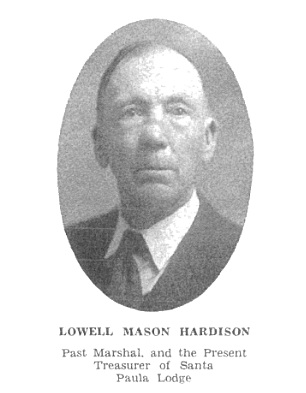

The [Upper] Ojai Valley by Lowell Mason Hardison

Lowell Mason Hardison was an early settler in the Upper Ojai Valley. He was born in Caribou, Maine, on August 25, 1852. Mr. Hardison was a businessman in Caribou for a number of years; he also served as deputy sheriff and town treasurer. Later, he went to Pennsylvania where he was employed in the oil business. He moved to Santa Paula in 1883, where he became a successful rancher.

Lowell Mason Hardison was an early settler in the Upper Ojai Valley. He was born in Caribou, Maine, on August 25, 1852. Mr. Hardison was a businessman in Caribou for a number of years; he also served as deputy sheriff and town treasurer. Later, he went to Pennsylvania where he was employed in the oil business. He moved to Santa Paula in 1883, where he became a successful rancher.

Lowell Hardison’s cousin was the well-known Santa Paula oilman Wallace Hardison, who founded the Union Oil Company with Thomas Bard and Lyman Stewart.

What follows is a paper written by Lowell Hardison on the early history of the Upper Ojai Valley. The paper was donated to the Ojai Valley Museum by Ojai resident Terry Hill.

*****************

I have been requested to write something of a historical nature for the Pioneer Section of the Ebell Club of Santa Paula. The history of the pioneering of California and Ventura County has been well written by persons more competent than I. What can I write that will be of interest to you who are making a study of this subject? The days of the pioneers have past. Why did people leave the East to come to this country of deserts, privations, and hardships? I will answer for myself as an example.

My first recollections of hearing the name California was when I was about eight years of age. Father and another man were telling about what befell a man who went to California a few years before. They knew his folks.

Just over the boundary line that separates the State of Maine from New Brunswick is a section of country they call California. I have been told that it was so called because so many of its menfolks had gone to that state during the mining excitement of 1849. The hardy men of Maine and the British provinces were the kind of material for pioneers to go into a new country and subdue it in spite of the obstacles of nature placed as barriers to impede their progress; such as great mountain ranges, vast expanses of barren desert without food or water, harassed by roving bands of hostile Indians, and bad white men that stole their cattle and horses.

It was about one of a party of those who had left California, New Brunswick, for California, U.S.A., that I heard the harrowing story that I shall always remember. This man they were telling about had heard the stories told about the atrocities the Indians inflicted on captives. He said, “I am not afraid of Indians. I am going to shoot the first one I see.” He did. The next morning their wagon train was surrounded by a large number of Indians in war paint who demanded the man who did the shooting be given up for punishment. Being so greatly outnumbered, they complied in order to save the lives of the entire party. The Indians tied him up and commenced at his toes and skinned him alive, while the others had to look on.

From that time, for several years, like most boys who had any ambition, I had daydreams of going to California to mine for gold and fight Indians. I read many books written about California such as Richard Dana’s “Two Years Before the Mast”, Fremont and Kit Carson stories, and the Oregon trail. The time came when I had to make a change of climate, as my health was such that I could not stand the cold winters of Maine. We decided to go to California, the land of my early dreams.

On my arrival in California, I met many people who came here during the gold rush period and had followed mining for many years since. At Placerita Canyon, a few miles above Newhall, I met a man who came around Cape Horn in the second ship that General Veazyie sent out from Bangor, Maine, for California. He knew my nearest neighbor who was to have sailed on the same ship with him, but owing to sickness, was left behind. This man, Mr. Drinkwater, showed me how to pan for placer gold. I bought a miner’s pan and a horn spoon for an outfit. As soon as I got settled and was able to do so, I prospected in the gulches on the south side of San Cayetano and Topa Topa mountains. I had not yet learned that it was not of much use to look for gold in sandstone formation.

I had heard the tales told by old timers of the lost Padre and of other mines, and had seen old long-whiskered miners settle their store bills at Scotts or Cohens by pouring fine gold out of buzzard quills onto small balances that nearly every trader kept for that purpose.

In prospecting I saw many strange things. On the east side of the Ireland (or Harvey) Canyon a short distance below where it leaves the wooded glen was a small Indian burial ground. It had headstones and was covered by a dense growth of brush. Dr. Stephen Bowers who had made extensive researches in archeology for the National Museum said it was the only case he had found where they buried their dead in asphalt.

The [Upper] Ojai Valley and the mountains on either side, as late as when I came here, were a hunter’s paradise. I was told by a man that was one of the party hunting with Thomas R. Bard, when he first came to the country, that they camped one night on the creek not far from the Santa Paula sulphur springs, they were disturbed in their slumbers by a grizzly bear turning Mr. Bard over with his paw. They yelled so loudly that the bear left in a hurry. They surmised that the bear found that he had disturbed a new specie of animal that he had better leave alone. Wild hogs were quite plentiful. Their tracks could be seen the road nearly every day. They were very wild and swift of foot. Hunters did not bother them as they took to the thick brush at the slightest noise. No dog could drive them out. The flesh of the wild hog is strong and oily. They produce no lard. George Bay captured several small pigs one summer and fed them on grain. The flesh was too strong for white men to eat. One large boar was monarch of the Sulphur Mountain; he would clean up a pack of dogs in short order. The nimrods and mighty hunters gave him a wide berth. Rabbits, quail, doves, and wild pigeons in the winter time were plentiful; trout abounded in the streams that emptied into the Santa Paula Creek.

But few people know of the fertile soil, fine scenery, or delightful climate of this section of our county. I lived in it for many years and had great faith that it would be discovered sometime by real estate agents, divided into small holdings, and sold to those able to build fine homes and develop the land so it would become a paradise. I believe it has the best climate of any country for elderly people in which to spend their declining years. Mr. M. C. Harvey has shown what hard work can do. He has transformed a rough canyon into a place of beauty and delight. If the ghost of the departed Indians should ever return that once roamed over the hills, they would think they had found the happy hunting ground and put up a stiff fight against being thrown out.

About halfway up the Sisar Canyon, well up on the side, I discovered an old road that, by its width, must have been used as a wagon road. It was several hundred feet in length and covered with a heavy growth of brush. I thought that it must lead to one of those lost mines. I searched for several days to find the beginning or the end of the road without success. I learned later that some of the timbers used in building the od Mission at Ventura were brought down this canyon. On the west side near the mouth, I found an old camping ground, or should I say a picnic ground, for by the shells that I uncovered, it must have been a meeting place for a clambake. Some of the shells were very old, no doubt, but the creek ran much higher on the bank than it does now, and flowed through the Ojai Valley. We have the old channels of creeks as evidence. In blasting out a large boulder, I found underneath a fine mortar-pestle, which I think you will find in the archives of this Society. On the Gibson and Bracking places, evidence of large Indian campgrounds could be traced; many stone implements were uncovered in plowing the fields. In the side of the bank of an old creek bed, on land that I once owned, was a cave high enough for a man to stand up in, and large enough to house quite a family. I think the occupants must have left in a hurry and had no time to remove their household furniture, as all was broken. Perhaps it was a tribe of Matilija Indians that wiped out the Indians of the upper Ojai Valley. Who knows?

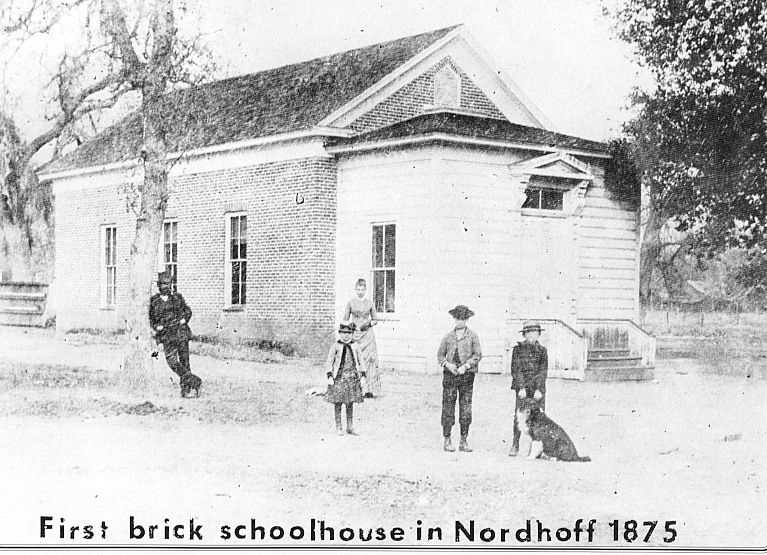

As a reminder to you of the flight of time, I will try to record the names of the people who owned places between the Blanchard and Bradley Mill, and the head of the grade to Ojai, or Nordhoff as it was called at that time (as far as I can remember):

First, Harrison Crumrine, rancher and schoolteacher.

Sam Todd, a friend in the time of trouble. He lived alone after his mother passed away. The place is well known as the Say place.

Washington Rhodes, orchard and bees. He always stayed drunk as long as the east wind blew. He sold out to W.L. Hardison, now owned by J.N. Proctor.

Julio Peralto, Lectra Briggs place. He was quite extensively engaged in the cattle business. He had a large family.

John Mears, a native of Ireland. He had several large bands of sheep. The place is now owned by the Harveys.

George Smith, a one-armed Englishman. He came around the Horn. He was born not far from the Tower of London. (Place now owned by Anlauf.)

Alex Farrell lived at the foot of the Deitz Hill. He kept bees and had a few lime trees. Limes were a luxury at that time.

Skaggs, now owned by Doheny. The gate is well guarded; no trespassing is allowed.

Above the Skaggs place on the Santa Paula Creek, Alexander bee man.

Fred Richardson above No. 6 oil well.

Newcomb J. Ireland, at the mouth of the Ireland canyon, a millwright and bee man. Came here from Kansas.

George Bay, the first place on top of the hill at upper Ojai. He did some farming and kept bees. Place now owned by oil company.

The next place west, Joe Specht, farmer, born at sea of German parents. Place now owned by Davy.

James Bracking, farmer and wine maker. His farm was used as a camp ground for many Indians indicated by the marks left. He was born near the River Shannon in Ireland within sight of an old Roman fort. The place is now owned by the oil company.

The next west is Thomas Gray and sisters. They are still on the place.

John Thompson, farm and orchard, native of Ireland; now the Tucker place.

Thomas Clark, farming and wine making.

Robert Gibson, farming, cattle and horses, a native of Scotland, who came around the Horn with his family in a sailing vessel, was killed by being thrown out of a spring wagon by a runaway team.

John Pinkerson, farming a fruit, came from the North of Ireland. Al Drown now owns the place. [Pinkerton was one of the first in upper Ojai to buy land from Thomas Bard.]

Next west, Proctor, and Englishman. Tom McGuire is the present owner.

Captain Robinson, farmer, native of Maine. Place now owned by Barnard.

Joseph Hobard, farming, fruit and cattle, native of Massachusetts. He was one of the Vigilantes that ran the gamblers and bad men out of San Francisco in 1856. The place now owned by M.H. Butcher.

Henry Dennison, farmer and horticulturist. He said that his ______ took a prominent part in rounding up Napoleion Bonaparte after he had overran nearly all of Europe. His sons own the place.

I believe that the Dennisons and the Grays are the only ones left in the [upper] Ojai Valley of the original settlers who live on the same farm they did in 1883.

Wishing happiness and long lives to the people of the Ojai Valley, that beautiful land of sunshine, I will close

L.M. Hardison

October 1, 1936