history exhibit is comprised of text and three-dimensional installation/tableaux chronicling the five personalities, plus six short stories about additional influential individuals and little known tidbits of Ojai history. The primary stories about the three men and two women, all of whom had ties to Ojai, serve to educate, enlighten, surprise and impress. Visitors will be enriched by the information within these stories and their awareness of this community will be greatly expanded.

The concept for this exhibit – to relate stories about Ojai that are not known by most people – was conceived several years ago. Four Community Curators, Patricia Atkinson, Laura Crary, David Mason and Craig Walker, researched and wrote the texts and gathered supportive ephemera for each individual/person featured in the exhibit. Michele Ellis Pracy, Ojai Valley Museum Director, curated each of their contributions to form the overall group exhibition.

Contributors to the Shangri-la exhibit include: AARP, The Gables of Ojai, Ojai Community Bank, Ojai Estate Sales, Treasures of Ojai, Jim McCarthy and Christine Brennan, La Piu Bella Tavola, Tony and Anne Thacher, Bob and Alyce Parsons, Christine Fenn, Veronica Cole, Ojai Valley Inn and Spa, Angelique LaCour, Teri Thomson Randall, Barbara and Sandy Service and Lily Liu.

The museum is located at 130 W. Ojai Avenue, Ojai, CA. Admission: free for current 2012 members, adults – $4.00, children 6-18 – $1.00 and children 5 and under free. Gallery hours are Tuesday – Saturday 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Sunday, noon to 4 p.m. Tours are available by appointment. Free parking is available off Blanche Street at back of museum.

The Ojai Valley Museum, established in 1967, is generously supported in part by Museum Members, Private Donors, Business Sponsors and Underwriters, the Smith-Hobson Foundation, Wood-Claeyssens Foundation, City of Ojai, Rotary Club of Ojai, and the Ojai Civic Association.

For more information, call the museum at (805) 640-1390, ext. 203, e-mail ojaimuseum@gmail.com or visit the museum website at: OjaiValleyMuseum.org

Wheeler Hot Springs: New Owners Confront Old Issues by Mark Lewis

From The Ojai Quarterly, Spring 2011 issue.

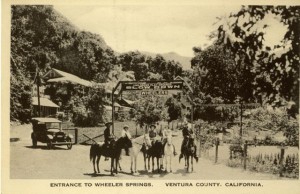

Most Ojai visitors arrive from the south on Highway 33 and turn right at the Y, heading toward the Arcade or the Ojai Valley Inn. But there was a time, not all that long ago, when many of these drivers would turn left instead, and smile gratefully at the highway marker proclaiming that Wheeler Hot Springs was only six miles away.

Most Ojai visitors arrive from the south on Highway 33 and turn right at the Y, heading toward the Arcade or the Ojai Valley Inn. But there was a time, not all that long ago, when many of these drivers would turn left instead, and smile gratefully at the highway marker proclaiming that Wheeler Hot Springs was only six miles away.

“It was almost a pilgrimage for me,” said Arthur von Wiesenberger, co-publisher of the Santa Barbara News-Press, as he recalled his regular Sunday trek over Casitas Pass and up the Maricopa Highway to take the waters at Wheeler. “I looked forward to Sunday,” he said. “There was a special energy there. I’d come back and face the week rejuvenated.”

Wheeler nostalgia is not confined to out-of-towners. Many local residents flocked to the resort to soak in its spring-fed hot tubs and enjoy a massage, followed by dinner and perhaps a jazz concert. “It was awesome when it was open,” recalled Jerry Kenton, co-owner of the Deer Lodge. “I used to go there on dates. It was great.”

When the resort closed in 1997, many people assumed that it would eventually reopen under new management. But a decade passed and nothing happened. Then, late in 2007, Wheeler began to show signs of life.

No announcement was made, but the resort had acquired new owners: Daniel Smith, a dentist who lives in Malibu and practices in Agoura Hills, and his wife, Maureen Monroe-Smith, who according to her Linked-In profile is an editorial assistant at Momtastic.com and the owner of Zuma Canyon Vineyards. For a while, to judge from the construction activity at the site, they seemed to be putting a lot of money into the place. But three-and-a-half years later, Wheeler has yet to reopen, and the new owners have yet to make their plans public.

“They try to keep it real private,” said Kenton, who co-owns a rental property right across the highway from Wheeler. “He [Smith] doesn’t want any publicity.”

The Kenton property is listed for sale with Sharon MaHarry of Keller Williams Realty, so MaHarry is often on the site. She said she never notices any activity at Wheeler, and has no idea what the Smiths have in mind.

“It’s a mystery to everybody in town,” she said.

Nevertheless, Smith was reasonably forthcoming when the Ojai Quarterly telephoned him last October to ask about his plans.

“We’ve been doing a tremendous amount of work to improve the property,” he said. “Unfortunately, the county has made it extremely difficult to re-open it.”

Smith said he would consider doing a sit-down interview on the Wheeler site. But when we got back to him a few weeks later to set it up, he asked us to hold off on our story.

“We’re at kind of a crucial point here,” he said. “At this stage, I don’t really think we want to put people on the property. What we’re doing is not really defined yet. We’re just not sure on direction yet.”

If the OQ would wait for a month, Smith said, he would tell us what was going on. So we waited more than a month, until January, and then we called him back. He did not return our calls.

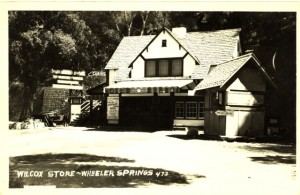

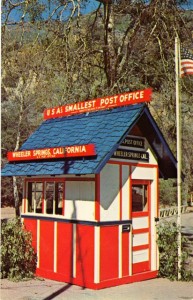

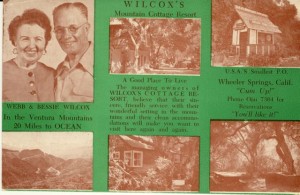

It seems that the Smiths have run into a bit of bad luck at Wheeler. (See below.) But they are hardly the resort’s first owners to find themselves in this predicament. For more than a century, Wheeler Hot Springs has been luring visionary developers into the Santa Ynez Mountains only to break their hearts. Yet Ojai would not be what it is today without Wheeler, and the other hot-springs resorts that once graced the area. Lanny Kaufer, whose family operated Wheeler on and off from 1969 through 1993, notes that the resort will continue to loom large in Ojai’s history, even if it never reopens.

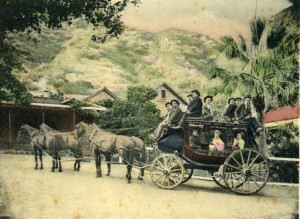

“The hot springs were the major draw that brought people to Ojai in the first place,” he said. “That’s what put Ojai on the map.”

Deer Hunter Discovery

The Chumash phrase for hot springs translates into English as “tears of the sun.” It is often assumed

in Ojai that the Wheeler hot springs were sacred to the Chumash, but this cannot be confirmed: No archeological evidence for the Indians’ presence at the site has turned up thus far, and Chumash elder Julie Tumamait-Stenslie knows of no ancestral stories about the springs that have been passed down to her generation.

“The stories were lost,” she said. “We don’t know of anything documented. You want to trace legends and lore, but I’ve always come up to a dead end.”