In Ojai, Issues and Causes Didn’t Change by David Mason

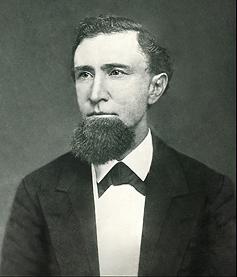

‘The Ojai’ is for sale. When I came to the Ojai I had but $68. In four years I have accumulated more property than most men can show for a lifetime of labor; I can still show more than $1,000 a year profit from the paper. It will therefore be seen that ‘The Ojai’ is perhaps as well-paying a business as any in this town, and that it will be a good investment for whomsoever shall purchase it.

Editor and Proprietor Randolph R. Freeman The Ojai, 1900

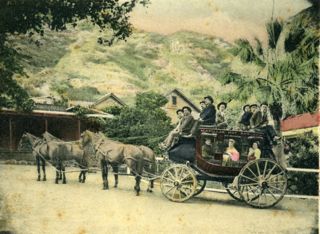

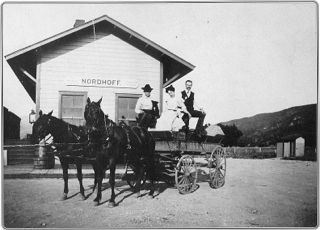

The changing of the dates from the 1800s to the 1900s was hardly celebrated by the people of the small western town of Nordhoff, now Ojai. The editor of the local newspaper, The Ojai, chose this time to make a decision to leave this “wild west” town. Not quite being “run out of town,” but close, the editor said, “Within four years, assaults with intent to kill me have been three in number, all unprovoked, and I have had some lovely fist-fights. I have never said anything in the paper concerning them – because my adversaries have themselves had no paper of their own, and it would hardly be fair; and perhaps but few of my readers know even by hearsay of these little affairs. However, the blow which I received on the head this week has shattered my nerves to the extent of incapacitating me for work. Nor have I yet recovered the strength which I lost by my recent siege of typhoid fever; I fear it shall be a long time before I am returned to my wanted health on account of this combination of causes. Therefore, I must quit the newspaper business for a time at least.”

The beginning of the year 1900 would bring the all-important farm report to the front page of the local paper. “The farmer of the past century has been of the pioneer order. His work in the main was to clear new lands, get new homes in shape and begin the work of farming scientifically.” Predictions for the coming years included: “The ideal American farmer of 1900 will have an entirely different mission to fill. It will be necessary for him to be more energetic than the old times for he will have much stronger competition to meet. His stock will be pure-bred and of high quality, and it will be fed systematically, with a mind well-cultivated and everything carried on in a business way, he will move along subjugating nature, and by invention, machinery and fertilizers will double the products of his land and thus be ready to reap a full share of benefits arising from the advance of American civilization and American commerce.”

From the music industry and the Choir Musical Journal for 1900, the main subject was the insane craze for

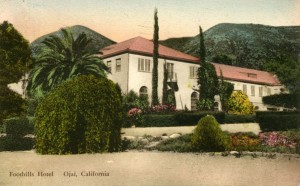

“ragtime” music. “The counters of the music stores are loaded with this virulent poison which, in the form of a malicious epidemic, is finding its way into the homes and brains of the youth to such an extent as to arouse one’s suspicions of their sanity. The pools of slush through which the composers of some of these songs have dragged their questionable rimes are rank enough to stifle the nostrils of decency, and yet young men and ladies of the best standing daily roll around their tongues in gluttonous delight of the most nauseating twaddle about ‘hot town’ and ‘warm babies’ – some of them set to double-jointed, jumping-jack air that fairly twists the ears of an educated musician from their anchorage. Some of these songs are so maudlin in sentiment and rhythm as to make the themes they express fairly stagger in the drunkenness of their exaggerations. They are a plague to both music and musicians, and a stench to refinement.” With the new year dawning, the sports world would also make the news, the Ojai Tennis Tournament Committee began work on building the new tennis courts in the back of the Ojai Inn, now Libbey Park. “The ground has been plowed and leveled. One-third of the backstop posts have also been erected. The work of sifting the surface earth will begin next week.” The tournament for 1900 was held on Friday and Saturday, April 6 and 7.

The game of golf was also popular in 1900. Statistics for the year found that there were 200,000 golf players in the United States, using 3,200,000 clubs, the cost of which, including breakages and repairs, bring the total spent up to $8,000,000. It would have taken 1,000 freight cars loaded to capacity to have carried them. The balls used added up to 2,400,000-dozen per year, a mere trifling expenditure of $8,400,000 annually. Dues paid on the various golf clubs amounted to $6,000,000. With so much spent on the game, The Ojai newspaper felt that it should really be considered “the national game.”

The “homeless” were also a big news item. The Ojai Valley was working to deal with the problem of tramps. “The whole country is still confronted with the tramp problem. It costs California scores of thousands of dollars each year to pay officers’ costs for arresting, jailing and feeding for a few days these roving men.” The paper reported that had the governor signed the “Tramp Bill,” these men would have been at work, either on the highways or the county farm. The people felt that the whole problem would have been solved, the state would have saved an immense expense, the roads would have been greatly improved and the people would not have to put up with the annoyance of the tramps begging for money.

The Ojai editor wrote: “The tramp is a human being; he is our brother no matter how ragged, degraded or demoralized he may be. He may lack energy; he may have bad habits; he may be badly balanced; he may himself be to blame for his destitute condition, but he is human and must be so treated. Don’t curse the poor tramp. Some men are born financiers, others are not. When a man’s last dollar is gone and he has no bed in which to sleep; no money with which to buy food, and his toes are out of his shoes; his clothes are ragged and dirty, he loses his confidence, he easily becomes demoralized and discouraged, and life is shorn of its charms. Let the state take hold of this problem, and solve it; it can be done. Safety to the community requires it. Religions demands it.” In the entertainment news, the local paper reported that: “A band of Italian gypsies in wagons and rags passed through Nordhoff on Thursday. The head man of the outfit had a trick bear which danced and wrestled $2.60 worth, to the great delight of the population, while his Indian wife with a papoose led a little monkey around by a string and caused it to dance and do tricks whenever 10 cents was proffered. The whole gang begged food and clothes to the tune of several barley-sacks full and went on their way rejoicing.” The editor couldn’t help but add some advice to travelers with, “If the gang were but half so dirty they could easily dispense with one-half the horses now required to haul them about.”

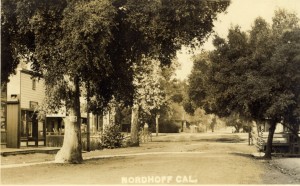

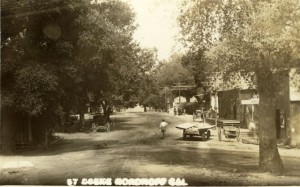

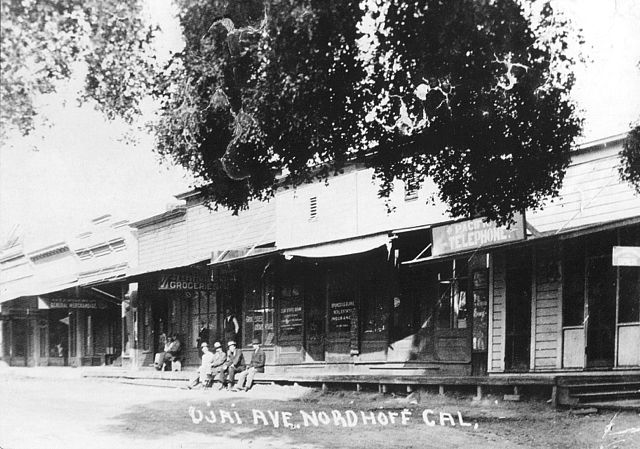

The turn of the century brought about major water issues, too. The Santa Barbara News said: “What’s the matter with having a few watering troughs in the city? The water company have disconnected the ones on Canon Perdido and Haley streets. What’s the matter with the city reconnecting them?” The Los Angeles Express, commented by using the town of Nordhoff as an example: “Whatever difficulty exists between the water company and the city of Santa Barbara is non-essential to the point in hand. The plan of providing watering troughs is one which should be immediately put into execution, and these should be placed at frequent intervals along the highways. If Santa Barbara officials are in doubt to the good effects of this scheme, let them drive over the mountains to the little village of Nordhoff, in the Ojai Valley. There on the principal street, and heavily shaded by one of those grand old live oak trees which have made the Ojai famous, is a big, generous trough brimful of the most delicious mountain water. Such public improvements are an index to a town’s character, and will be jotted down by the visitor seeking for a place to locate.”

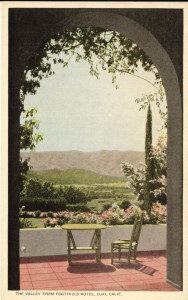

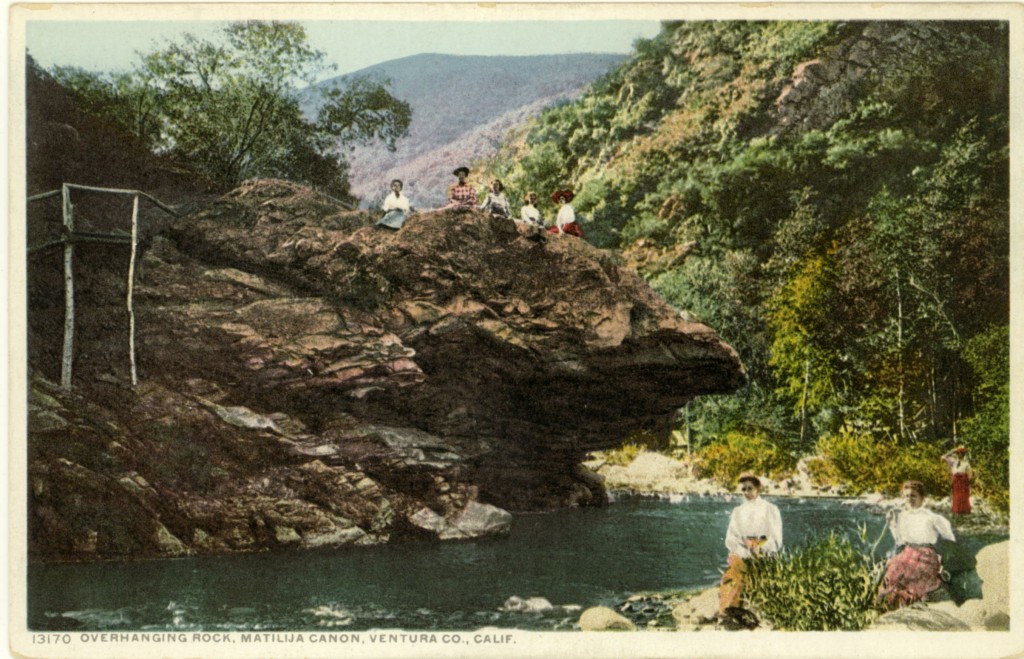

For a segment on travel and leisure, the trees in the valley were being written about in the Honolulu-Bulletin. In regards to the trees growing in their streets, the editor wrote: “If a precedent for the tree’s occupancy of part of the thoroughfare is required, allow me to refer to the village of Nordhoff, in Ventura County, California. Nordhoff has a very warm summer climate, which has naturally caused the people to prize their fine oak shade trees. The village is built under the trees, which are allowed to stand wherever they chanced to grow. If they are in the street, the people drive around them, saying the trees were there first and shall not be molested. How grateful the shade of those trees is to man and beast can be understood when the love of the people for the trees is known. In California the protects the trees in the roads or streets; and, in Ventura County in particular, woe to the man who lays his ax to any tree upon a public road. There the trees as well as the people are protected, and if an overhanging limb gets too familiar with passersby, an order from the supervisor of the district must be obtained before the offending part of the tree can be removed.”

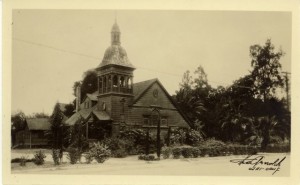

The new year’s news, from the local Presbyterian Church was very exciting; a special offering was taken on Sunday amounting to $58.30, which was more than double any previous basket collection. In the building category, “A number of enterprising citizens are engaged today in a fence-building bee. They are enclosing the Presbyterian Church lot. Cows shall hereafter keep off the grass, the posies and the plants.” “The trustees and patrons of the George Thacher Memorial Library (now Ojai Library) extended the ladies and gentlemen of the Ojai Valley their sincere thanks for the praiseworthy efforts in the dramatic line which brought into the treasury of the library, eighty dollars to be expended for books.” A very successful library fund-raising event for the beginning of the 1900s. A lot of changes took place in the Ojai Valley during the last 100 years, but did we really change that much? A very happy and successful new year to each and everyone of you.

“Now get up a little rally

And come to the Ojai Valley,

You dear friends back there,

With snow and ice in your hair,

Come enjoy winters fair.

Orchards loaded with golden fruit,

Which is sure to suit,

And it’s plain to be seen,

That nothing grows lean,

With hills and dells all green.

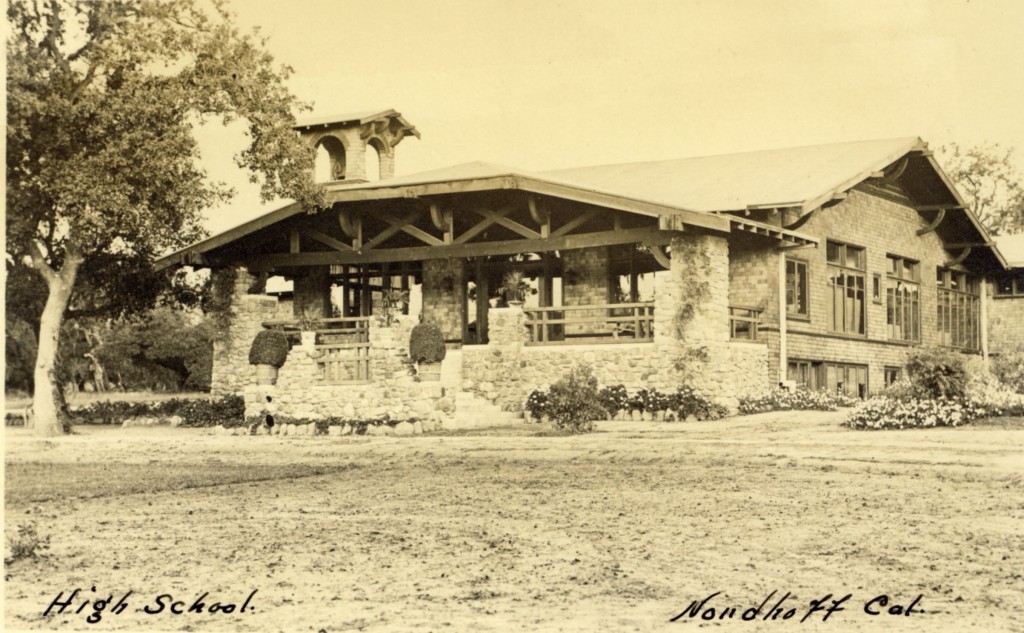

Our schools are the best

To be found in the west;

Teachers and scholars all

Both great and small,

Can answer the call.

Our several preachers

Are all good teachers;

They tell us that we must,

In God put our trust,

Then the devil we can bust.

In this valley so fair

Is the home of many a millionaire,

But now please remind,

That they are the generous kind,

Which you seldom find.

Now hurry with your rally,

On high, to this beautiful valley,

For it’s sure some treat,

And it can’t be beat.”

O.I. Bill, 1900