Long before James Hilton published Lost Horizon (1933) and Frank Capra produced his film on the same subject (1937), The Ojai, that mystical harmonious valley enclosed by majestic mountains and fed by tumbling streams, was regarded as Shangri-la by those in search of wealth, health, spirituality or any mixture of the three. And therein lies the problem: what constitutes an earthly paradise for some demands stasis; for others, “forward movement” which always involves friction.

Consider the earliest days of The Ojai and its Garden of Eden reputation. Why wouldn’t residents and health seekers alike wish to preserve an atmosphere that guaranteed relative immortality in a world being decimated by phthisis, wasting disease, graveyard cough, acute, galloping, or military consumption? In the 1800s and early 1900s, fully one-fifth of the world’s population was dying of what we today identify as tuberculosis. Theories for medical cures abounded. All were unpalatable; none were effective, and some were deadly: arsenic, atropine, strychnine, calcium, gold, mercury, colloidal preparations of silver, copper, aluminum and silver, boa constrictor excreta, blistering, fresh blood (hopefully but not always from animals), pig-spleen extracts as well as an inhalation of the breath of healthy animals or the effluvium of maggoty meat.

By the early 1900s, antiseptic or hot air inhalations emptied as many hospital wards as death itself as patients fled from the painful treatment. The in-hospital cure rate: a meager and likely inflated three to five per cent.

The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 brought brilliantly colored posters trumpeting “Go West and Breath Again.” New York Evening Post editor Charles Nordhoff’s California for Health Pleasure and Residence (1873) not only brought throngs seeking all three to the country’s 31st and most romanticized state, but also gave the name of its author to the village on the valley floor in 1874. By the 1890s, The Ojai set its claim into print with its masthead: “For the Good of Mankind, by Telling of the Greatest Sanitarium for Throat and Lung Troubles in the Known World” “The Famous Ojai Valley.”

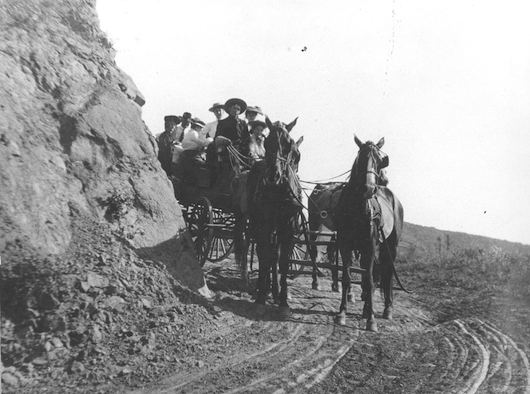

Alice B. Chase, of Lynn, Massachusetts, was afflicted with a lung weakness that brought her and her unmarried daughter, Alice P. Chase, to The Ojai for the first time in January of 1904. The winters of Lynn, located 10 miles northeast of Boston, were dreary snowfall was excessive; the cold, piercing. In 1912, Mrs. Chase was to recall that first trip, when writing to Alice Barnett Clark, married to Ojai stagecoach driver Bob Clark, in 1905:

I well remember when we first saw Nordhoff and Bob gave us our first drive and picked so many flowers and gave Miss Chase her first riding lesson (Cal. style). By the time this reaches you, you ought to have some flowers for we came to Nordhoff on January 6th I think and the next day we found over 40 varieties of flowers and Bob was able to name them all. Oh, it was so beautiful, and what is best the beauty comes back again every year. (1/01/1912)

At the other end of the spectrum, the Clark family had emigrated from famine-stricken Ireland in 1855. Tom Clark, Bob’s uncle, was drawn to the gold fields of California “Oh, Mary, there’s gold there, now never you mind” finally settling down to farming in Sonoma County. In 1868, however, Clark read of The Ojai in one of the 5,000 handbills distributed by T. R. Bard in the San Francisco Bay area, advertising land at $3 to $5 an acre in the Upper Ojai; $9 an acre in the Lower. (Bard kept the mineral rights for his employer, T.A. Scott, railroad magnate and Lincoln’s former Assistant Secretary of War.) Bard’s crew first cut a rough road from the Lower to the Upper Ojai, hand-drilled wells into the side of the magnificent Sulphur Mountain in search of the crude so valued then and ever since.

Most who purchased his parcels of surface land sought to improve it to accommodate their more basic needs. It was those who “improved” the land, however, who provided the amenities allowing the wealthy of fragile health to come to the valley. The Chases, for example, spent their winters at the luxurious steam-heated three-story Foothills Hotel, completed in 1903, “a station of the world’s great highway,” where “men and women talk of Nice, and Paris, and Vienna, and Hongkong [sic] and Honolulu as mere stopping places on the road, the while they drink in the view and are glad that the Ojai was made for the delectation of the happy.” (Sheridan, Sol N., “Ventura County, California.” Sunset Magazine Homeseekers’ Bureau: San Francisco, California, 1908.)

By the time Tom Clark was interviewed by historian Yda Addis Storke in the 1880s, he had acquired 180 acres of land in the Upper Ojai, “making the wilderness to bloom like the rose. … He has erected a comfortable home and has one of the finest ranches in the valley, raising Morgan horses, Poland China and Berkshire hogs and Jersey cattle. Mr. Clark also has a splendid vineyard and makes his own wine, a superb article.” Ms. Storke further admired the fruit orchard, rose garden and Clark’s extensive wheat fields.

The article closes with an anecdote told by Clark of a visiting minister, “Mr. Clark, I must congratulate you,” stated the reverend gentleman. “The Lord has placed you in a fine vineyard.” “Yes,” said Clark, “but the Lord had nothing but brush and stones here when I first came.” For Clark, Shangri-la was opportunity, his dreams realized after years of hard labor: taming the land and dealing with the grizzlies that passed with ease through his fences.

Blacksmith Lorenzo Dow Roberts, an old-time Democrat, was forced to leave North Carolina because of his outspoken abolitionist beliefs. He then emigrated from his new home in Bloomington, Illinois in search of a cure for his chronic “bronchitis.” When he first arrived in The Ojai, he could speak only in a hoarse whisper, wrote Signal editor W.E. Shepherd, in 1873. “Now, he can yell so as to be heard a mile.” With his newfound energy (he had gained 44 pounds in his 11 months in the valley), Roberts attempted the first subdivision of the lower valley, which he named “Ojai.”

Although his proposed subdivision for the village failed while that of the more aggressive valley booster, Royce Surdam, materialized, Roberts, the invalid, continued his smithing and carriage making. Roberts thrived in his Grand Avenue “hospitable cottage with white picket fence, almost hidden from view by huge pepper trees and other ornamental shrubs,” enjoying his Shangri-la to the age of 73, while Royce Surdam, who had won the contest of the founding of the village, passed away at age 56 from an overdose of morphine.

One man’s bad luck became another’s opportunity in our Shangri-la. Around 1870, William and Mary McKee, having recovered their health in the Upper Ojai, decided to build Oak Glen Cottages on the corner of Ojai Avenue and Gridley Road as a sanitarium for invalids. J. N. Jones took in up to ten boarders at his ranch house in the East end; neighbor John Carne converted part of his 27-room room Victorian house into the Bonito House Hotel.

By 1887, miracles were happening in the 104-degree waters of the Ojai Hot Springs, located about eight miles above the village: Abram Blumberg claimed his “village for the sick” could cure not only lung ailments, but rheumatism, catarrh, erysipelas, dyspepsia, chronic diarrhea, sore eyes, liver and kidney complaints, cancer, syphilis as well as other blood and skin disorders. The waters of sodium, potassium and magnesium carbonates and sulphates, silicates, carbonic anhydride and sulphureted hydrogen also had a reputation for whitening and softening the skin.

“Nordhoff,” stated Mrs. Storke, “contains some 300 inhabitants, many of whom are recuperated invalids from nearly every State in the Union.” Ten years later, the local newspaper would complain “The Ojai is becoming too well known as a health resort for the general good of the valley. There are times when consumptives are quite numerous on the streets, some of them barely able to walk two or three blocks at a time.”

For Mrs. Chase and daughter, Shangri-la would ever remain The Ojai as they found it in 1904: Creek Road with its meandering crossings of San Antonio Creek, lined by massive live oaks dripping wild grapes, the majestic Valley oaks lining or intercepting the dirt roadways of the valley; the soft balmy air; the myriad flowers on the trail up to the Spring on Sulphur Mountain; the Pink Moment on the face of the Topa Topas. The valley’s isolation was a large part of its attraction, “off the beaten path, the path littered with the perpetually anxious in the crowded cities of the Eastern seaboard” but that same isolation proved a problem for its year-round residents.

The solution: bridges across the roaring torrents of the Ventura River, San Antonio Creek and Coyote Creek, which had claimed the lives of more than one valley resident during the wintertime deluges. “No, No, No,” said Mrs. Chase the time the first bridge was proposed, remembering at a later date: “Bob will remember how we protested against BRIDGES!!” (10/25/16)

Edward Drummond Libbey’s enlightened proposal for the ramshackle village, the one-block-long hodge-podge of haphazard buildings with false fronts of uneven heights, was also met with dismay from the ladies of Lynn:

Your description of Nordhoff is very interesting & welcome. We had heard something of the changes through the Ojai but like to hear first-hand. So you and Bob really like the transformation? We are so conservative we hate to have the charming simplicity of the place changed. (10/25/1916)

As conservative as the ladies Chase, Margaret Clark Hunt, too, found many of the changes in The Ojai difficult to countenance “particularly the highway from Ojai into Matilija over Pine Mountain through the Cuyama and the Maricopa into the great San Joaquin Valley” as proposed by her brother, Supervisor Tom Clark. The route through her beloved back country, her haven from the congestion that infiltrated The Ojai with each increase in population, was also the favored destination of her winter clients and her pupils at The Thacher School.

The highway did indeed bring about change, beneficial for the inland farmers, but detrimental to the peace of the valley and disastrous for backcountry’s once-supreme isolation. (These days, locals mourn the passage of the increasing numbers of gravel trucks rumbling down that same highway).

Ironically, Tom’s 30-year-old son, Jack, was killed on Feb. 2, 1936 by a dynamite explosion while working on the highway his father was so instrumental in building. “He was blown to bits,” reported cousin Alfred Reimer. “All that was left of him were his testicles, hanging from the branch of an oak tree.”

In a desert, water is king and The Ojai was first classified as a highland desert, with humidity ranging from 20 percent to 40 percent. With the increase in population, water provided by an average of 15 to 17 inches of rain per year, snowfall in the surrounding mountains and artesian wells proved inadequate to the demand. Typhoid fever from contaminated water was killing 50 area residents a year, two victims being Alice and Bob Clark’s 4-year-old daughter, Alice, or “Sweetsie,” her mother’s shadow, and 18-month-old George Patrick. Shotgun-toting farmers stayed up all night guarding their personal reservoirs from water rustlers.

Something needed to be done. And the Bureau of Reclamation came up with a plan: to build two dams, one in the Matilija Canyon, the second across Coyote Creek.

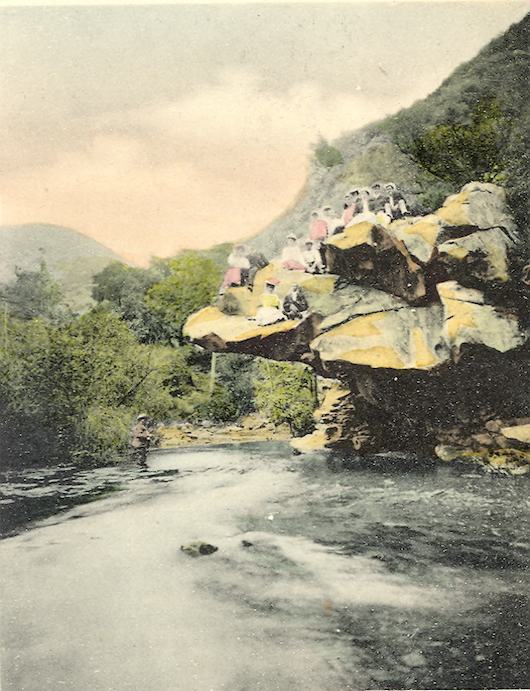

The Matilija Dam, completed in 1948, buried some of Ojai’s most magnificent sites: Twin Falls and the stately Hanging Rock, favored Kodak moment spot for tourists where Bob Clark proposed to the frail Alice Barnett in 1905. By 1952, just four short years after completion, Matilija Dam, now filled with silt and sediment, became obsolete.

Ventura County had begun to buy land for the second dam as early as 1947; construction was begun in 1957; the dam was completed in 1959 “a triumph for water supply in The Ojai” as well as the City of Ventura and the Rincon beaches westward to the Santa Barbara county line.

For Katherine Hoffman Haley, great-granddaughter of W. D. Hobson, considered by many to be the father of Ventura County, Shangri-la began with her family’s move to the 8,000-acre Rancho Casitas. Casitas grew to be one of the largest thoroughbred breeding ranches west of the Mississippi “almost by accident”.

Her father, brought from New Orleans by the Oxnard Sugar Beet Company, first raised Percheron horses on the ranch, then rescued a thoroughbred suffering from toothache. Hoffman cured the toothache and Crystal Pennant, in gratitude, won the $110,000 purse at Tijuana, the richest race in the world at that time. The sport of kings became the sport of Rancho Casitas, with every member of the family thriving in the exciting atmosphere and their nine-room, nine-bath Spanish-style home complete with barroom, music room and ballroom.

With the Casitas Dam project, the government claimed half of the estate, including the palatial Wallace Neff-designed home, which was razed to the ground. Kay’s new home, built on land she was able to retain, she named Rancho Mi Solar, home of my ancestors. Significantly, she made her statement with that home, built on a high point of land, of necessity adjacent to the lake, but positioned so that she need never again cast eyes on “that despised body of water.”

Kay made the most of her life thereafter, tending her shorthorn cattle and quarter horses, amassing an amazing collection of Western art and an equally impressive collection of awards recognizing her involvement in and generosity to the community.

Lester Peirano’s 240-acre Rancho Valenada, (Spanish for worth nothing), just up the road from Casitas Ranch, had been entrusted to him by his father when his two brothers, Nick and Vic, were given provenance over the grocery story across from the Mission in downtown Ventura. Lester failed at raising cattle as he couldn’t bring himself to castrate young bulls, dehorning was a problem as well.

He did beautifully, however, at raising peaches, melons, apples, pears, and, best of all, 55 acres of old country grapes, all sold at Peirano’s Grocery. Lester constructed his own Shangri-la from his father’s legacy. During the week, he held court under the “Whispering Tree,” at the corner of the vineyard, supplied with folding chairs and Teagarden jelly glasses regularly filled from the dripping water faucet nearby. Dust was no problem as the dirt was hard as concrete from the near-constant streams of tobacco juice supplied by Lester and his guests. The high point of the week for the shy farmer was Sunday, when his ranch became the gathering place for the entire family and legions of friends. (His mother and sisters organized the day.) When the county claimed his ranch, it broke his heart.

“And then one day an agent of the county did appear

It was the middle of harvest time and ’48 the year

And the solemn words he spoke then struck that farmer dumb with fear

So he spoke again for he was sure that Lester did not hear.“You see this country is a growin’ one and the county getting’ dry;

We must look toward the future now and that’s the reason why

A dam must be constructed where your fruit trees grow so high

We’ll see you get a fair price for the land that we must buy. “

The 11-stanza poem, unsigned, but recovered from the Peirano papers in 1994 when the last of the family died in Darby, Montana, continues:

“When they took his home Lester built a shack in the hills above the lake

On the land the county’d set aside to give him a new stake;

But the dream was gone and the days were long and at night he’d lie awake,

Thinking about his cherished land that he just could not forsake.”

The 40-acre piece of “land they’d set aside” was then claimed by the government for the Teague Memorial Watershed. Lester and Nick fought the government on this one and, after a two-year battle, did win a heftier sum of money — but only lifetime interest in the piece of land. It could no longer be considered a “family” ranch. The poem concludes with a flourish more heartfelt than accurate:

“It was on a cold and rainy day in the Fall of ’84,

That they found old Lester’s weathered coat and hat upon the shore,

And a simple note pinned to the brim shook the county to the core:

‘Forgive me, I just had to see and walk my land once more.'”

Rancho Chismahoo was another claimed by the lake, another gathering place for extended family and friends. The Bill Clark family departed for Northern California when a large portion of “the most beautiful ranch in the county” disappeared under the waters of Casitas.

Clark’s mother, Alice, one more pilgrim in search of health, came first to Los Angeles, then to The Ojai, where she met and married the previously mentioned stage driver Bob Clark in 1905, bore 10 children, and lived to the age of 73. She stipulated in her will that her two children, lost to typhoid fever in 1915, be re-interred with her.

From approximately 50 residents in 1873, the population of the village grew to 300 in 1891; to 8,046 in the village and a valley-wide population of 34,000 by 2005, the population inflated each year by entrepreneurs, health seekers, artisans and artists, followers of the great Krishnamurti, Meher Baba and other vendors of enlightenment. More pilgrims considered the East-West configuration of the valley conducive to occult and psychic forces and, eventually, as reported by Jack Brown in 1985, our population included “food faddists, occultists, the beard and sandal set writers, actors, yoga enthusiasts, radicals, conservatives, mystics, musicians, dancers, eccentrics, etc., etc.” “A mixture that at times strains the limits of civilized discourse” and Jack Brown never even heard of nude roller-skater/bicyclist Earth-Friend Gen, our most recent source of controversy in the Ojai.

The dry and invigorating breezes which drew early immigrants to The Ojai are no longer, with relative humidity now averaging a high of 95 percent thanks to the dams, irrigated orchards, vineyards, golf courses, lawns and other accoutrements of civilization. However, the citizens of our valley have successfully fought to keep the air clean through the years, blocking a university on Taylor Ranch at the mouth of the Ventura River corridor in the 1980s; and a dump proposed for the La Cañada side of Sulphur Mountain during the same period.

The grizzlies are long gone and the gentle black bear risks his life if he ventures close to town. We mourn our losses, large or small: the once-vigorous and highly prized population of ocean-going steelhead trout knocked in half first by the Matilija Dam and finished off by the Casitas Dam; the Evergreen Cattages, replaced by 2-story condominiums; and, most recently, The Ojai Frosty, a dilapidated but beloved gathering place.

Lerie Bjornstedt remembers with fondness buying decorations from Village Florist David Mason’s 50 Christmas trees; Maxine Tempske would like to see the return of Roth’s Sweet Shop and Soda Fountain, with its homemade candies of all kinds, and great ice cream sodas; Lavonne Theriault remembers when the “Y” was a cow pasture, just as I remember driving our cattle down the side of Sulphur Mountain, through Hall’s domain, across Creek Road to pasture on the McCormick place, now Saddle Mountain.

The most substantial change on the horizon today: the end of agriculture in The Ojai Valley, flourishing here since the 1870s, this change precipitated by Casitas Water District rate increases of 53 percent in 2007 and 19 percent in 2008. Pixie farmer Jim Churchill says his bill “to water 17 acres has soared 187 percent in two years.”

Farmers will have no option, says old-timer Tony Thacher, but to sink wells to replace Casitas Water. “This is the real danger to the Ojai Valley and our livelihood” a contentious and perhaps litigious situation that pits neighbor against neighbor as the water table sinks beneath our feet.”

Some would like to see a return to the Ojai of the highland desert, dryland farming, cattle raising and 20 percent to 40 percent humidity. Not likely. “If those trees die, and the land is left vacant, the days will come when the politics of development will overcome this valley, despite local laws to preserve farmland and open space. What we would have then,” continues actor/farmer Peter Strauss, “is not Shangri-la, but Sherman Oaks.”

Those who are best positioned to profit from this eventuality: the speculator, despised from earliest days of The Ojai. As stated in the Signal, January 1874, “We do not desire to see a wild spirit of speculation developed here,” [Speculation] is simply an underhand way of getting something for nothing.” And that something is what/where/why and how we live.

But, as philosophers and poets, scientists and sociologists from the time of Heraclitus tell us: “Change alone is unchanging.” The answer, says Mexican poet Octavio Paz, is simple, but not easy: “Wisdom lies neither in fixity nor in change, but in the dialectic between the two.” Even though we have no lamasery to guide us, if there is anyplace in the world where dialectic, or its near cousin, debate, flourishes, it is right here in The Ojai Valley, our own Shangri-la.

Yes, we are a contentious lot, each taken with his own vision of what The Ojai is or should be, and so it shall remain. Our debates are neither pointless nor are they inconsequential. To borrow from Irish poet, Patrick Kavanagh:

Homer’s ghost comes whispering to my mind

He says: I made the Iliad from such local rows.

Great story, Ojai will always be a healing place. Even before the 1800s, the indians would use hot springs for healing.

My father, Harold Clyde Mashburn, was born on Aug. 28, 1925 in a hospital in Ventura, California. He lived most of his entire life in the Ojai Valley, but was born in Ventura because Ojai lacked a hospital. Dad told me that he used to swim at Hanging Rock when he was a boy. I recall him describing to me the rock overhang. Dad was about 23 years old when Hanging Rock was demolished and Matilija Lake Dam was constructed in its place. Here’s some more Mashburn Family trivia: I began my career as a Park Ranger with the Ventura County Parks Department on Aug. 26, 1974 when I was 23 years old. I was assigned to be the live-on-site Park Ranger at Matilija Lake Park. I lived in the Park Ranger residence that was located in one of the park’s two campgrounds which were located on the banks of Matilija Creek up canyon from the dam and lake. On Feb. 10, 1978 it was raining cats and dogs! Matilija Creek was a raging torrent which eroded an earthen levy which allowed the swift running river to escape its banks. It surrounded the Park Ranger residence at 12:10 AM. I barely escaped with my life. The river swept away the residence and ruined the park. The campgrounds had old oak groves that were there during the days of native Americans. The flooding swept away most all of the oldest of the oaks. The County decided not to rebuild the park. Therefore, I was the last Park Ranger ever stationed at Matilija Lake.

Great story on Ojai!

Im grateful for the blog post.Much thanks again. Cool.

samsung galaxy s2 symbol for excellence

Do you have any stories to share about upper Ojai’s sulphur springs.

I own a home that was a resort with 11 cabins , a dance hall and a swimming pool. There was a bar across the street from us called the hind out .