Note: This article was written by Emily Thacher Ayala and first appeared in Edible Ojai, No. 22, Fall 2007. It has been slightly modified and contains additional photographs.

Murky Water

Until the desert knows

That Water grows

His sand suffice

But let him once suspect

That Caspian fact

Sahara dies.

Emily Dickenson, No. 1291

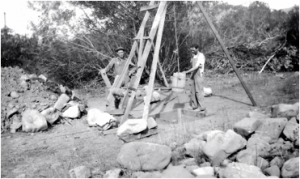

We do live in a desert—ok, that’s a bit of exaggeration used by many writers about Southern California–but when my great-grandfathers arrived here, one from England and the other from New England, they found a far different place in the Ojai Valley than what they had left behind. The sage and sumac embedded in dry rocky ground, the oak woodlands with their grasses and burr clover that had literally saved the Hispanic bovine bacon for more than a century. There was no water from the sky for most of the year and all too briefly there could be too much. My great-grandfather, Sherman Thacher, in his first year upon arrival and working at his older brother’s fledgling orange orchard on the east end Grand Avenue wrote to his mother in New Haven, Connecticut that, “Edward planted and God refused to water.” Irrigation water had to be hauled by barrel to the thirsty trees before dams, ditches, flumes and furrows were constructed over the next few decades. Indeed, irrigation was by far the most time-consuming and constant portion of the early farmers’ labors. From the other side of my Ojai roots, my grandfather, Elmer Friend, always said about his spring, summer and fall efforts of constructing and maintaining the thirsty furrows that he had “moved every rock in the Ojai Valley at least twice,” a bit of hyperbole I never heard any of his contemporaries deny him. Look at those massive stone walls in the East End and you also may begin to believe. And, of course, thanks to their efforts our valley is now a far different place that they have left as a legacy to us to labor in and enjoy ourselves.

But the subject of water seems to be at the forefront again… or perhaps the lack thereof and the price we must pay for it. Growing up I was acutely aware of water. Sometimes there was too much, with mud and boulders growling in the river below our orchard, but most times too little to maintain our special swimming hole in the Ventura River. I remember having to share bathwater with my brother, even with my parents. It was rather murky water–the water coming from the spring above our house, gravity fed directly into the pipes with whatever fine plant life and dirt the spring and pipes contained, then into the tub to be mixed with the daily grime of two grubby farm kids. It’s no wonder I’m not squeamish about the cleanliness of my fingernails. I remember times when water would not reach the upstairs bathroom during the summer; there just wasn’t enough pressure in the pipes for it to get there, teasing me from my upstairs bedroom by hovering in its tubular home in the wall between me and the ground. During our last sustained drought there wasn’t much water in the spring which might trickle only at night when the willows and other canyon plants demands were at their diurnal low.

Our spring-fed house would also do without water when a flood or fire came along damaging the system. Sometimes the pipes simply came apart from wildlife or our dogs mucking about in the spring. Someone (usually my dad) would go up the canyon amid the willows and poison oak and fix the pipe and clean the screen filter. Then in the 90’s we had a well drilled, and a tank put in, which has solved lots of our domestic water issues. When the pump is on, the tank is filled, and even if the spring runs low we have enough water to take showers; most of the time. Like any power outage, being our own ‘water company’ is a good reminder to be thankful for the utilities that others work long and hard to provide us with.

Attached to our water system for the house is the water system for the orchard. This system starts with a whole slew of larger pipes; one from the spring, from the well, the water tank and from the river. The orchard is divided into blocks each with a main valve connected to the various sources of water. Blocks are further divided into rows with a line of hose and their own riser and valve from the pipe below. Irrigating the orchard is tricky, determining which source of water to be used in each block, balancing the water to flow where it needs to go, ensuring that the sprinklers have enough pressure on the sloping ground. You turn on the water for a block and make sure the pressure gauge stays between 25 and 35 psi. If the pressure isn’t high enough, then turn off rows of sprinklers until the pressure is sufficient. When water is plentiful it takes 3 days to irrigate the whole 20 acres, 2 blocks each day. On a dry year when the spring is trickling and the well not pumping at full capacity it takes 5 days or more, and during some of those days you won’t take a shower upstairs. It’s tricky business, one must take into account the slope of the land—make sure the top of the slope is getting sufficient water. You don’t want to shortchange the trees at the end of the line. And of course make sure some water still flows to the house; don’t leave Mom with soap in her hair. And remember not to close too many valves or you may blow up a pipe—.

We all made mistakes—I’ve blown up a few water lines in my ignorance of where the pipes lie underground and what valve to open or close and in what order. I’ve also turned the well on to fill the tank and forgotten to close the valve after filling the tank; sending water gushing out onto the ground. We do have a one-way valve installed coming from the spring, so you can’t pump water back into the spring, which would certainly surprise the other critters using the spring. Yet this back flow of water might loosen the murk in the pipeline!

This may seem like a convoluted system for providing water to a mere 20 acres and one home, but I can assure you it isn’t much different on other local farms that balance water storage and use from various sources. Nor is it different from the larger daunting task that our local water companies undertake daily. Our Ojai Valley water comes from wells, Lake Casitas (CMWD), springs and then flows to storage tanks, balancing reservoirs, and directly to users. Getting that water around to each home and orchard involves an enormous number of valves, pumps, pressure gauges, miles of pipeline and lots of human vigilance! The water companies have a lot of people to answer to if the water stops or the pressure isn’t sufficient to reach someone’s upstairs. Water companies can’t get away with only allowing us to have water several days a week while they repair something or scratch their collective heads about a problem as we can with our orchard. Just to add to the task, water companies must have their water squeaky clean–minimal murk is not allowed under state drinking water standards. Add to the tasks for our water companies that much of the infrastructure they are using was put in place many years ago and virtually all of it is underground. It’s not surprising that they need to raise their rates to maintain the systems and have budgetary concerns during wet years and times of drought conservation. Farms may use more water, and we are willing to pay the cost of the water delivered, but the infrastructure and administrative costs should be shared equally among all customers who are able to access the system. This should include meters that only use water when their other sources become unavailable. This seems only reasonable to us.

Farmers are much more in tune with our water history, the delivery systems, and how they function, than the average residential customer. We are not opposed to paying for water as it sustains our industry. We are opposed to unfair and drastic rate changes that could potentially put us out of business. I suspect that with this recent rate change some folks that have small farms (5 to 10 acres around their home) may simply shut off the water and call it quits after they receive their water bills this fall and make the comparison to their income from growing oranges. As orchards go dry and are removed the feel of our valley will change. If you are curious to know what a fallow orchard looks like, check out the corner on Fordyce road where an orchard was removed several years ago. Or the empty field on the north side of Grand avenue between Carne and Fordyce. I live on Fordyce and can attest to the fact that the only benefit of these fallow lands is an influx of ground squirrels, some lizards, a few birds and lots of dust. If the valley reverts to sagebrush and the dust increases, our Ojai will become a less desirable place to live. Water keeps our valley green and pretty, provides jobs and food, and a buffer from wildfires. We should keep the orchards green for those reasons alone.

I’m not sure where we are headed with costly water rates. As the price rises we use less, the water companies sell less and then need to increase rates to make up for the lost income. We need to start acting as if we have a finite amount of water from all the sources available and price it out to all users in an equitable manner. Conserve, conserve—turn off the water when brushing your teeth, only flush for when necessary, don’t over water your yards, etc. Heck, you can even share bath water with someone— let’s ensure there’s enough to go around. Lastly, please do rain dances or say a special prayer in hopes that the heavens open to give us ample rainfall this winter!

When the well’s dry

We know the worth of water.

Benjamin Franklin,

Poor Richard’s Almanac