Dr. Ethel Percy Andrus a talk given to the Ojai Valley Museum by Craig Walker on May 1, 2011

Ethel Percy Andrus founded Grey Gables of Ojai, the National Retired Teachers Association, and the American Association for Retired Persons (AARP).

Perhaps you’ve seen the new AARP television commercial. It’s hard to miss if you watch CNN. The commercial opens with an interior shot of a dimly-lit farm structure; the narrator speaks:

“A chicken coop; the unlikely birthplace of a fundamental idea. It’s where Ethel Percy Andrus found a retired teacher living because she could afford nothing else. Ethel couldn’t ignore the clear need for health and financial security…and it inspired her to found AARP.”

Ethel Andrus founded AARP on the simple premise that no one should have to live in a chicken coop, that all Americans-including the elderly–should live independent, productive, and dignified lives.

What the commercial doesn’t mention is that Ethel Percy Andrus founded AARP while living here in Ojai. For several years, she ran AARP from her offices at Grey Gables–another one of her innovative ideas. Grey Gables of Ojai, established by Andrus in 1954, was one of America’s first retirement communities.

What the commercial doesn’t mention is that Ethel Percy Andrus founded AARP while living here in Ojai. For several years, she ran AARP from her offices at Grey Gables–another one of her innovative ideas. Grey Gables of Ojai, established by Andrus in 1954, was one of America’s first retirement communities.

Ethel Percy Andrus believed strongly in the power of numbers. All of her organizational efforts were guided by three principles: collective purpose, collective voice, and collective purchasing power. By the time she died in 1967, AARP had grown to 1.2 million members. Today, AARP (now headquartered in Washington DC) has over 40 million members; it is the second largest membership organization in America after the Catholic Church. AARP magazine (which Ethel created, and edited for many years) has three times the circulation of any other American magazine-with over 35 million readers! Because of these numbers, AARP has become one of the most powerful research, advocacy, and consumer organizations in America!

But Ethel Andrus did so much more than just create an organization! Through her tireless efforts, she changed the lives of America’s senior citizens and, more importantly, she changed the way society views retirement and aging. If your life has not already benefited from the work of Ethel Percy Andrus…it will!

Ethel Andrus also believed in the power of years. She believed the elderly are uniquely qualified by their longevity and their retirement to bring meaningful change to society. She exemplified this through her own life. Ethel founded the National Retired Teachers Association when she was 63; she moved to Ojai and founded Grey Gables when she was 70;…and she founded AARP when she was 74! After that, she went on numerous speaking tours, wrote countless editorials, met with presidents, and lobbied Congress and state legislatures. All of this…came after retiring from a distinguished 40-year career in education! …In 1993 Ethel Andrus was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame–alongside her mentor, Jane Addams, and many other important American women like Susan B. Anthony, Helen Keller, and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Certainly, Ethel Percy Andrus qualifies as one of Ojai’s most accomplished, influential, and famous residents! She was a social reformer and civil rights leader of national importance, who did much of her significant work here in Ojai. And yet, her name is seldom mentioned in listings of important Ojai residents. Nor is it widely known that Ojai is the birthplace of AARP–an organization that has improved the lives of so many Americans. This talk is an attempt to correct these oversights-and to pay tribute to a truly remarkable woman!

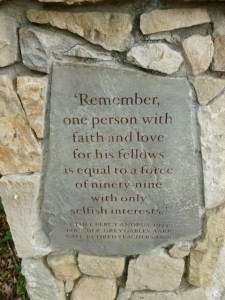

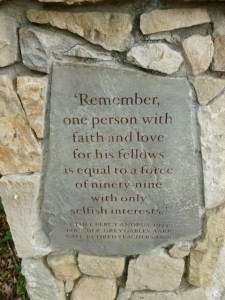

Ethel Percy Andrus was born in San Francisco in 1884, but grew up in Chicago. She decided at an early age to dedicate her life to serving others. She credits her father for that decision; he taught her that everyone should do good somewhere in the world, and that the greatest rewards in life come when one serves others. Ethel’s personal motto was “To Serve, Not to Be Served,” which is still the motto of AARP.

In 1903, at the age of 18, she earned her bachelors degree from the University of Chicago and began teaching English at the Lewis Institute.

During Ethel’s years teaching in Chicago–from 1903 to 1910-she volunteered at Hull House, a “settlement house” founded by Jane Addams to help low-income European immigrants living on Chicago’s east side. In a settlement house, social workers live in the community, learning first hand the needs of the residents while providing them with educational, medical, and counseling services. Ethel’s work with Jane Addams at Hull House would lay the foundation for her future work as a high school principal, and her later work improving the lives of America’s senior citizens.

In 1910, Ethel and her family moved back to California because of her father’s poor health. Ethel’s first teaching job in California was at Santa Paula High School. In 1916 she was offered an assistant principal position at Lincoln High School in Los Angeles. When the principal quit the following year, Ethel was given the job. This made Ethel Percy Andrus the first woman principal of a large, urban high school in California! She would serve in that position for the next 28 years.

At the time, East Los Angeles High School was a large school with one of the highest dropout and juvenile delinquency rates in the country. Like Hull House, it was located in an area populated by poor immigrants, representing a range of races and ethnicities. Ethel took on the challenge–not just of teaching subjects–but of transforming lives.

As an English teacher, Ethel Andrus knew the power of words, and so she used words to instill dignity and hope into her students and their families. She built a gateway into the school, with a single word written in large, wrought iron letters overhead: “Opportunity”. Every student, as they entered the school, was reminded that education was an opportunity for them to better their lives and the lives of others.

“In an age of hard-nosed, gruff male principals,” reported the Los Angeles Times, “[Ethel Andrus] might have passed for Marian the Librarian. She was a red-haired, bespectacled, soft-spoken educator… whose success came from building close relationships with both teachers and students. A former teacher once said of her: ‘When you spent time with Ethel, you felt you’d had a drink of strong, heady wine.’ Single and childless, Ethel served as a mother figure to many of her students and a friend to others. She once said, ‘I never met a child who couldn’t embrace me.’ She treated pupils with firmness and affection that produced extraordinary results.” One unruly student reported years later, “Somehow…you found yourself acting the way she wanted you to!” (Los Angeles Times, Dec. 14, 2003)

Another former student, the actor Robert Preston, recalled: “The big iron scroll on the Abraham Lincoln High School gate through which we passed read: ‘Opportunity’. Isn’t it amazing that we didn’t know until we walked out: Opportunity had red hair!”

Ethel Andrus taught her students to take pride in their family heritage. Her goal was [quote] “to bring each student a sense of his own worth by treating him with dignity and respect, by honoring his racial background not as a picturesque oddity, but as a valued contribution in the tapestry of American life.” She instituted school activities that built leadership skills while breaking down cultural barriers. She established a program of community service that instilled self-esteem and confidence through service to others. As a result, the school’s delinquency and drop-out rates fell dramatically. The Los Angeles County Juvenile Court awarded Andrus and her school a special award for success in youth crime prevention. In 1940, the National Education Association published her programs as a model for other schools to follow in reducing delinquency and racial/ethnic conflict.

Andrus’ efforts to improve the lives of her students didn’t stop at the school gate; she worked to improve the community as well. Ethel was responsible for renaming the neighborhood “Lincoln Heights” and its park, “Lincoln Park”. Working with business leaders, she established Lincoln High School as a community center that reached out to immigrant families through their children. She started an Opportunity School for Adults, which raised the educational level and English skills of parents and other adults living in the neighborhood.

To set an example, Ethel went back to school herself, furthering her own knowledge as an educator. In 1930 she received her doctorate from the University of Southern California–one of the first women to do so. She then taught education classes at UCLA, USC, and Stanford during summer vacations-inspiring a whole generation of future teachers. Not only was she the first woman high school principal in California, she helped found the California Association of Secondary School Administrators and served as its first woman president.

In 1944-after 40 years in education with 28 years as principal of Lincoln High School-Ethel Andrus retired to care for her ill mother. She was 60 years old. Had she done nothing further in life, she would still be remembered as a noted educator and humanitarian. But Ethel’s mother inspired her to take up the cause of others in her retirement. “You thought your work was done when you gave up youngsters,” her mother told her, “but it’s only the beginning.” How true that would turn out to be!

Ethel volunteered with the Southern Section of the California Retired Teachers Association. She was given the position of Director of Welfare, which monitored the living conditions of retired teachers. Ethel took an interest in this because, when she retired as a principal, she discovered her pension was only $60 a month! Although she had money of her own, she found it hard to believe that a retired teacher could survive on just $60 a month!

One day she was talking with a local grocer near Los Angeles. He asked if she would check on an old woman he hadn’t seen for several days; he gave Ethel the woman’s address. The people who lived there didn’t recognize the name, but then said, “Oh, you must mean the old woman living out back.” That’s when Ethel found a former teacher living in a chicken coop. The woman was gravely ill, but had no money to visit a doctor. It was a moment that would change the life of Ethel Percy Andrus–and the lives of America’s elderly. Ethel was known for rarely expressing anger, but whenever she told that story-even years later–she could barely control herself. It angered her that society would allow retired teachers to live like that…and she decided to do something about it

The first thing she did was to organize retired teachers on a national level. In 1947 she founded the National Retired Teachers Association, with the goal of [in her words] “putting dignity back into the life of the penniless former teacher.” Ethel Andrus’ vision for retired teachers was captured in three words: independence, dignity, and purpose. One of her first projects as NRTA President was to find an insurance company that would offer medical insurance to NRTA members. In 1947 most jobs had a mandatory retirement age of 65, and it was virtually impossible for retirees to purchase health coverage; Medicare would not be established for another 18 years. Ethel hoped that with a large, national organization, she could secure a group policy. Yet, even with 20,000 members (and growing), she was turned down by over 40 insurance companies. The elderly, she was told, were uninsurable. As an alternative, Andrus decided to create a chain of 15 NRTA-sponsored retirement communities that would include medical and nursing home care. She began raising funds and started searching for a location to establish the first one–which would serve as the prototype for the others.

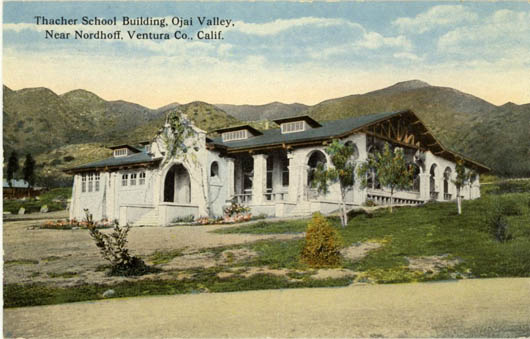

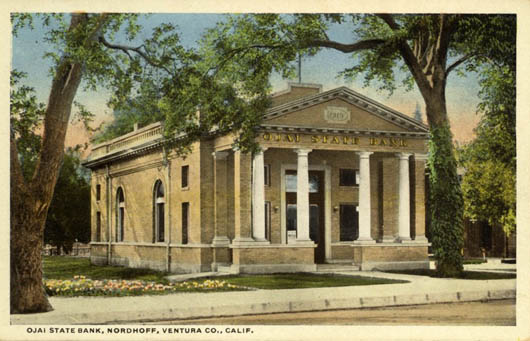

In 1953 she was on a speaking tour of California schools; after her talk she would ask each faculty member to contribute $2 toward the retirement home fund. One stop was Nordhoff High School here in Ojai. The morning after her presentation she spied a large, three-story house for sale on the corner of Montgomery and Grand; already named “Grey Gables”, it had several small apartments, common living areas, a library, and a large music hall. It even boasted Ojai’s first elevator! The former owner had designed it as a cultural center and a boarding house for working teachers.

Ethel Andrus applied to buy Grey Gables, which would serve both as a model retirement community and the NRTA’s headquarters. The Ojai city council at first refused to approve her “retirement home”. (We can only guess what images arose in their minds when they heard the words “retirement home”.) But Ethel Andrus, with her natural charisma and her soft-spoken but firm manner, persuaded the Council, and they reluctantly approved the project. Like the unruly boys at Lincoln High School, “somehow”…they found themselves acting the way she wanted them to!

Ethel Andrus applied to buy Grey Gables, which would serve both as a model retirement community and the NRTA’s headquarters. The Ojai city council at first refused to approve her “retirement home”. (We can only guess what images arose in their minds when they heard the words “retirement home”.) But Ethel Andrus, with her natural charisma and her soft-spoken but firm manner, persuaded the Council, and they reluctantly approved the project. Like the unruly boys at Lincoln High School, “somehow”…they found themselves acting the way she wanted them to!

At first, Grey Gables was just the large, three-story house along Montgomery Street north of Grand. In 1954, she purchased Sycamore Lodge, a motel next to Grey Gables that fronted Grand Avenue; later, several apartments were added on the back and west side of the property. The Acacias nursing home was built in 1959. Early residents of Grey Gables were attracted by Ethel’s vision of an active life of service, and so the Gables soon became an important asset to the community. Its residents served on local boards, tutored in the schools, taught classes at the Art Center, and volunteered throughout the valley. In 1959 the Ojai city council-which had originally balked at the project-awarded Ethel Andrus and her Grey Gables residents a city proclamation honoring their many contributions to the community

At the 1964 New York World’s Fair, the NRTA exhibit featured a large, 3-dimensional model of Grey Gables; it was promoted as the future of retirement living in America. With its attractive buildings, lush gardens, swimming pool, travel programs, on-site medical facilities, and volunteer opportunities within the local community, Grey Gables became a model for future retirement homes across America.

A small house next to Grey Gables served as the headquarters for the NRTA. Ethel Andrus asked several former colleagues to move to Ojai to serve on the NRTA Board and help run the organization. One such person was Ed Wenig, who had been the drama teacher at Lincoln High School. Ed became one of Ojai’s first historians, and was instrumental in stopping the freeway into the valley.

In 1956, two years after founding Grey Gables, Ethel Andrus finally located an insurance broker who would write health policies for NRTA members. That man was Leonard Davis, a small-time insurance broker from Poughkeepsie, New York. Just as Ethel predicted, membership in NRTA multiplied as retired teachers, desperate for health insurance, joined the NRTA. The new NRTA Health Plan was a huge success!

It wasn’t long, however, before Ethel began hearing from other retirees, begging her to create a plan for them.

In 1958, Ethel met with Leonard Davis and her Ojai attorney-Jack Fay-at the Ojai Valley Inn. Over dinner they outlined a new organization that would represent-and insure-any retiree 65 years of age or over. Later that year, Jack Fay filed incorporation papers for the American Association of Retired Persons. At 74, Ethel was now president of two national organizations–and Director of Grey Gables. In addition, she started a magazine for AARP-Modern Maturity-which she both published and edited; her spirited editorials soon became the voice of America’s seniors. With a small staff, she ran both national organizations from her offices at Grey Gables in Ojai.

In 1963, when AARP and NRTA reached a combined membership of over 400,000 members, Ethel moved their administrative offices to Long Beach, but kept the membership operations in Ojai. From 1963 until 1967, she divided her time between Ojai and Long Beach. Of course, much of her work involved traveling to Washington DC and various state capitals to advocate for the elderly. For all this she took no pay.

Her partner, Leonard Davis, formed his own insurance company, Colonial Penn, which offered low-cost health insurance to all AARP members. Needless to say, his association with AARP turned into a goldmine. After paying AARP a royalty for each policy sold, Leonard Davis and Colonial Penn reaped huge profits. At one point Davis appeared in Forbes’ list of the 400 wealthiest Americans. But, Ethel Percy Andrus’ spirit of selfless service and giving must have affected him, too, for he became one of America’s great philanthropists. One of his projects was to expand Ethel’s work in researching the needs and capabilities of the elderly. In 1973 he established the Ethel Percy Andrus Gerontology Research Center at USC. Today, it is the oldest and largest gerontology research center in America.

While Ethel Andrus was AARP president, the organization began offering many other important benefits to its members: She set up a mail-order discount prescription drug service; she pioneered the concept of senior group travel; she negotiated discounts for AARP members at restaurants, hotels, and car rental businesses. (So popular were these discounts that now most businesses offer senior discounts regardless of AARP membership!) In 1963 she founded the Institute for Lifelong Learning to provide classes and seminars focused on the interests and needs of retired persons. She also turned AARP into a nationwide volunteer organization…today, over 168,000 AARP volunteers assist seniors with tax preparation, teach computer skills, instruct driving refresher courses, and much more.

Although AARP is non-partisan, and doesn’t support political campaigns, it has a powerful presence in Washington DC and the state capitals. It lobbies on issues that are important to older Americans–and is supported in its lobbying efforts by its large membership base; nearly one in five voters are AARP members! During her years as leader and spokesperson for AARP, Ethel Andrus scored many important legislative victories. She helped pass Medicare and Medicaid; she also improved Social Security, secured tax benefits for seniors, instituted cost-of-living increases for pensions, outlawed mandatory retirement, and ended discrimination against the elderly. These are all things we take for granted today, but they were not easy victories at the time.

For all of her success in building two national organizations, Ethel Percy Andrus’ most important achievement was in changing America’s image of retirement.

“As it is,” Ethel observed in 1958, “when you leave a job, they often just give you a gold watch, and all you can do is look at it and count the hours until you die. Yet think of all the grand things we can do that youth can’t. Think of all the things we already have done. Someday, the retired citizens of this country will have the dignity they deserve.”

In numerous editorials and speeches Ethel Andrus promoted retirement as the beginning of one’s creative life–not the end of it. “Creative energy is ageless,” she would say; it is focusing on ourselves and our own problems that defeats us. Retirement is an opportunity to move beyond ourselves by serving the needs of others and, in so doing, be fulfilled as human beings. She urged seniors, “Retire, not from–but to service!

Through her dedicated efforts, Ethel Andrus brought millions of retirees out of their isolation and back into the mainstream of American life. She encouraged these retirees to find part-time jobs, go back to school, travel, get involved, and most of all to volunteer in their communities. She built a gateway over the entrance to retirement and framed it with a single word: “Opportunity”.

When Ethel Percy Andrus died in 1967, she was interred in a small garden at Ivy Lawn Cemetery in Ventura; one of many eulogies was written by the President of the United States, Lyndon Johnson:

“The life of each citizen who seeks relentlessly to serve the national good is a most precious asset to this land. And the loss of such a citizen is a loss shared by every American. In Ethel Percy Andrus, humanity had a trusted and untiring friend. She has left us all poorer by her death. But by her enduring accomplishments, she has enriched not only us, but all succeeding generations of Americans.”

Those of us who grew up in Ojai during the 50s and 60s probably rode our bikes by Grey Gables several times a week. Little did we know that inside a team of elderly retirees, led by an 80 year-old dynamo, was quietly revolutionizing retirement in America. Little did we know that their accomplishments would give us the opportunity to live the independent, productive, and dignified retirement Ethel Percy Andrus envisioned over 60 years ago. Little did we know… “Opportunity had red hair!”

Those of us who grew up in Ojai during the 50s and 60s probably rode our bikes by Grey Gables several times a week. Little did we know that inside a team of elderly retirees, led by an 80 year-old dynamo, was quietly revolutionizing retirement in America. Little did we know that their accomplishments would give us the opportunity to live the independent, productive, and dignified retirement Ethel Percy Andrus envisioned over 60 years ago. Little did we know… “Opportunity had red hair!”

For a more detailed history of Dr. Andrus and AARP, read “The Age of Reformation: Dr. Ethel Percy Andrus and the Founding of AARP” on this site.

The above is an excerpt from Ojai: A Postcard History, by Richard Hoye, Tom Moore, Craig Walker, and available at Ojai Valley Museum or at Amazon.com.

The above is an excerpt from Ojai: A Postcard History, by Richard Hoye, Tom Moore, Craig Walker, and available at Ojai Valley Museum or at Amazon.com.